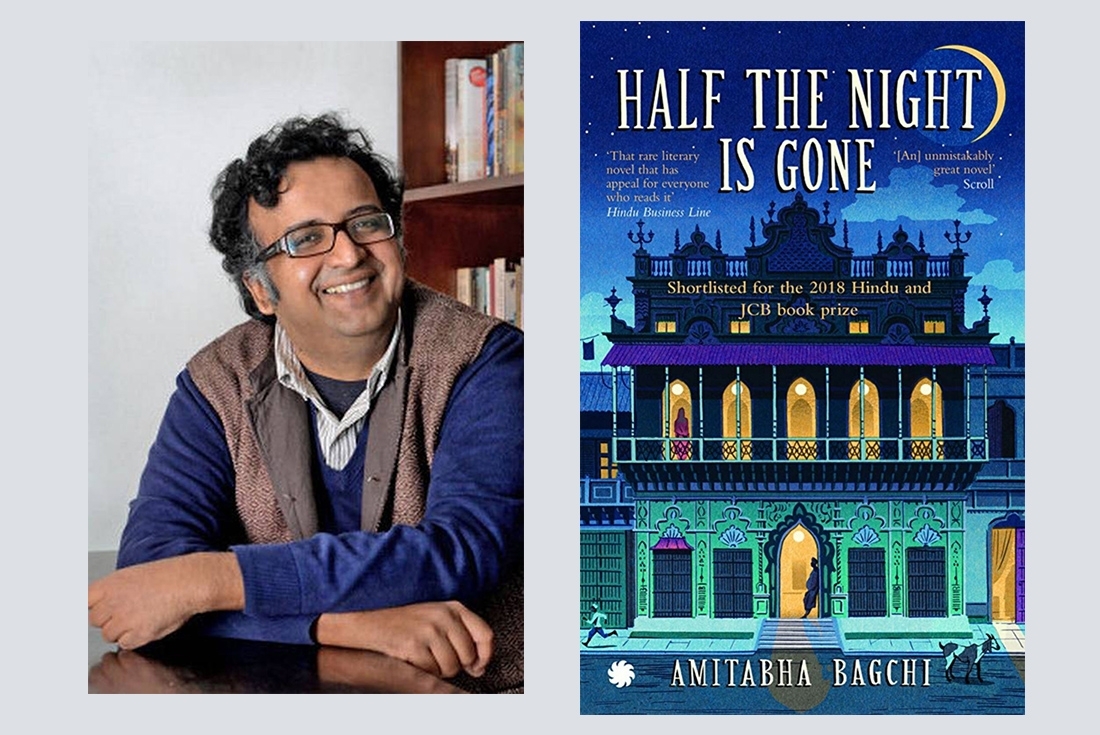

The winner of 2019 DSC Prize for South Asian Literature Shortlist, Amitabha Bagchi’s Half the Night is Gone has been making waves in literary circles ever since it came out. Alternating between a narrative set in pre-independence India and a novelist’s letters, the book’s writing is a testament to the writer’s descriptive prowess. We got in touch. Excerpts.

Were you always interested in reading? Tell us a little about your own journey as a reader.

I did read as a child and into my teens, but, apart from that, I think my early influences were also oral stories. My father told me bedtime stories, which he normally made up, and he also had a knack for making interesting narrations out of day-to-day incidents. If we return to reading, I read the usual things, to begin with, Enid Blyton, moving on to Agatha Christie, which was a natural progression when I was a child. In college, I was first exposed to Indian English fiction because there was a course on it which I registered. I was also exposed to Amitav Ghosh’s The Shadow Lines in a course in college. Reading that made me feel I could also write. It was in graduate school in the US that I first began to read Hindi and Urdu in a big way, and for the next ten or fifteen years I would say that the bulk of my reading was in those two languages, novels in Hindi and poetry in Urdu. As for currently, I just finished reading Qurratulain Hyder’s Safina-e-gham-e-dil, translated into English as Ship of Sorrows by Saleem Kidwai.

Coming to your latest book, how heavily would you say you draw from your personal life experiences while writing your books, Half the Night is Gone in particular. For example, how did your personal relationship with religion affect the way this book was written, keeping in mind how heavily the book draws on the Ramcharitamanas?

I think all writers draw heavily from their personal experience but often that personal experience gets transformed beyond recognition, to the point where it is no longer of any interest whether the text draws from the personal or not. In Half the Night is Gone I myself have lost track of where my own lived experience comes in and where the things I have read and heard over time have made a mark. As for religion, I am not a religious person and in some ways this book is my attempt to bridge the gap that separates those who don’t have religion from those who do.

It’s interesting, the way the novel uses language. To me, sections almost feel like they have been thought out or originally written in an Indian language, maybe Hindi. Do you feel that to be the case? If so, was it in any way deliberate?

Other people have also observed that it often feels like this book was conceived in Hindi and written in English. I didn’t set out to make that happen, except perhaps in some places where the novelist Vishwanath is writing his letters. I think what happened is that I was so submerged in the Hindi and Urdu texts I was dealing with that some of the flavour of their language seeped into my own English prose.

This novel had you, a writer, writing the character of a writer, Vishwanath, who is himself writing letters in first person in the novel. Tell us something about this process of framing the character of a writer in the novel.

I was writing about a milieu that I felt I had no direct claim to, being an English speaker who had not read a single book-length work of literature in any language apart from English till the age of twenty-two or twenty-three. I felt hesitant, like I was an outsider trying to pretend to be someone I was not. When I thought of the character of Vishwanath it freed me to write about that world, a world that Vishwanath could easily claim. Half the Night is Gone is in some ways a book about literature and the role it plays in our lives, the lives of readers and writers. It was also an opportunity for me to pay homage to some of the writers whose works have touched me: Ghalib, Jayadeva, Tulsidas, Muneer Niazi, Parveen Shakir, Krishna Sobti and so many others. In retrospect, it feels like the idea of framing the novel with the life of a writer who maybe writing it was inevitable, but when I first thought of it, it was just a device that helped me get over my block, a device that I borrowed straight from Amritlal Nagar’s Amrit aur Vish.

How much, if at all, does the figure of the reader affect you and your writing process? Do you write books keeping a certain audience in mind?

From the point of accessibility, I do think of the reader, i.e., I don’t want to be overly obscure. But apart from that, I don’t. Every writer is his or her own first reader, and basically, I write to satisfy or edify myself. The next reader is my wife.

For me as a reader, the way the novel is structured and ends, and the way character arcs are framed, some storylines can be continued and explored more. Is a sequel to this book anywhere on the horizon for you?

Yes, it is, but I’m struggling to get it off the ground as of now.

Text Srishti Gupta