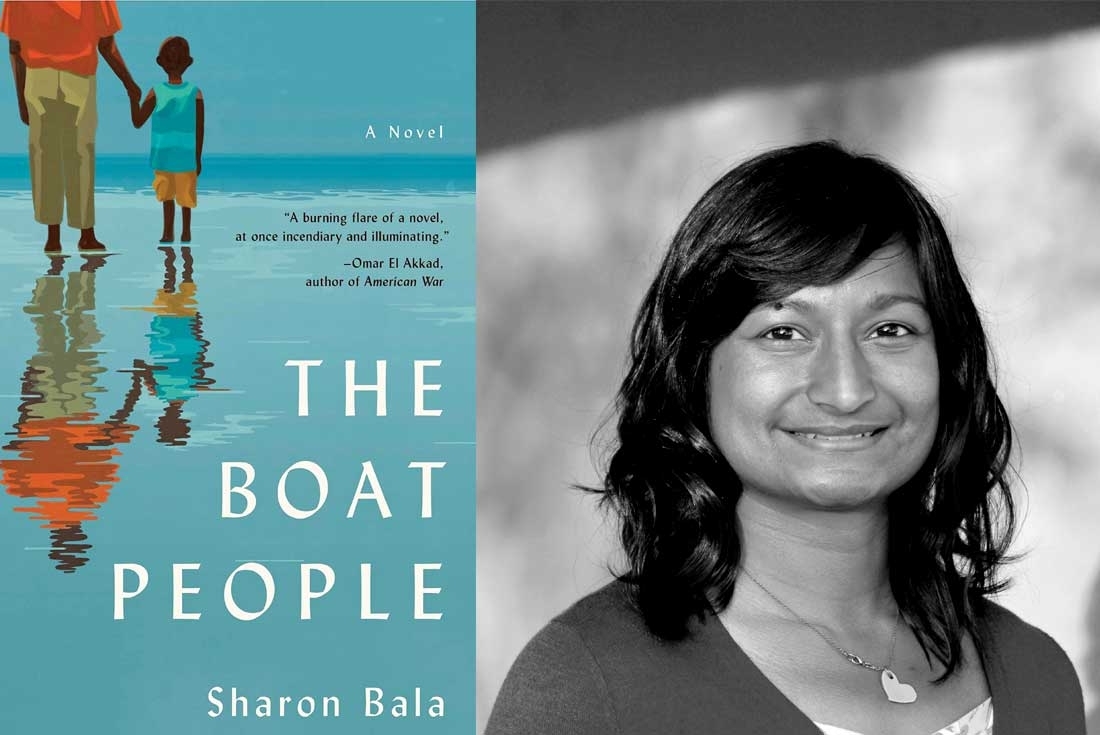

Soon after the Sri Lankan civil war ended, two boats of Tamil refugees landed on Canadian shores. Those ships and their passengers were the inspiration for Sharon Bala’s debut novel, The Boat People.

‘Canada has a reputation, not always deserved, for being an open and compassionate country. In the 1970s we welcomed people fleeing the war in Vietnam. In 1999 we airlifted refugees out of Kosovo. In the 50s we accepted Hungarians who had been displaced by the revolution. But over the years, we’ve also slammed the door in people’s faces. Two examples are the MS St. Louis, a ship carrying Jewish refugees who we sent back to Nazi Germany, and the Komagata Maru, a ship of mostly Sikhs, all citizens of the British Raj, who tried to immigrate to Canada. At that time [1914] Canada was also a British colony and still we turned away our own citizens.

When the two ships of Tamils arrived in 2009 and 2010 we treated the asylum seekers inhumanely, separating families and throwing everyone, even children, in prison. In the years that the people from these boats languished in jail, our country celebrated the 10th anniversary of the Kosovo airlift and the 40th anniversary of the arrival of the Vietnamese. Essentially we were patting ourselves on the back for our past kindness toward refugees while simultaneously acting with incredible cruelty to our newest arrivals. I wanted to explore this dichotomy, of who we actually are versus the image we portray to the world.’

Born in Dubai to Sri Lankan parents, Sharon Bala had a happy childhood. The family moved to the UAE by the mid ‘70s, as it was pretty clear that Sri Lanka was not a safe place to be a Tamil. They immigrated to Canada when Sharon was seven. ‘I grew up in the suburbs of Toronto, in a town called Pickering, which even in the 80s and 90s was quite multicultural. My friends came from everywhere—India, the Philippines, China. Even my white friends were first generation Canadian from places like Poland, Croatia, and the UK. All our parents had accents that were different from ours! Being surrounded by people from all over the globe, early in life, has influenced the characters I create and the way I populate my stories.’

When did your romance with writing begin?

I love the way you’ve phrased this question—romance with writing! It began early. My favourite school assignments were ones where we had to write stories and when I was 14 my mom signed me up to take a writing class by correspondence. I did that for many years. But I didn’t think writing creatively was a viable career so I gave it up in University and began a career in public relations instead. A few years ago I moved to St. John’s, a city where many people write for a living. Suddenly, it seemed less audacious, also I was a little older [in my early 30s] and braver, so I gave it a try.

You have written for various publications and platforms—what inspires you as a writer?

Inspiration comes from everywhere. Sometimes friends bring me anecdotes; they can be incredible or mundane. A few years ago I heard about a woman who spontaneously lost five years of memory. That became a story. I’m shameless about eavesdropping. The other day I was on a commuter train, listening to two girls sitting behind me, and typing everything they said into my phone. Realistic dialogue is difficult to invent and easy to borrow. Other writers, the ones I work with closely and the ones whose work I read continually motivate me. They inspire me to write better sentences, to improve my characters and plots.

How much of your own reality is woven into your writing?

Oh yes, I cannibalise my life for fiction, but probably not in the ways readers would expect. There is a scene early in the book where the newly arrived Tamils are watching an American game show called The Price is Right. It’s a show where people compete for cars and furniture and expensive all-inclusive vacations. One of my earliest memories of Canada is watching this show. My family was living in a tiny apartment and the only furniture we had was a mattress on the floor, a TV, and a couple of plastic lawn chairs. I remember watching The Price is Right and being mesmerised by all the shiny, new things on the television. I had forgotten all about that memory until I began writing my novel.

Can you tell us a little about the story and how you structured it?

The novel is split into three perspectives. At the heart of the story is Mahindan, a widower who arrives in Canada with his six-year-old son. The book tracks their journey, from a fairly normal life in Sri Lanka through their first year in Canada. But I am obsessed with seeing the same story from different angles. So the book also follows Mahindan’s lawyer Priya and Grace, the adjudicator who must decided whether to deport Mahindan or let him stay. As humans, I don’t think we are very good at putting ourselves in other people’s shoes. In exploring the story from three very different points of view, this is what I’m forcing the reader to do.

‘The Boat People—the story of a refugee’s desperate bid for freedom’. The synopsis gives you a glimpse into diverse characters you have created—what kind of research did you do for the novel?

I spent six months researching before I wrote a single word. And then even while I was writing, almost until the very final draft, I often returned to my sources. I researched the Sri Lankan civil war, Canada’s immigration history, the internment of Japanese-Canadians during WWII, the flora and fauna of northern Sri Lanka, neighbourhoods in Vancouver [one of the main settings of the novel]…the research was endless. I taught myself about our immigration system and refugee law. But beyond the text book, I wanted to understand how adjudicators like Grace make their decisions and the impact their jobs—hearing about other people’s traumas day in and day out—have on their psyches. There were a couple of academic papers that were quite helpful in this regard. I don’t know about other writers but for me, I need to know absolutely everything before I start writing. So if a character has Alzhiemer’s Disease—as Grace’s mother does in the book —then I need to know everything about the illness.

Even though you have been writing short fiction for a while, The Boat People announces you as a novelist—how does your approach differ from short stories to novels?

Short stories are sprints. There’s more room for experimentation and ambiguity. And there’s less pressure; it’s easier to abandon a short story if something isn’t working out, or if I get bored. I’m glad I started with short stories because I was able to explore, find my voice, play around with characters and plot and form, basically learn how to write. A novel is a marathon. You take the reader on a journey from a clear start to finish. My novels begin with months of research so from the moment I write the first word, I’m heavily invested in getting to the end.

As a writer, do you feel you shoulder some kind of responsibility towards your reader?

That’s an astute question! One of the best pieces of writing advice I ever got was from the Canadian writer Sarah Selecky who tells her students to write the stories they would like to read. I do feel some responsibility to the imaginary reader— who is myself—but only in very specific ways. I’m aware, especially when I’m revising, of the things that annoy me as a reader and I try not to commit those sins. As a reader, I appreciate when the writer respects my intelligence, and leaves mysteries for me to solve, some space for me to insert my own imagination into the story. So as a writer I leave a little room for the reader to make their own adventure.

And lastly, what can we look forward to after The Boat People?

I’m working on a new novel and putting together a collection of short stories.

Text Shruti Kapur Malhotra