Revisiting our conversation with the acclaimed artist, architect and sculptor, Satish Gujral.

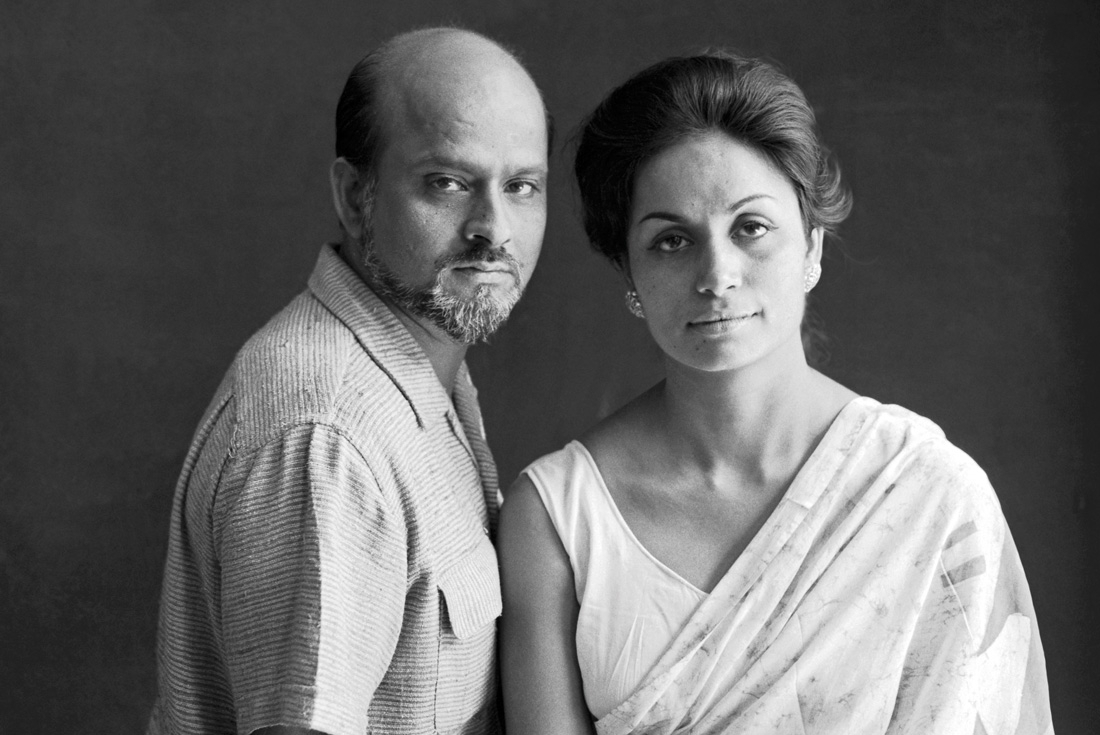

I am one hour early for our meeting after having over-anticipated traffic, but I don’t know how that hour passes. At Satish Gujral’s house in Lajpat Nagar, I am first seated in the waiting area, and then met most warmly by his wife, Kiran, who is on a wheelchair. She is most concerned that I should not be sitting on my own and takes me upstairs, offering that I meet the artist way before the scheduled time. I say I am fine with paying for my untimely arrival, and taking in his many artworks that adorn the two floors in front of me. There is a gold-glazed sculpture of a man in a short coat with a black bird in hand to my left, and a bull to the right. Both appear to embody the artist himself—a bit of a magician and a fighter who went against every circumstance to become a master of many arts in times when switching discipline was seen as ‘stupidity’. Perhaps the last of the living Modern Indian Artists, the man who has been in the company of greats such as Frida Kahlo and Faiz Ahmed Faiz, now sits before me, humble in his years of award-winning work and success. He turned 90 last December, medical equipment to one side, and his artist wife Kiran Gujral to another—the two sides of his survival support. In front, his son Mohit, a noted architect and my facilitator for this interview, starts the conversation in half-Punjabi, half sign-language, to tell him what this is about. This is a story about the stuff that icons are made of.

How silence struck

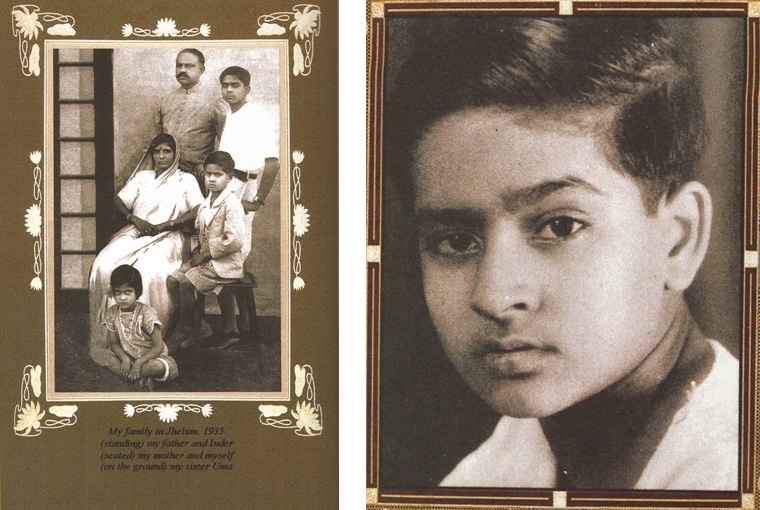

‘My beginning as an artist was not accidental. It happened when I was very young, only eight years old, and lost my hearing,’ recalls Satish. Born in a small river settlement along the Jhelum to a lawyer who was to later turn into a Gandhian, he lost his hearing as a result of the medical complications that followed a bad fall in the river. Neither ‘English medicine’ nor the help of hakims could save him from the permanent impairment.

‘He got into art only because of his handicap. Not knowing what best to do with him, his father took him to art school,’ says Mohit. Before going to the prestigious Mayo School of Arts in Lahore however, Satish was sent to a school for the deaf and dumb in Old Delhi, which he has described more as an ‘asylum’ in his autobiography. He was a misfit there and his other faculties were far more developed, observed his warden in a letter to his father that led the latter to change his mind.

‘He took me to art school and got me books to read. Urdu language literature. I read a lot of poetry and the writers at the time—Munshi Premchand, Ghalib, Iqbal and so on. At the time there was no children’s literature available in Urdu language or none we knew of, and unfortunately I had only learned Urdu before I lost hearing. My father brought me books about historical heroes such as Lala Lajpat Rai and Bhagat Singh. Incidentally, I got involved in politics and these heroes were almost part of the family. Seeing my family members become a part of the Nationalist movement inspired me...I wanted to get fully involved myself.’ Destiny thought differently. ‘My father decided that I go to art school because the graphic language did not require hearing. He found a school which was near my hometown. With great difficulty he convinced the school principal to admit me. In those days, a handicap was a huge thing.’

Left: Satish Gujral with his family | Right: Young Satish at the Mayo School, Lahore, 1940

The foundation

While his father used his influences to land him a seat at the Mayo College of Arts (now National College of Arts, Pakistan), he was far from being treated like a regular student. ‘During the English rule, the government set up one art school in every state. The Lahore school was the last, because the English rule in Punjab was the last. I was told to keep sitting in the same class for five years and that no merit certificate could be given. This way, I came to learn painting, carpentry, sculpture, stone carving, and traditional crafts. In other art schools you could study just one subject—that was painting and sculpture. But the Lahore Art School was different. It was handled by the father of Rudyard Kipling—Lockwood Kipling. After having studied arts in England he wanted to open an art school in India that in its curriculum held the tradition of India. In Indian tradition, you learned every subject. Painting, carpentry, graphics, carving and so on. Kipling used the same approach in the Lahore school. In the beginning, I was disappointed. I wanted to be an artist and I was learning the job of a mistri (toolman), carpenter and a stone-carver. I did not like it. But late in life, it came handy,’ he recalls. It was this multi-disciplinary learning that would later help him go from painting to muralism to architecture effortlessly.

Revolution and the romantics

Satish was still a young boy at Mayo when the wave of Nationalism took over the country, and living with his older brother Inder (former Prime Minister Inder Kumar Gujral) in the same hostel made him seek inspiration in politics and revolution. ‘The Marxist influence came on me through my brother and my father. My family went to prison during the freedom struggle. While my father became a congressman, my brother (Onkar, step-brother) became a criminal! Following him, so did I. As did many poets and writers. Being a Marxist was not easy. You were not given the freedom to move. But it was very romantic. Almost all great poets of that time, such including Faiz Ahmed Faiz, roamed there. By accident, Faiz, who had not become a poet by then and was my brother’s teacher, had been given a small house near his hostel,’ he recalls. ‘Every evening, he came to the hostel and read his poetry. It had not yet been published, but he wrote. One day, my brother told Faiz that I wanted to read his poetry but I could not hear. So if he’d lend his handwritten book for one night for me to read. Faiz not only did as he was told, but also sat with me. So he became not only an influence but a teacher. I remember those three nights I read him without end.’

The artist says that Faiz’s words keep echoing in his mind to this day, and he remembers fondly the last time that he met the legend. ‘I remember when many years ago, he came here and read his poetry to a group of friends whom I invited. This was during his last years. Then, there were many other poets who were not my friends, who affected me. One was Sardar Jafri.’ While Faiz’s unpublished poetry from decades ago comes to his lips even during this interview, he says the way it affected his art must not be misunderstood.

‘Remember one thing: A painting can portray a painting. But it does not mean it’s just portraiture. Graphic has its own vocabulary. The poetry affected me. And I tried to paint the effect, not the idea.’

Partition

Idealism was to be short-lived; reality would soon rip apart Satish’s world. After Mayo, he moved to the JJ School of Art in then Bombay, which too was a vision of Lockwood Kipling and hence kept in mind the same progressive sensibilities in art. Perhaps unknowingly, choosing it over the conventional Santiniketan school in Bengal on which he once had his heart set was another unconscious move in the direction he was to lead. ‘In my time there were all those who later came to centrestage in Modern Indian Art. My course fellows were behind me. Raza, Souza, Husain, Gaitonde...they all became dropouts. I dropped out too, because Partition had arrived, and as a result there were economic difficulties. I came back to Punjab. And everything happened overnight. It affected me. It made an artist out of me. I got to paint almost everything that had been affected by the Partition.’ Around this time, Satish’s paintings were dark and full of angst and there were few buyers for it, but he had to keep going to make ends meet. ‘I sold my paintings. There were two or three but there was no choice. There was not much money in the family as the farms were taken away. So after Partition, I devoted my time to finish my paintings. Partition brought fresh change in our lives. Not only in art but in life.’

Muralism

While he was still painting and shortly working as a graphic designer for a government publicity department in Shimla, he became friends with American architect Ted Bower, who helped the choices he would later make. Before that, however, he would meet archaeologist Charles Fabri who introduced him to Mexican arts, particularly muralism. It was then that he applied for an artist’s scholarship in Mexico and fight foul play to land some precious years of world travel and a resultant transformation in his artistic outlook. After paintings with Mexican influences came murals. It was here that he also came to meet Frida Kahlo, who was smitten by India’s spirituality, and her muralist lover Diego Rivera. His style stayed on with him. In his autobiography, he writes, ‘On our way back from the crematorium (after Frida’s last rites), Diego asked me to come with him to the Teatro de los Insurgentes and see the mural he was painting. It was clearly an invitation to assist him in finishing it. I accepted with alacrity. The assignment roused my interest in mosaic and the use of different materials for making murals.’ Among those who came to see this mural, which he had assisted, was architect Frank Lloyd Wright who would impact his designs significantly.

Architecture

By the 1970s, owing to the general apathy towards the ‘plastic arts’ and the need for change, he had stepped over to architecture, without any degree or training in the discipline. It was not the traditional pen-and-paper-practice as traditionalists knew it. His was a fluid sketch to form style because as a trained carpenter and stone-worker, he had already built the structure in his head. Architecture took from both the other forms he had hitherto practised—painting and muralism. ‘If I know what I could be doing tomorrow, I shall do it today! Mediums have limitations. I found that art has no limitation. You can do creatively almost anything. If you try to go into history, most of the greats who went into architecture came from the arts,’ he reminds. Some of his prominent architectural works include the Belgian Embassy, the Modi House and the Goa University. In all his years of practice, the artwork that took him the longest to make was the Belgian Embassy in New Delhi, selected by the International Forum of Architects as one of the finest buildings of the 20th century. ‘I started it with two assistants and one supervising engineer.’

Untitled painting, 2000

Architecture is a practice in patience, says Mohit. ‘From the time that a building is conceptualised to when it’s made, it’s already five to six years. And for the artist, it is frustrating because his work is already done and he cannot do anything but wait before the desired result comes up. Someone else, the mason or the contractor, has to do the construction and you have already done all that you could!’ He adds that Satish’s buildings were a breathing work of art thanks to an early learning that followed his meeting with Frank Lloyd who had told him back in Mexico that his architecture needed no murals because he never designed dead walls. ‘His forms were so powerful. There was no space for art. Or sculpture. Each building was a sculpture in itself,’ says Mohit.

Changing colours

Mohit takes us through another kind of change that you see in his art over the decades—one of colours. ‘If you look at the transformation of his art, you also see the kind of transformation in the use of colours. There was the childhood angst as a handicapped person, then the whole exposure to the Partition. It was a very dark period in his life. The art he created then didn’t sell easily because nobody wanted a dark tale hanging on their walls. They wanted happy subjects especially if you come out from the Partition. But over the years he found success, family, all those evolutions in life, so his art also grew happier. It became more decorative. So there was a music series of paintings. Around this time he had a cochlear implant in his ear for hearing, which led to more colour in his works. He experimented with hearing for a year or two but he gave it up. When you haven’t heard sound for the longest time, it is very disturbing because it’s almost like being reborn as a child. You learn each word all over again as if you’re learning the world again. It became very disorienting for him.’

More mediums, more possibility

Satish did not make a conscious effort to change his artistic discipline; it occurred in flow. ‘In the olden times, an artist used to be everything. A painter. An architect. A stone carver. And so on. So in my later years, I allowed myself to take up whatever medium came to my mind. Once, an artist told me he wanted to paint but he was not “allowed to”. I said, “what is not allowed!?” So in my life, from time to time, I jumped one medium to another. It happened automatically.’ That is not however, to say it came easy. ‘The challenge comes when you jump from one medium to another and even in the other, you find as much possibility as you had in the previous one. Most of the artists think that if they leave the medium that they have already gained success in, they may not find the same chance in the second. I had already made much success and to leave that wasn’t easy. Most of my friends thought I was stupid. Leaving something that was so successful for something that may not give any returns. But if you are sincere, there’s always scope. It was very satisfying...to me, the greatest satisfaction comes from change.’ Mohit remembers that for his father, ‘it was a constant up and down because in his early years he did murals, went into sculpture, and went into architecture’. But he highlights the interconnectedness of these forms of art as a whole. ‘All these are dimensions of the interactive space; they all borrow from each other.’

Satish observes that at present in art, there is more change than has been in the last 50 years, and he hopes the spirit will go strong. ‘Believe in yourself and in life so when you look back, you can say it was a journey well travelled. I did what I wanted to do; I did what my heart told me. I did not do what people wanted me to do. Or what people wanted of me. You are not a commercial artist that you’re creating to please an audience. You’re there to please yourself,’ he reminds.

Our conversation with Satish Gujral was first published in our Art Issue of 2016.

Text Soumya Mukerji