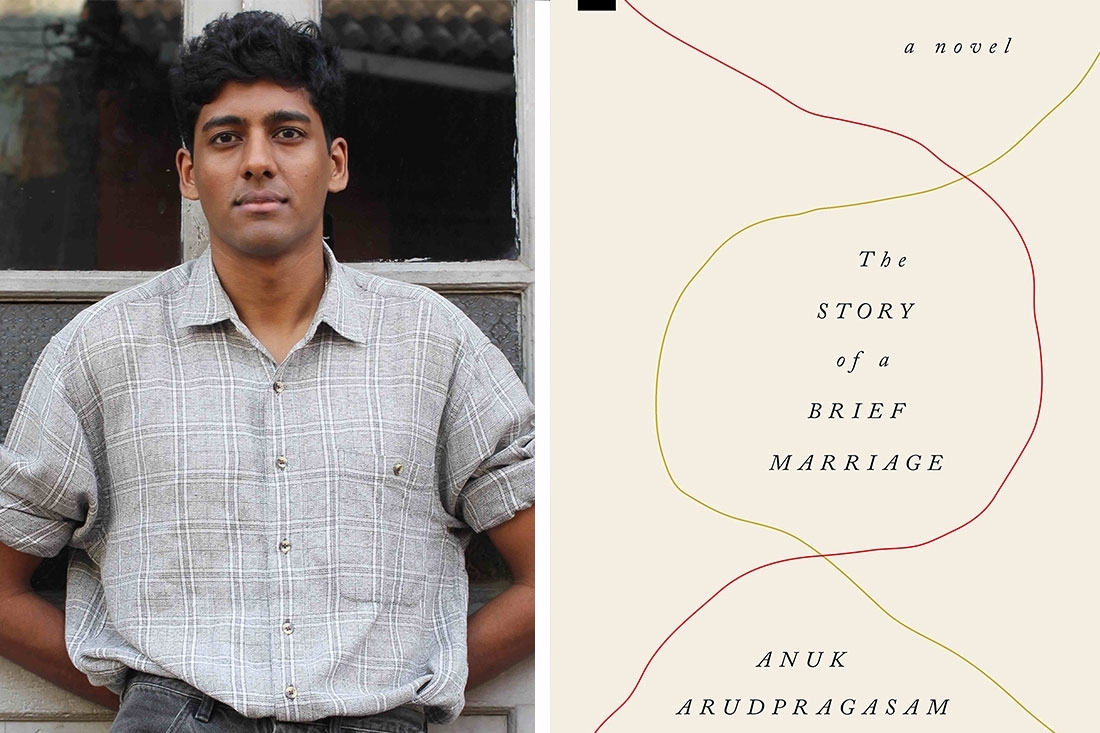

Anuk Arudraprasagam

Anuk Arudraprasagam

Consider this. There’s a bloody war going on in one part of the country, and you’re one of the privileged few to be far removed from it. Would you cross over to the dirty side only to be torn by the tears and trauma if not by bullets and bombing? The winner of the recently announced DSC Prize for South Asian Literature—Anuk Arudraprasagam—did just that, and let the darkness envelope him. I had a long an interesting chat with the Sri Lankan author about his debut award-winning novel, The Story of a Brief Marriage…

Tell me where you come from, and how you began your journey in writing.

I was born in Colombo in Sri Lanka but my family is north of the country, from Jaffna. I grew up in a highly privileged and elitist environment that was far from getting directly affected by the war. In terms of writing, I began at the age of 20. I read a novel called The Man Without Qualities; it is by an Austrian writer from the 30s, Robert Musil… and at the time I was studying philosophy, I was planning my doctorate and I realised while I was interested in philosophy I could pursue more closely the questions I was interested in as a writer of novels than as an academic.

What inspired The Story of a Brief Marriage?

I started writing the novel in 2011. It is set in the last month of the Sri Lankan Civil War in 2009. I guess when the war finished, like most Sri Lankan Tamils I was somewhat ambivalent. On the one hand while I was happy that their wouldn’t be fighting anymore, on the other hand I was kind of worried about the situation of Sri Lankan Tamils now that the government had complete control over the north and east. None of us really knew the circumstances under which the war ended, because the government had banned journalists and independent observers from entering the northeast warzone. That was when all these pictures and videos taken by survivors showed up on the internet and those of us who didn’t live in the north and east came to know better the kind of massacre that took place… 40,000 people died according to a UN report. So the idea was a spontaneous reaction to coming in contact with these images and reports. One of the things that struck me as a Sri Lankan Tamil was, how had I escaped? That’s when you realized how much difference there was between us and people who lived in the war-torn areas… we shared a nationality, a culture and a language but all the trauma they’ve gone through in the war years…looking at their images, hearing them screaming, looking at their dead bodies…there was so much distance and the novel was a spontaneous attempt for me to understand better what happened. To in some way insofar as to bridge that gap, that distance.

Despite this distance, you write in such disturbing detail about the war. How did you reconstruct such vivid imagery?

I don’t really know, we read it and it sounds convincing but it was really an imaginative reconstruction, but insofar as I found out, insofar as any of it is true it comes from the fact that I spent a lot of time in the valley, in northeastern Sri Lanka. I wouldn’t ask people what happened to them as it was a sensitive matter and I didn’t want to impose myself but if somebody in the course of talking to me wanted to share their experiences then I would listen. There were a couple of people who wrote texts, there was a psychiatrist called Daya Somasundaram who wrote a lot of essays from a psychological perspective on trauma in the area, there were lots of interviews with survivors, testimonies, I watched interviews on Tamil TV in South India, but most of all dwelling on these images helped me build the details.

Can you give me a blurb on the book?

The book takes place over the few hours, the eight or nine or 10 hours, in March of 2009. The theme is taken from something that happened earlier in the war, in 1990s in Jaffna, when a lot of parents were worried that their children would be recruited by the LTTE or sexually harassed by government troops so a lot of people married their daughters off to strangers basically feeling that they would not be recruited if they were married and they were less likely to be sexually harassed that way. This is the idea that the novel is taken from. It’s a story of these two extremely traumatized young civilians who have lost many members of their family, who have been moving to escape shelling for months, and are forced to marry each other. It’s a study of trauma and intimacy.

Do they finally find some peace in matrimony?

It’s very difficult to imagine someone enjoying matrimony in such a situation. Matrimony is not really the word…yes they are in some sense married but marriage itself is also a structure and in a situation in which the fabric of the society is being completely destroyed it’s unclear in what sense it’s actually a marriage. It’s more of a façade of a marriage.

Do you think human connections are also, on the other hand, deeper in the face of death and destruction?

Different kinds of humans have different kinds of connections. Some of these connections may be strengthened, some may be changed, some of them may be destroyed in the course of war. Ganga’s father wants her to get married because he doesn’t want responsibility for her. In that sense this father-daughter relationship is destroyed by the things that have happened. On the other hand it’s unclear whether Dinesh and Ganga, the two main characters, can really form a bond. In one sense they have formed a bond in the situation. You could think of the novel as the possibility of all the intimacy between humans in such conditions but so many people were killed, wounded, amputated, it’s difficult to be conventionally hopeful.

Take me through your writing process.

I haven’t ever taken any writing classes. Writing is largely a solitary activity for me as it is for most people, but I also can’t imagine sharing my writing with people when it’s at an early stage. I write at all times of the day. I’m a PhD student at the University of Columbia and I study philosophy but it’s a funded program an it’s seven years long…it’s really just a way for me to devote time and money to writing. I write by hand and I write on my computer. I have a few friends I share my writing with, not many. I usually have a few rituals I engage in before I write—I sweep the floor, I make a cup of tea and once I’m done I leave the house. And I need to have many hours of silence.

Are there any authors you idolise?

I mentioned Robert Musil; there’s a Hungarian writer called Peter Nadas, especially his book called A Book of Memories which is very important for me; then Proust’s In Search of Lost Time; there’s Samuel Beckett, the French novelist Nathalie Sarraute who I really love, and the Brazilian writer from 60s and 70s, Clarice Lispector. I’m a really slow reader and I don’t read much contemporary fiction, but I try to read one novel by a contemporary writer every year in the English language. However, most of the books I read are not written in this decade. I’ve decided to spend more of my time re-reading than reading.

The biggest challenge while writing this book?

Obviously, it’s a very dark subject matter but writing the novel is nothing like going through the situation I was writing about. But because it was so dark, it was something I had to continually go back to everyday and spend several hours with it, and that was straining in some way. And there was a point when I realized I need to finish this as fast as possible and move on from it.

Does your book address the larger problem of war and its repercussions on humanity as well?

There are many different aspects of war that you find in many different contexts, but it doesn’t deal with arming, mobilization or recruitment, it really does deal with civilian, collateral damage. It deals with the violence that is intrinsic to war and its effects on humanity. I’m generally hesitant to jump to broader conclusions or suggest broad implications or political significance. But I’m someone from privileged circumstances and not someone who has suffered directly from war in any way and I’m just trying to understand certain human aspects through the war.

Is there a voice of hope that you mean to give to the world?

Yes there’s some hope in certain forms of intimacy with oneself and others, but there’s also something very devoid of hope about the whole thing. One thing I’d like to say about individuals who’ve undergone such suffering: Some of them are so affected by it that they are scarred permanently and there is no hope for them, they can never escape from this, but there are some people who psychologists call resilient and these people manage to lose a lot and yet leading productive lives.

What is next?

A new novel about desire and yearning. To me the difference between desire and yearning is that yearning is desire without an object. Yearning is a sense of lacking something and wanting something outside of yourself, but without an actual idea of what that thing is. It’s a study of different varieties of yearning.

Text Soumya Mukerji