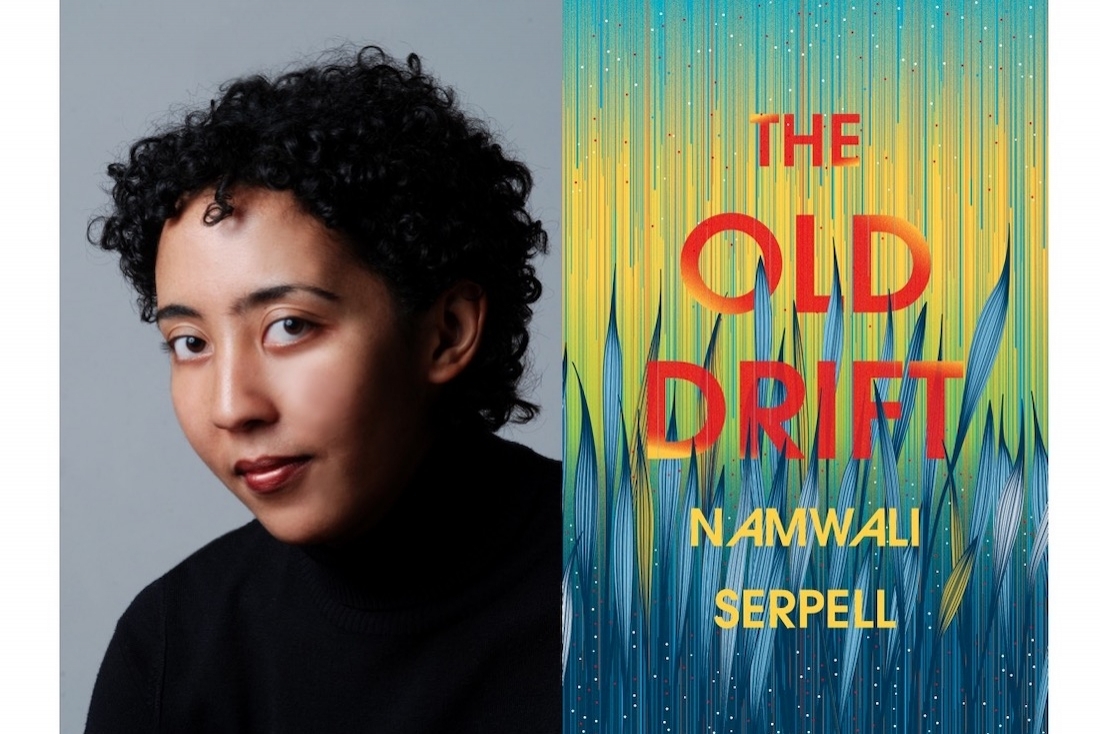

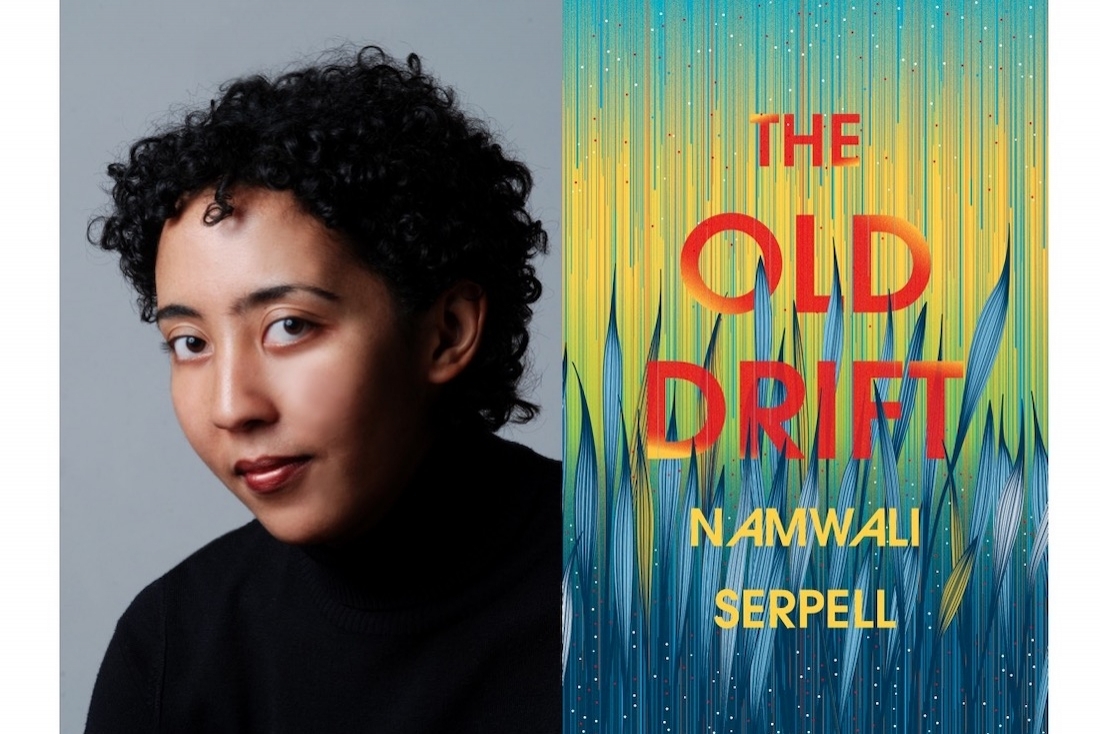

Imagine a cemetery that gives birth. As countless colonial settlers from all over the world—England, Germany, India, Poland, Australia and America rest in peace at The Old Drift in the game park at the Victoria Falls, a new life emerges. One that is a work of art listed among the top 10 literary debuts of the world this year. The Old Drift has a story too powerful for introductions. How its creator, Namwali Serpell, was introduced to writing perhaps best explains its beginnings.

'I became a writer when I became an immigrant. In 1989, my family moved from Lusaka, Zambia to Baltimore, Maryland in the U.S. I still have a small red spiral notebook from around that time. Inside you can find, in painstaking cursive, my full name, my address, and a set of ideas for stories: “Friends Forever… I hope,” “Gymnastics and Horses Don’t Rhyme,” “Brainy Magic.” They vary in genre from murder mystery to sci-fi, family saga to melodrama, but it’s all patent autofiction. What strikes me now is that each one reflects a young person trying to make sense of a new world. I was surrounded by people who acted in unpredictable ways, who spoke in unfathomable accents. I had a hard time making friends. Words, stories, books—this was consistent, this was a home to me. It still is.'

Tell me a little about your first memory of the written word.

My father taught me how to read. I must have been four. He took a navy-blue folder—I remember the gold line drawing of the aeroplane on the cover—and taped horizontal strips of card inside it. Then he cut paper squares and drew the letters of the alphabet on them. I was left to play with them, shuttling them around in their slots, like solo paper scrabble.

“I was surrounded by people who acted in unpredictable ways, who spoke in unfathomable accents. I had a hard time making friends. Words, stories, books—this was consistent, this was a home to me. It still is.”

What inspired The Old Drift?

I’ve been writing this novel off and on for nearly twenty years, and it incorporates many cultures, periods, genres, and ideas. So it’s hard to pinpoint what one thing inspired it. I can say that I got the idea for the title in 2013 when I first encountered The Old Drift cemetery in the game park at the Victoria Falls. I was fascinated by the fact that these colonial settlers from all over the world—England, Germany, India, Poland, Australia, America—had pitched up and died at this spot within such a short span. My friend and editor, Michelle Quint, who was visiting Zambia with me at the time, suggested I name the novel for that place.

Can you give me a blurb on the book in your own words?

The Great Zambian Novel you didn’t know you were waiting for.

What is at its core?

A small error whirls into a cycle of retribution between three Zambian families—white, black, brown—that travels across the world and the twentieth century into the near future.

How did you find and build your characters?

My characters came to me over a long period of time, beginning in the year 2000, when I was at university. The most interesting discovery story concerns the very first character I wrote, a woman whose lover knocks her up, then abandons her (or so she believes). Heartbroken, she lies down to weep… and doesn’t stop for decades. In 2012, a friend sent me a link to a video called “Afronauts.” It was a trailer for a photography exhibit by Cristina de Middel that began with title cards explaining that “In 1964, in the middle of the space race, Zambia started a space program that aimed to put the first African on the moon. The director of this unofficial program was Edward Makuka [sic].” The one female “Afronaut” in Edward Mukuka Nkoloso’s space program was named Matha Mwamba and she got kicked out when she got pregnant. When I was mapping a chronology of the novel, I realized that Matha was pregnant at the exact same time as my character. They were the same person! Suddenly I understood my character’s backstory—her childhood and teenage years, why she was really crying—and why her grandson would go on to become obsessed with aeronautics technology. My mother had asked me to rename my character anyway—it’s such a common name in our family that she worried our relatives would project themselves onto her. So she became Matha Mwamba.

“The Old Drift is, like my little red notebook, an immigrant artifact: a meditation on migration and moviousness, the drift of people and culture and borders and time itself.”

How have your roots influenced this story?

The Old Drift is, like my little red notebook, an immigrant artifact: a meditation on migration and moviousness, the drift of people and culture and borders and time itself. I grew up in a mixed household—a white former Brit for a father, a black Zambian for a mother—in a very multicultural Lusaka. We were close friends with other mixed-race families and I went to a school run by Zambians of Indian heritage. There is a lot of interracial love in the novel, though no exact matches to my family or to my experiences as a U.S. immigrant. But I wanted to capture this sense of cosmopolitan life in a majority black African country.

How does politics affect your writing?

The novel traces the history of Zambia from the arbitrary marking of its borders in the nineteenth century through colonial protectorate status and the freedom fighting days for independence to its current state as a democratic nation with socialist tendencies. Marxism—proper, diluted, tainted—snakes its way through this tangle of history. The last third of the novel, set in the twenty-first century present and future, depicts a love triangle between three young people who are trying to start a political revolution. (“Very current affairs,” a bystander smirks.) I coordinate various contemporary political issues in that part of the novel: the neocolonial influx of capital into Zambia, particularly in the NGO, technological, and medical sectors; the capitalist ideology to which we often freely submit through cultural and social norms; and social media as a way both to spur and to manipulate political action.

What was the toughest part of making this debut?

Fact-checking. The novel swims in speculative fiction—fairy tale, magical realism, science fiction—but I am very keen to get historical and cultural details right. Because the novel is so sprawling, it was hard to verify my facts on: tonsure practices at Tirupati, bungee jumping at the Victoria Falls, the export of He-Man figurines to Lusaka, the exact look and feel of Great Zimbabwe, Shiwa N’Gandu, and Tirupati, the specific receptors that need to be blocked in an HIV vaccine, the correct slang for Zambian teenagers in the eighties, and so on. I’m thankful for all of my informants—family, friends, acquaintances, strangers, and the blessed internet.

“I wrote this novel off and on through my twenties and thirties, so it and I have been, let’s say, mutually transformative. It made me a writer—my first published story is an excerpt from The Old Drift. I learned a great deal about where I’m from and how my strangeness makes perfect sense in that context”

Can you take me behind your creative process?

No. But I can’t take me behind my creative process, either! If I knew how it worked, I’d be too bored to go on. The only pattern to it is this: there will be a very dull, low, empty spell in my life. Then I drink coffee or have a random chat or ride on a train and suddenly all these ideas spring forth out of that vacuum—characters, words, plots, images. I scrawl them down or tap them into my phone. Later I sit, open the laptop, and write. Revision may vary.

One part of The Old Drift that transformed you...

I wrote this novel off and on through my twenties and thirties, so it and I have been, let’s say, mutually transformative. It made me a writer—my first published story is an excerpt from The Old Drift. I learned a great deal about where I’m from and how my strangeness makes perfect sense in that context—Nkoloso, the man who tried to get to the moon, is the presiding spirit of the novel for a reason. Somewhere towards the end of the editing process, I was rereading the novel and at a particular moment, I got chills. It never happened again—I still fret that I somehow edited or changed it in such a way as to destroy the rhythm or the tone that had sparked that feeling in me. But I loved that moment. It felt like I had given myself a gift. Thank you for this question. It makes me grateful for this novel in a new way.

Who are your favourite authors, both old and young?

Questions like this don’t make sense to me. When I won a prize for African fiction in 2015, I split the reward with the other four shortlisted writers because, as I said then, “writing is not a competitive sport.” I’m a literature professor and a writer, which is to say, I’m a reader at heart. I love too many different authors for too many different reasons (moved me to tears vs. to laughter, for instance) to decide which ones to select over the others in answer.

What is next?

Oh, so much! I have two nonfiction books on the way: one through Columbia UP on why I love-hate American Psycho; the other through Transit Books about unusual faces (biracial, animal, thinglike, digital). And I am working on two novels: one about vengeance, set to the key of Nina Simone’s “Pirate Jenny”; the other, a modernist crime story about mourning.

Text Soumya Mukerji