Photography by Rohit Chawla

Photography by Rohit Chawla

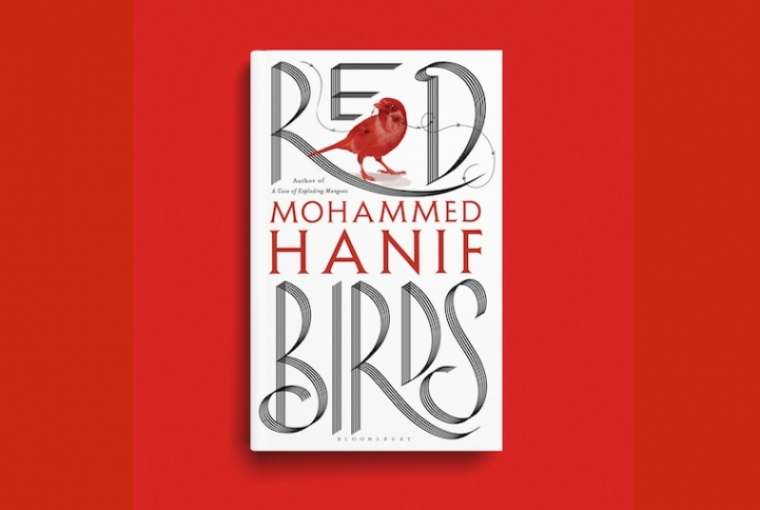

An award-winning novelist, journalist and playwright for over fifteen years has one big fear that no expertise can cure—the blank screen. That, of course, is Mohammed Hanif’s biggest joy too, for it has been won over a village childhood with little opportunity and a trying youth as a military pilot. After giving us delightful novels such as A Case of Exploding Mangoes and Our Lady of Alice Bhatti and aside from his new novel, this blank slate though scary allows him to start over and over again on new things such as writing now in his part mother tongue, Punjabi. The British-Pakistani author, who started his journey with Urdu writing and went on to woo the English-speaking world, shares his journey across language and lands while writing Red Birds, a powerful and timely story about war, family and love.

What is your first memory of writing?

Writing an essay called ‘Our Cow’ in primary school.

How have your growing up years in Okara, Pakistan, and your family influenced the writer you are today?

I don’t quite know how but I am sure it has influenced me more than anything else. There was a lot of oral storytelling around. It was called a baat, hamaiNbaatsunao. There were bed time stories which were usually improvised by mothers and grandmothers and uncles. And people on the street corners turned their trip to Lahore into an adventure story, and someone turned their struggle to buy a cinema ticket on Eid day into a thriller.

So more than books, it’s the oral tradition. Then there were professional, travelling storytellers. And children were asked to leave before they started their late night, more risque folk tales, and one hid in a corner and listened. And then aphrodisiac sellers, and ice qulfi sellers, and snake charmers, they were all expected to tell a little story. People sold printed stories in buses, reciting them, then leaving it at a cliff hanger and asking you to buy it. So I think that tradition has influenced me more than real books.

Looking back at your journey, how would you sum up the last 15 years of your writing practice? How has your craft evolved over the years?

I don’t know if it’s evolved but I have accepted that it’ll always be a struggle with lots of blank spaces and then something will just make you start scribbling again. I try to set targets and always fail. About 15 years ago, I started writing in Urdu which was fun in the beginning; you could show off your knowledge of obscure Urdu references, quote Iqbal and Ghalib. Recently I have started writing and broadcasting in Punjabi and again, it’s very exciting. I am writing a language that I have spoken every day of my life, but for the first time I am able to communicate as a journalist and writer. So I was visiting my hometown last month and my family and friends, who have never read anything by me, were quoting from my Punjabi articles which was a bit freaky but nice.

What inspired Red Birds?

A string of personal losses. Very deep, very personal losses. I am just going through the copy edits for Red Birds and it takes me a while to talk about the book after I have finished it. At the moment it seems too personal, my feelings about it too raw, ghosts of my characters still hovering over my writing desk. I hope I’ll be able to talk about it after it’s out.

Your writing is characterised by dark humour, faith in humanity and most of all, the telling of truth. Do you think these are your responsibilities to the reader—especially the truth?

Well I have never heard anybody say, look I am a big liar. When you ask people in job interviews what’s your weakness, the most common answer is ‘I can’t lie’. Which is an obvious lie. Most people’s CVs are little pieces of fiction. When I am doing journalism, there is a certain responsibility to tell the truth, or at least write about things that you think are urgent, also things you feel other people are not talking about. So you are drawing attention to an aspect of reality that others might want to ignore. In fiction it’s different, it’s more playful, or at least it should be. You are saying, come here, I want to tell you a 300-page long lie, but I am hoping you’ll find your own truth in it.

Take me behind your creative process. Does it usually differ for stage, film and radio?

It’s collaborative in all three mediums you mention. You don’t write a film or a play or an opera in isolation. Someone wants you to do it. They have ideas and you have some ideas. When the collaboration works, it’s the most beautiful thing in the world; when it doesn’t you can always blame the other person. As for writing novels, you are on your own for a very, very long time. Your editor doesn’t get to see anything till you are almost done.

We live in politically volatile times. Have you ever felt your writing affected by its workings?

I have lived long enough to know that there were no times that were not politically volatile. The 80s were pretty vile, 90s were pretty f**ked up and the rest, we remember as politically volatile. Every word I write is affected by how the world works, what it does to us, to our fellow human beings. Also what we do to the world.

What has been your biggest challenge thus far?

Feeding a toddler, putting him to sleep. Getting him off the computer. Making sure he doesn’t bang the door on his hand or fall off a balcony.

Has there ever been a high or low point in your life that ended up being one of your deepest inspirations or gave you a great story?

Every day, staring at a blank page is the lowest point of my life. Inspiration happens once or twice a year. It doesn’t usually come from a high or low point, it comes from ordinary moments in life, like crossing a Karachi road without getting run over or when you can make a roti without burning it.

Who are some of your favourite authors and those that you see promising from the younger lot?

Julien Colmeau, a Frenchman who writes staggeringly good short stories in Urdu and Punjabi. Saba Imtiaz. Omar Shahid Hamid. Ali Akbar Natiq. Kashif Raza. Sanam Maher, who has two books coming out this year. Many others I can’t remember right now.

What is next from here?

I have collaborated on an opera called Bhutto which opens next year. Besides that another book, another rant in Urdu, another in Punjabi.

TEXT Soumya Mukerji