The Artist

My father [Raghu Rai] photographed me every day. The camera was always there. My first camera was a red and white film camera. It was a good-looking instrument.

I think it was given to me because otherwise I would go for the camera which was always there in my father’s hand, and no photographer wants his camera taken away, even if it’s by the daughter. So that happened—a photographer’s daughter had a toy—and that was a camera! That was the beginning of my journey in photography.

When I look through the viewfinder, my attention is focused and I am in the moment. When I visited Kashmir, my love for photography and the need to capture the moment as it spoke to me became even more important.

The Inspiration

I met a 5-year-old boy at the Khanqah mosque in downtown Srinagar, Kashmir, a place I often go to. He spends much of the day playing in the alleys, dressed in typical Kashmiri attire and full of life. I recall one of my first conversations with him.

He looked at me and asked, ‘Auntie, are you on the side of India?’

I thought a while and answered, ‘No’.

Even though he was a little child, I felt strangely intimidated and was cautious with my answer.

‘Then, from the side of pakistan?’ he asked.

‘No,’ I answered.

The natural drift of our conversation and my own curiosity led me to ask him, ‘And what side are you from/on?’

He said, ‘I am from/on Allah’s side!’

He seemed to know his answer. The ‘idea of Allah’ is being redefined in every part of the world, across societies and age groups. This is especially true of the tumultuous parts of Muslim world.

My current body of work looks at denial of home as a form of violence, exclusion and cultural erasure. Through my photographs I have been collecting fragments of people’s homes, which they carry along as an image or an object or a story, and using these elements to create physicality—to revisit that which is lost, and the uncertainty of return. These remnants create an album of memories. The idea of re-visitation here is very important.

People sometimes only have an object—a set of tea cups—or images of their houses [now broken, abandoned and in ruins] sent to them by those who stayed back, or they look for their lanes on Google maps. It is heart-breaking to imagine what we are without our homes.

My debut show, Ground Zero, looks at Architecture as evidence and the site as witness. It looks at emotions embedded in spaces that are dehumanised, traumatised and accepted.

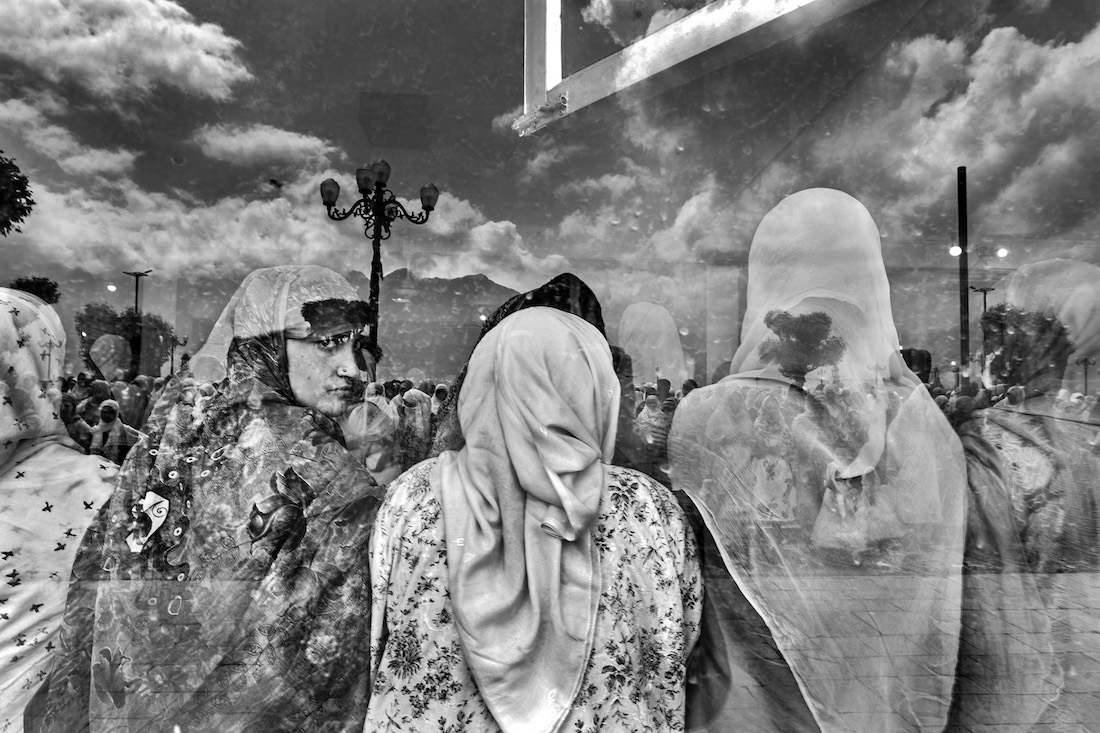

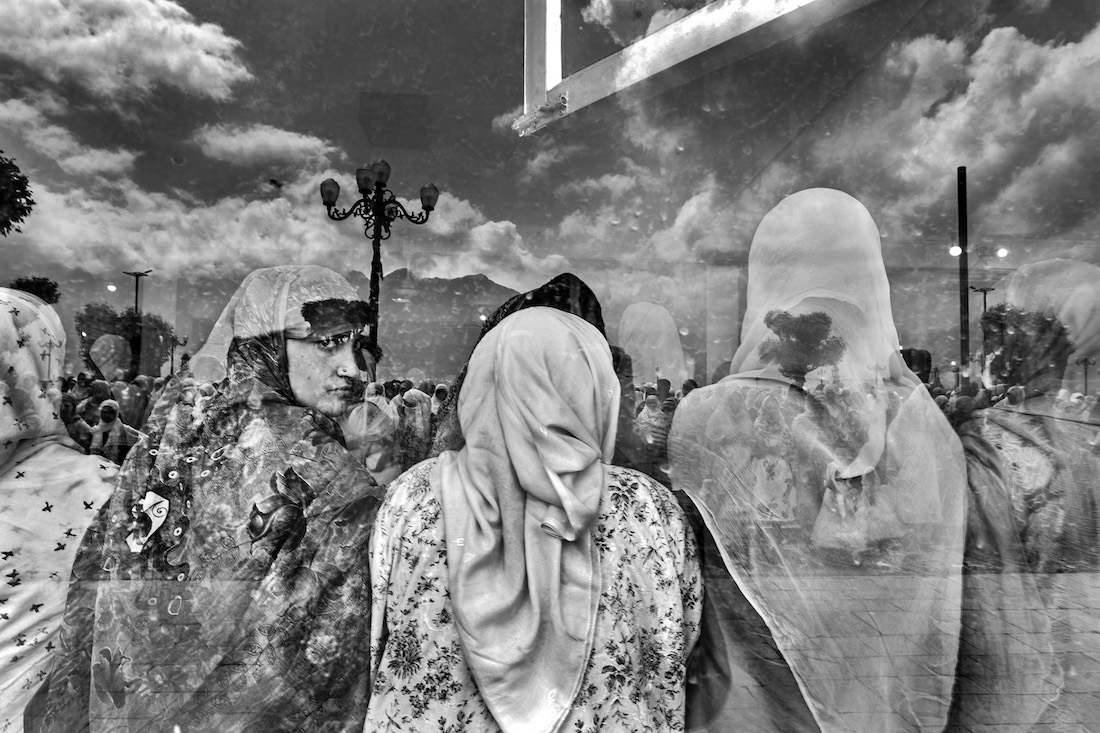

The Women Of Kashmir

My visits to Kashmir have become more frequent over the last few years. Kashmiri society stands demonised in national debates. A defining aspect of a conflict zone is that the world ceases to acknowledge the ‘individual’ and instead stereotypes the entire ‘community’.

It seems conflict is a profitable business in today’s world. It is sold as a commodity and often at a huge cost to humanity. In India we see this malediction sprayed across all channels. In the cacophony of voices that are heard, to speak without reflection is the norm.

While men are the direct targets of violence; the trauma for women and children is of no less a magnitude.

They are vulnerable. Through this project I tried to explore the ordinariness of daily life of both women and children seemingly forgotten. What are their means of survival in the conflict that has surrounded them for decades now? This has become a very poignant question for me.

Losing a child is possibly the greatest emotional pain known to humankind. Despite the profound grief, there is resilience and a will to survive. Nurturing this feeling is the only hope and women have a significant role to play. Effort is required from the world, from those who care to reach out. I believe that there are no victories in war.

Text Soumya Mukerji