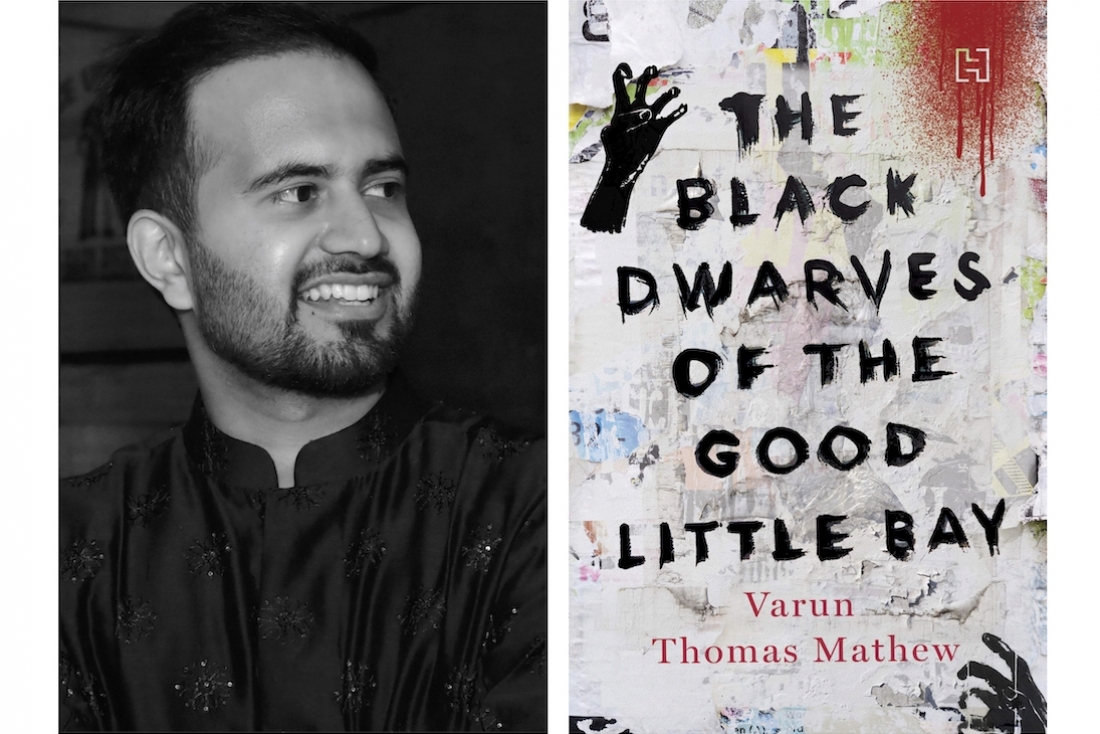

Varun Thomas Mathew’s debut book, The Black Dwarves of the Good Little Bay, attempts to look back at everything humanity has lost by fictionally depicting the future of the city Bombay. The sea has invaded its boundaries and its inhabitants reside in a towering structure called the Bombadrome, which hovers above the barren land. Theirs is an artificially equated society; they lead technologically directed lives; they have no memory of the past. They don't remember that this place was once called Bom Bahia, or Bombay, or Mumbai. One man, the last civil servant of the India of old, finally decides to speak up and remind the people of what happened all those years ago, of the events that unmade the city, then the nation, and finally their lives . . . Sharp, layered and scathing, The Black Dwarves of the Good Little Bay will grab you by the scruff of your neck and force you to listen.

We connected with the author to know more about him and his debut book.

Tell us a little bit about yourself and how you were lead to pursue writing.

Being a lawyer, it kind of feels like I’ve always been writing… though, of course, briefs and contracts aren’t quite the same as fiction!

I had a fairly sedate, regular upbringing as a child. So much of the excitement I derived came from fiction – in fact, schools in those days had a library hour three times a week when you could read whatever you wanted, and my school library had a lot of great science fiction and fantasy.

Writing also became a way of preserving things or emotions that no longer exist. For instance, no one who lives in Bangalore today can understand what it was like to grow up in that city – an adolescent city almost, encouraging of almost any sort of expression and strangeness. No one who started watching cricket in the last five years can understand what it was like to hope against hope for a miracle from a team that was a metaphor for you – the underdog. These things aren’t reflected in typical history, and fiction seemed to be the only medium of recording this.

What inspired your debut book, The Black Dwarves of the Good Little Bay?

Before the last general elections, I met a lot of people who told me that they would vote into power anyone who could usher in economic prosperity, no matter if they had a chequered past when it came to human rights or protecting the constitution. It was as if building a 1000 roads was adequate penance for a riot.

I’m not expressing judgement on this view, but this question – of whether economic development could atone for past sins – became a sort of constant undercurrent of those times. It formed the basis of why I began to write Black Dwarves.

Then, our country began to change dramatically post 2014. Gunter Grass once said (and I paraphrase) that he wrote The Tin Drum primarily because he wanted to capture the essence of those times for future generations. In a similar vein, I wanted to (or at least try to) do the same with these times for India – an era of change for who we are as a people.

Can you give me a blurb on the book in your own words?

It’s difficult to summarise everything in a single para, but here goes:

The Black Dwarves of the Good Little Bay is, in some ways, a book about regret. Regret over the loss of a city and a way of life; regret for past choices that were made collectively as a people; regret about personal failures, that every citizen should have if they let terrible things happen in their country without trying to do something about it. It’s also a book about nostalgia, given that it’s set in the near future (2040), but looks back at our current times and extols the wonderful, magical things that don’t exist anymore. It’s a book about absurdity, and how weird we are as a people – in terms of the things we love and hate, the things we preserve and destroy, and the things we choose to laugh over and kill over.

The book is a rather necessary look at everything this country has lost in these past years to become what it is today. What was the creative process behind the writing of this book?

Practicing the law was a huge boon. It gives you an insight into aspects of other people’s lives in a way that few other professions afford – you get to see injustices, inequalities, despair up close, and over time, all of this adds up to give you a fundamental sense of the problems of our country.

Also, I’ve always loved the way the Latin American masters… like Alejo Carpentier and Garcia Marquez… blended history and fiction to create such exquisite, moving portrayals of their land and times. So part of my process was to follow the issues that I was raising in Black Dwarves and tie them in with our national history and social past. This involved a vast amount of research – I even spent a lot of time reading newspapers that were decades old.

There was also dealing with a sense of hopelessness – the kind of despair you feel when you wake up and see lynching and rape on the front page of your newspaper – which seeped into my writing.

I think what I enjoyed the most were the magical realism parts, where I could let my imagination romp. To create the Bombadrome, and simultaneously re-imagine the old Bombay, was a lot of fun.

What kind of challenges did you face while writing this book?

Getting the voices of each of my characters just right, given all of their differences, was quite challenging.

Also, being able to adequately capture Mumbai in the past tense, while looking back from forty years in the future at a time when the city no longer exists.

Lastly, keeping the part about the elections authentic. An election in India is the most complex movement of people, capital, and ideas, in the world – and I wanted to do justice to that process. It helped that I worked extensively on the 2019 election.

What do you wish the reader takes away from your work?

I’d want my readers to take a million things away from this book! But wishful thinking aside, if I had to boil it down to just two things, it would be these:

The fact that there is a magic about our cities, as they exist now, which is slowly being lost. This magic is vast just as it is simple - it ranges from things like how the monsoon clouds roll in, to how a single street can encapsulate the culinary delights of 1 billion people over a thousand years. If people fight to retain this magic, then perhaps its disappearance will slow down.

The worth of a vote. There are consequences to our electoral choices that live on for generations after we are gone, and this needs to weigh in our choices before we get our fingers inked.

Lastly, what’s next?

My writing is deeply influenced by the city I’m living in at the time, and currently, I’m falling in love with Delhi. I’m working on a second book set in Delhi, and I hope to be done by mid- next year.

Text Nidhi Verma