Machine Matter

Machine Matter

Munem Wasif's tryst with the geographies of his homeland and its connecting borders can be traced back to 2014, the year his solo show, his first ever in India, began to shape-up. Never diverting from his documentary-like approach to politically and socially influenced issues the land is perplexed with. It all began with his interest in the idea of borders and maps and their origins, which were eventually shaped into a series of recurring frames titled Land of Undefined Territory.

'I started working on Land of Undefined Territory in 2014 while I was at a Public Art Project, No Man's Land, at the border of Bangladesh and India, organised by Britto Arts Trust & Shelter Promotion Council. I started with photographing a small hill and tried to create a series of mundane landscapes where nothing seems to be happening, but one can see traces of industrial and human intervention,' remarks Munem. His decision to extend this concept of an apparently insignificant land between borders brought the same to Mumbai's Project 88 art gallery.

Land of Undefined Territory

Exercising his knack for archival documentation, the photographer attempts to expose the tense political subtext that encompasses a territory presumably no different from any other. 'For a lot of people in that region, this border doesn’t make sense, as their lives were rooted in that land for hundreds of years. They share the same language and have relatives in both parts of the land. Just a few decades back, for us, it was a part of the larger Bengal. Now, the same land has higher fences and the border has become the most violent one in recent history.'

His curiosity to decipher the dynamics of land and its ownership led him to Sharpin tilla, the now immortalised hill situated between Sylhet and Cherrapunji – left empty, barren with traces of meddling at best. 'This particular hill was exciting because of its sense of repetition. You go from one place to another place and they all looked similar. This repetition created confusion, the present felt like the past. It is a hard experience to interpret. Each field felt like I've seen it before, almost like Déjà Vu!' remarks Munem as he set out represent the landscape through a repetitive series of photographs, rendering a strange illusion.

An important aspect of finding representations to define said landscape, were the workers who made a living off of it. With no crop in production in the zones, they managed to earn a basic living and confided in a passing photographer, stories of seeds, songs and their lives. Munem's portrayal of these workers sees them as part of the site as opposed to entities that stand apart. 'I photographed them in a way where you don't see them properly, they are blended in the landscape. When you go to the top of the hill you see these workers doing the same thing again and again in repetition. The hot wind of summer, rustic landscape, and bright light enhanced the presence of industrial intervention, the feeling of unknown, and boredom to some extent. The series of landscape was extended in a three-channel video over the years which is not shown in the ongoing show at Project 88.'

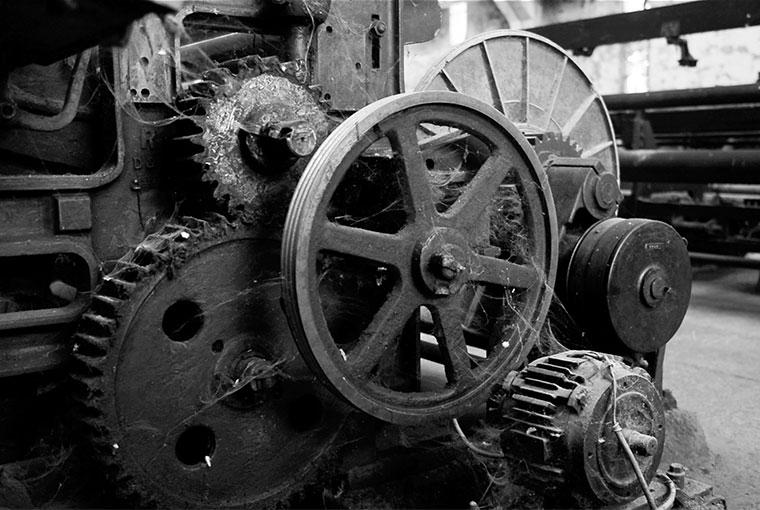

Machine Matter

Machine Matter, on the other hand demonstrates a shift from workers to the machines and their sorrowful tales that reveal memories of an increasingly distant industrial past. One drenched in colonialism, starvation and deprivation. What now lies in its wake is a symbol of a fight long lost, and serves as a constant reminder of a fight long lost. Munem delves into his experience shooting for this exhibit.

'In Machine Matter, the frames are still but it's a moving image. The movements are subtle. The combination of body and the details of machines create a particular mode. The absence here creates a presence. Sound was the most critical part of Machine Matter. I was interested to produce an electronic sound creating a psychological space, which, to some extent is supposed to bother the audience. Collaboration with Saadul Islam (musician) was an extremely crucial aspect of realising this.'

Moving on to Wasif's third installation at Project 88, the cyanotype prints of Seeds Shall Set Us Free command a history that outlasts its existence by hundreds of years. The foremost enforcer being the rich seed banks of Bangladesh's Tangail, harbouring the farmers' movement, Nayakrishi andolon that changed the face of agricultural practices for the better. Munem speaks of his first visit to Tangail and the consequent research employed in the making of Seeds Shall Set Us Free.

'I was amazed at the variety and similarity of the local seeds. Each seed has a local name instead of a generic number. I spoke with farmers, researchers, historians. Soon, I realized that rice is not just a food crop for us. It relates to our history, development and culture. The movement of farmers was not about organic agriculture, rather it was about preserving biodiversity and fighting to reclaim sovereign control over their land and livelihood.'

Having uncovered the many historic and cultural implications tied to rice, from being an intrinsic part of wedding ceremonies to an offering for the deity of harvesting, from depicting the journey of seeds altogether through colonial oppression to now being celebrated in the country's largest harvest festival Nabanna, rice slowly makes its way back to reclaiming the title of 'Gold of Bengal.'

As far as the significance of its medium goes, it comes with its own trail of meanings and cultural ties. 'I thought cyanotype would make for an interesting (pseudo) method to reproduce and archive these seeds as it was used as a blueprint to reproduce notes, diagrams, and architectural drawings. I was also interested in the analogue printing process to make cyanotypes, as each print will be unique with its shades, dust and text, accepting the odds and the accidents. The whole process also reflects the idea of biodiversity in nature, where it embraces and connects all the biotic and non-biotic things in our ecosystem.'

It goes without saying that a project dealing with the intricacies of territories, borders, ecology and their nexus, would have a few obstacles to overcome before it could be the show it turned out to be. Its creator takes us through the admittedly varied challenges usually associated with a diverse show as is Jomin o Joban. 'Each work has a different kind, form, and language. From land to seeds to jute, in each work, the process of editing is very crucial. There is a particular form of sequence which has a specific meaning that shifts and creates a particular kind of speed.'

Munem's latest offering stands to deal with the grim realities of modern day Bengal and proceeds in doing so in an almost soothing manner. The solo show promises to take its viewers through a world of stories about everything from agriculture to machinery, lying at the crux of two nations, one that the photographer hopes connects with every individual at a personal level, may it be emotional, political or both. 'In all the works, there are historical connections and resonance from the subcontinent. And a lot of times there were similar struggles. I hope the audience gets clues and draw their own interpretations, as I wasn't fully invested in the literary narrative while developing the show.'

Jomin o Joban - A Tale of The Land will be on display till the 6th of December, 2017 at Project 88 in Colaba, Mumbai.

Text Shristi Singh