Photography by Ishika Mohan Motwane

Photography by Ishika Mohan Motwane

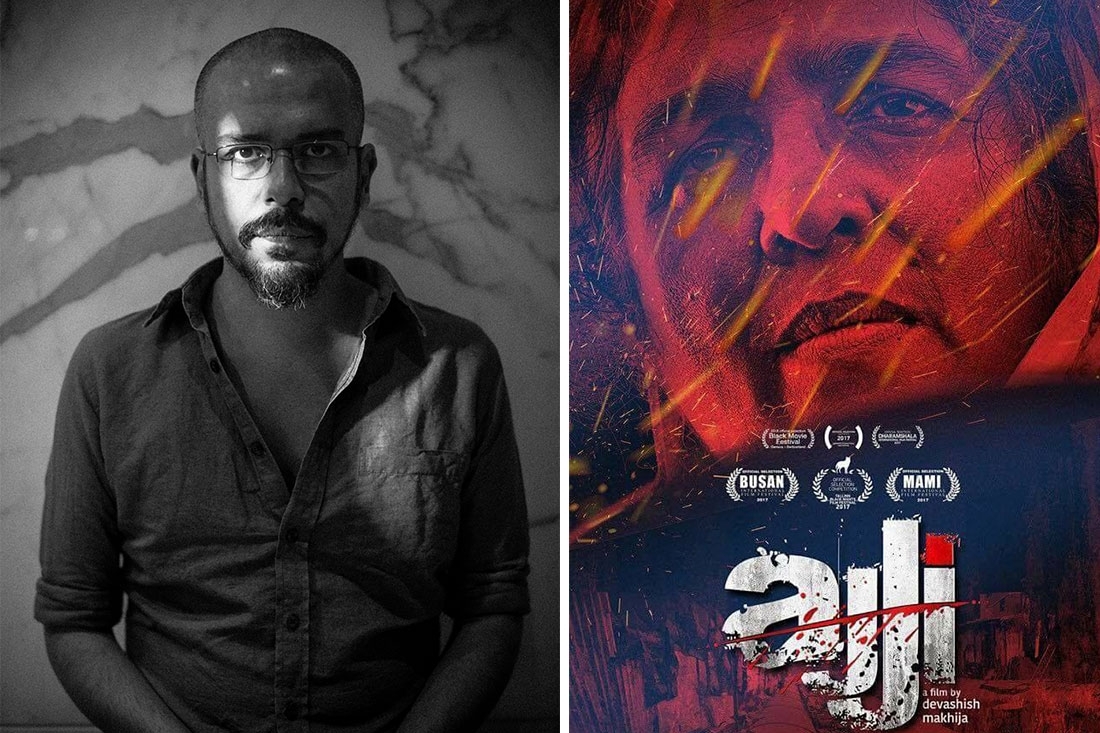

The moment Ajji opens with a scene of a lost grandmother who finds her 9-year-old granddaughter in a garbage dump, raped, something tells you you’re in for a murkier story than you might have been ready for. A dark take on Little Red Riding Hood, Devashish Makhija pulls you into an undeniably gripping narrative that traces the grandmother’s journey in her quest for revenge. Ajji becomes a 104-minute exploration of the idea of justice, or rather, the lack of it.

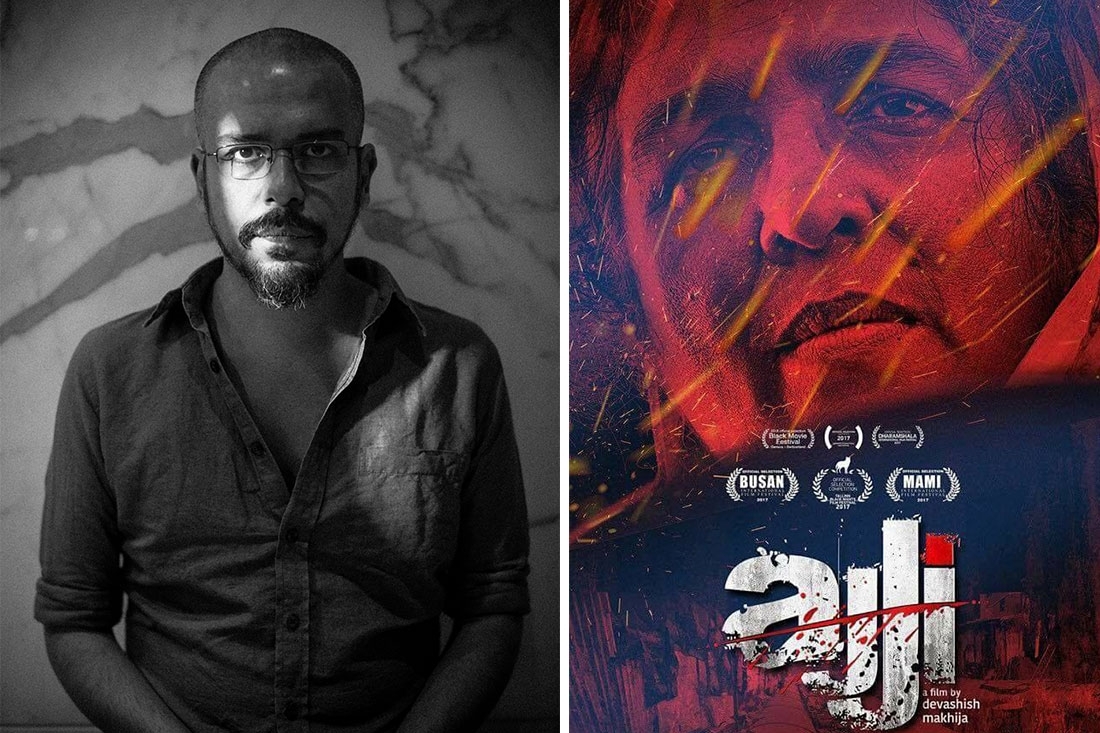

We speak to the filmmaker of Ajji – Devashish Makhija who, after having made a considerable amount of impactful short films, is coming back to explore features. He talks about his creative process, the challenges he faced during the making of Ajji, and everything else that's keeping him occupied at the moment.

When you look back on your journey in filmmaking, how do you think you have evolved over the years – both as a writer-director and an individual?

It has taught me a shitload of patience. I now know how to wait. Interminably. For the right time. For the right opportunity. For the right person. For the right time of day. For that right word. I’m never in a hurry. I’m always on edge though, desperate to get it right. But never in a hurry. I was not like that before this journey kicked me in the butt so many thousands of times.

A still from Ajji

What about filmmaking intrigues you the most?

The fact that it’s a constant process of discovery. I tell my team often that a filmmaker doesn’t fight for the right to make his/her film, he/she fights for the right to discover their film. You might have some clear idea of where you’re heading with the story and the character and the setting and the tone and mood, but you can never know for sure. At most you can just proceed with eyes, ears, heart and mind wide open, and slowly, piece by piece, person by person, you discover your film.

Ajji, at its heart, is about the idea of justice, or rather, the lack of it. What inspired the story? How did you arrive at it and how did it develop?

It primarily stems from many many years of sleepless nights wondering about the unfairness of this world where some people have such easy access to their rights and the machinery of justice, whereas others go through their lives being crushed by constant brutal reminders of how inconsequential they are, and how they will never ever receive even the bare minimum that is rightfully theirs. The anger I have felt on behalf of the wronged Adivasi, the unfairly treated minority, the subjugated lower class, the reviled worker class, I put all that anger into Ajji. Her fight for gender justice is more universal in appeal than all the others I’ve mentioned earlier. And so it allowed me to express my ravenous rage unhindered.

Photography by Ishika Mohan Motwane

You’ve mentioned before that in any form of storytelling, the characters are of paramount importance to you. How did you flesh out the characters in Ajji, especially that of the protagonist?

We did it piece by piece, step by step. It’s impossible to know everything about the characters beforehand. We form our intent as writers, then we write that character sketch, and then we start navigating the story. And as the story grows and morphs and expands, the character starts to change. Character affects story. And story affects character. Ajji was initially a warm, gentle granny not inclined to violence. She was meant to transform radically over the story. And then I met Sushama Deshpande. In her eyes was a fire already. One lit decades ago. I jumped at the chance to use it. I changed the character into one already in turmoil. The new Ajji we fleshed out afresh had spent decades questioning her status in a patriarchal society and family. She had been restless, and never known what to do about it. And bang, now, in the twilight of her life, she got the opportunity. She got pushed too far into a corner. And the fire exploded into an inferno. And the story changed, again.

The last few years saw you working extensively on short films. What did it take to switch back to the feature format? How was the experience?

Shorts gave me unbelievable freedom, the kind I didn’t even know existed in the paradigm of cinema. Then when I came back to features I came back with an inextinguishable lust for freedom. Now I enter meetings with unbelievable clarity. If I sense I won’t get the freedom to discover my film the way I want to, I make a quick exit. The money and the scale doesn’t matter to me. This clarity and this joy I now feel in the filmmaking process, I discovered in making shorts. I plan to switch back and forth between the two mediums for life.

A still from Ajji

Take me through your creative process. What shapes it?

Its very erratic. I have no broad methods. But my starting points are often anger, unrest, agitation. This manifests either in a character, a setting or a story idea. And I take it from there. Throughout the journey I keep reminding myself of that initial emotion I felt that made me embark on the narrative journey. If it’s anger, then I remind myself of that anger I felt at every step, so I don’t lose sight of it. It helps keep the end product streamlined.

What about this film challenged you as a director?

I am not a woman. But to tell this story convincingly, I had to become a 9 year old girl, a 30 year old woman, a 60 year old one as well as a prostitute. I had to think like them. I had to feel like them. Not just emotions. But also physical pain. I had to feel what periods might feel like. I had to feel what forceful violation might feel like. What rheumatoid arthritis might feel like. What an unwanted pregnancy might feel like. The making of this film made me feel physical pain in ways I’d never felt before. But I needed to go through that to be able to transfer the experiences of these unbelievable women to the viewer. These pains helped guide me in every creative decision – from the choice of frame to the choice of music.

A still from Ajji

What did you take away from this experience? What do you hope the viewers take away from the film?

I’m still discovering what I took away from this film. But I do hope the viewer walks away from it a little more empathetic than when they were before they watched the film. I’ve tried to implicate the viewer here, make them feel as if Manda has been raped by Dhavle because we all collectively allowed it to happen.

As hinted on by the teaser poster, Ajji is a dark take on Little Red Riding Hood. Could you tell me a little more about the influences?

In all the adaptations of Little Red Riding Hood across countries and cultures there’s always a Huntsman or a Woodsman who comes to kill the wolf. In some adaptations the little girl herself turns vigilante. But in none of them has the old grandmother been explored. We wanted to see how the most helpless, least likely candidate in a family at the bottom of the social pyramid would go about navigating a task as difficult as this.

As a filmmaker, what kind of themes do you find yourself gravitating towards?

Up until now – Socio-politics and Death. I’m driven sleepless by injustice and inequality. And I’m endlessly curious about death. These two preoccupations have shaped most of my thematic choices. There’s one more theme I’d love to make films about – Sex. But I’ll get to it when I can explore it in ways that will not titillate the viewer but raise questions. More on this when I get to it I guess.

What’s next for you? Are there any projects in the pipeline?

Bhonsle, with Manoj Bajpai. We shoot in two weeks. My book of poetry Disengaged releases in a month or two. A short film Happy is ready, I’m waiting for some money to finish the sound. I am halfway through writing my young adult fiction novel for Tulika Publishers. It’ll be out next year. And another short film I hopefully shoot right after I’m done making Bhonsle.

Text Ritupriya basu & Hansika Lohani Mehtani