One of my fondest memories of college is the very first lecture I attended of the paper titled ‘Women’s Writing’. I remember my professor, Dr. Taisha Abraham, a very well-known feminist scholar, introducing us to the mammoth ideological phenomenon called feminism. From Alice Walker to Rasundari Debi, as I took an excursion down the history of feminist literature, I realised that the entire feminist movement thrives on the beauty of its polyphonic nature, seeped in the multitude of socio-cultural experiences. When one looks at just our country, the diversity of feminist literature is immeasurable.

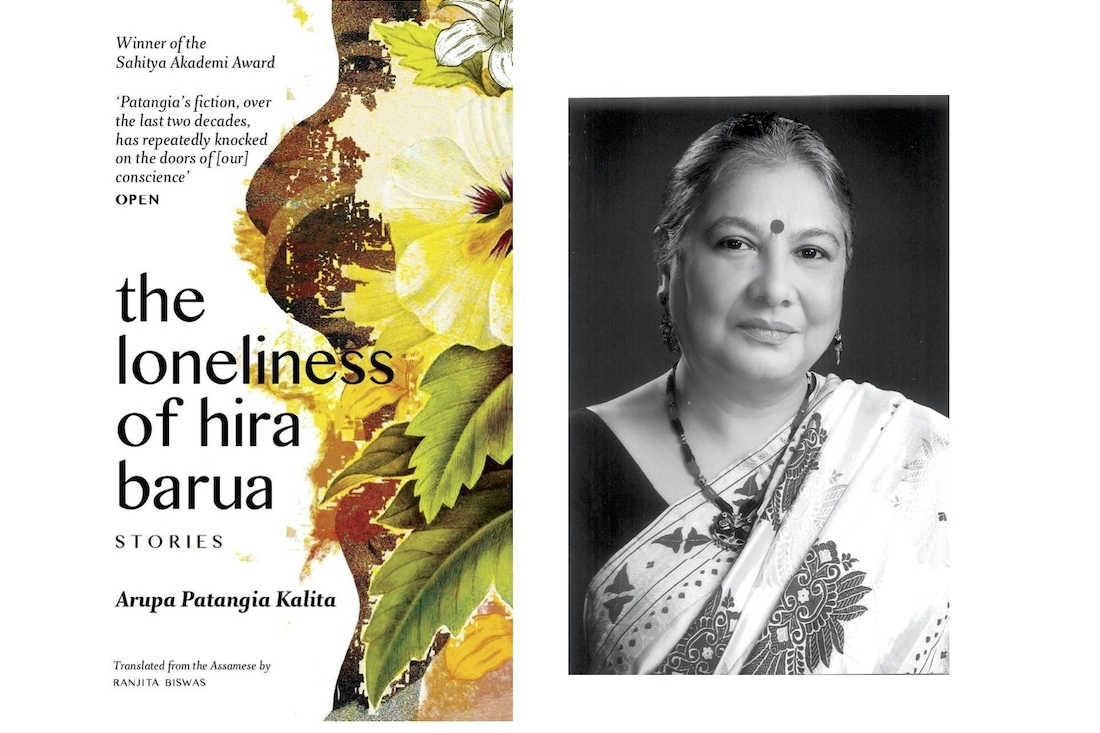

One of Assam’s greatest living writers, Arupa Patangia Kalita's work upholds the spirit of feminist literature produced in our country. Winner of the Sahitya Akademi Award, her book The Loneliness of Hira Barua, is an extraordinary, ever-relevant collection of stories. They present piercing, intimate portraits of women navigating family, violence, trauma, ambition and domesticity with caution, grace and a quiet resilience. In the recently released, wonderful English translation by Ranjita Biswas, Arupa Patangia Kalita’s powerful voice is brought to fresh and vivid life. Written in a variety of styles, from gritty social realism, folklore to magical realism, The Loneliness of Hira Barua is a modern classic of Indian literature. We connected with the author to know more about her literature.

What led you towards writing and how has your craft evolved over the years?

I was born and brought up in Golaghat — a small town with a rich cultural heritage amidst verdant beauty of nature. I had a creative and happy childhood. Books were my constant companion. Those were not the days of television or smart-phones. I read voraciously, wrote little pieces of stories in the children corners of newspapers. I grew up listening to tales from my great grandmother and grandmother. In my school I learnt English and Assamese. I write in Assamese because English is a language I had to acquire, Assamese is a language I was born into. My first published short story was about an eleven-year-old maid servant with whom I had developed a sort of friendship, who could not visit her home during the Bihu festival because of some emergency. Even then the sufferings of the poor and the neglected saddened me a lot. I was a student during the seventies of the last century. That was the decade of protest, rebellion and hope for a new world. Those highly formative years are influencing me even today.

What do I write? I write what I see around me, about the air I breathe, the water I drink, the river I see, the flowers I smell, the times where I stand, the folk tradition in which I grew up, the history that I live in. Tools to interpret and understand the reality around me range from oral literature to cinema, painting, poetry, to politics and history. I use a variety of form — content determines my form. Over the years I have dealt with different content, and accordingly have chosen forms that the content demanded — from stark naturalist documentation to fantasy, may be even magic realist techniques. I don’t adhere to any particular form, though broadly speaking, the forms I use are variations of realism.

After so many years as a writer, how would define your relationship with writing as now?

I am a writer trying to interpret and portray reality. My perception of reality is a politically conscious writer’s perception of reality. I have seen how common people, for no fault of theirs, have been caught in the labyrinth of history. I wish I could be the voice of these voiceless people. Another point — I am a woman, and being a woman in this country, how can I not write about women? Personally I am one of the fortunate women. My parents and my family have contributed immensely in protecting me from patriarchy, and in my journey as a writer. That is why I see the picture much more clearly than many other women who have internalised the values upheld by patriarchy. Though things are changing gradually, women in our country have a long way to go for achieving a dignified human identity.

I consider writing to be a social activity, and in that sense I am also kind of a social activist. I try to understand the dynamics of society, and try to feel the changing, emerging reality underneath the surface reality of the present.

What inspired the stories in The Loneliness of Hira Baruah?

In The Loneliness of Hira Baruah, there are fourteen or so women characters. These characters have to face and tackle daunting challenges in life. I have seen from close quarters how women are thrown away like garbage, oppressed, marginalised, rejected, and how they suffer immensely in situations for which they are not responsible. Silently, they bear the unbearable and to my awe, how vigorously they assert life despite the brutal times. I have tried to be their storyteller. Positioning of patriarchy in these stories is not limited to the unequal power relations between woman and man, but it extends to the power relations between woman and overwhelming socio-political forces. Some of my stories are comments on and protests against meaningless, mindless violence.

How have your roots influenced the stories in the book?

My roots in Assam have surely influenced me as a writer. I have benefited from the rich folk tradition of Assam. I have used extensively, folk elements in my works. The spell binding beauty of nature in Assam forms the back drop of my writings. We have quite a number of tribes in Assam, each one with its rich cultural tradition — folklores, folk songs, dances and rituals. I have used these elements extensively in my writings to bring out the deeper layers of the social psyche. They are not mere embellishments. And the political turmoils in the state have hardly any parallel anywhere in present day India. Living in Assam, one can hardly ignore these realities, especially when one is a politically conscious writer.

Could you tell us a little bit about what your creative process was like behind writing the book?

For me writing is a social activity. I feel responsible to speak for the suffering people. I take up stories of people whose cries of agony don’t reach the ears of the captains of society. Have you ever heard a story like that of Suwagmoni’s mother whose child was killed in the Dhemaji bomb blast? Or for that matter the story of Mainao? Time has not been kind to us in Assam. I have tried to capture the stories of the unrelentingly adverse time in my stories.

Your book is immensely important today, especially in terms of the political and feminist connotations of the stories. What do you hope the readers take away from the book?

In these stories I have tried to bring forth the sufferings of women in circumstances over which they have little control. Women are the worst sufferers in any crisis in society, be it wars, riots or simple and plain economic disasters and the like. I want the reader to be sensitive to this reality. When will women enjoy dignity as full and perfect human beings? Pages of the book are replete with a host of negative words like rape, murder, arson ,violence, sadness, helplessness, loneliness — in short, an atmosphere of all pervading gloom. I want the readers to ponder over these questions and identify the forces that are responsible for this gloom and negativity.

How have you been coping with the pandemic and what will be the new normal for you post it?

Coping with the pandemic has been painful.The pandemic has brought to the fore the inadequacies of the system. Peasants, workers and the middle class have been the worst hit. The sudden lockdown was a thoughtless, whimsical decision, resulting in extreme sufferings for the common people. I have no idea when we could be free from the menace of this pandemic called Covid 19. What I gather from the opinions of experts is that we must learn to live with this nuisance, with our faces masked, our hands washed all the time, sanitisers in our pockets and hand bags. If that is the scenario, if that is the new normal, then I see no reason why lockdown should extend any longer. Now the government must see to it that the toiling masses could get back to earning their bread, if not the butter. The government must see to it that when a decision is taken, some thought is given to how the decision might affect the lives of the masses of the people.

As for me, I am trying to find out how the people have responded to the crisis, how they are trying to mend their broken dreams, and against all odds, dreaming new dreams.

Lastly, what are you working on next?

Writing a novel about a courageous and exceptional woman, a tea-garden worker who joined the freedom struggle and subsequently was shot dead by British tea planters. Half way through it. Hope to finish the novel this year itself, the year of the pandemic. Let’s hope 2021 will not continue to be shadowed by Corona.

Text Nidhi Verma