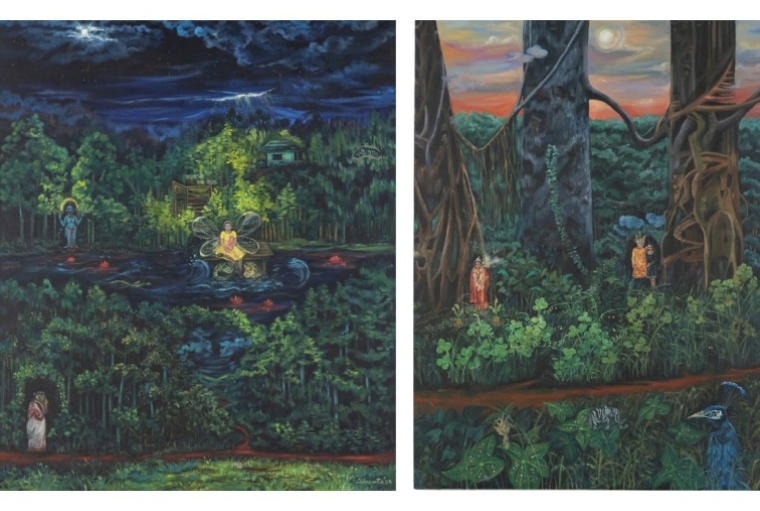

That Night, A Forest Grew, 2022, Oil on Canvas, W 60 x H 42 inches

That Night, A Forest Grew, 2022, Oil on Canvas, W 60 x H 42 inches

Debosmita Samanta’s art takes us on a personal yet universal journey through memory, tradition, and the untold stories of women. In her latest exhibition Bariwali, Samanta explores the role of women within the confines of familial and cultural spaces, drawing deeply from her own Bengali heritage and personal experiences. The title Bariwali translates to 'lady who owns the land,' reflecting not just the concept of home but the powerful, often invisible women who uphold familial and cultural legacies. The exhibition is rooted in the themes of memory-keeping and the rituals of daily life, inspired by the women in Samanta’s family, particularly her grandmother, who serves as the primary muse for many of the pieces.

A Word In Private, 2023, Oil on Canvas, W 30 x H 30 inches

Tell me about your journey as an artist. What made you, you know, what are your first memories of painting and how did you get into it?

My first painting was a house and countryside when I was a child. Looking at it, I think that the idea of home and nature, and the lady, it all seems to have been decided early on. It’s been a long journey—there have been ups and downs. Conceptually, it also took me a long time to develop. The idea of including nature in my work started in 2013, and that too was due to a personal loss in life. But over time, things evolved—things became more research-based. Whenever I went home, I talked to my parents, especially my grandmothers and my mother, and I also went around observing people. Since I am a memory keeper, I either keep memories in physical form or in written form. These things played a very important role in developing the artist I am today. Of course, observation has been a very big part of it.

Stay In Memory - 1, 2024, Oil on Canvas, W 40 x H 30 inches

How did you arrive at the concept of Bariwali?

The word Bari means 'home in Bengali. The term Bariwali can be translated as 'landlady' in English, similar to 'landlord,' but in my work, it refers to the woman who owns the land. In my paintings, there is typically one or two female figures who serve as the central narrators of the story. These women are the pillars of my work, and they represent an essential aspect of my life—they are the ones telling the story.

Most of my paintings are inspired by my family members, particularly the women, with my grandmother being the primary reference. The relationship I developed with her over time made me realize that she embodied the concept of Bariwali. She was someone who held onto so much—traditions, rituals, meaningful relationships, and stories. She had a reason for everything. For me, she is the perfect Bariwali. However, I don’t want to limit the concept to just one individual. In all my paintings, there is always one female figure who narrates the story, embodying the essence of Bariwali.

The Lullaby Land, 2023, Oil on Canvas, W 57 x H 31 inches

I’ve noticed a recurring red stream, almost like a river, in many of your paintings. What does it symbolize, and why do you include it in your work?

While Bariwali refers to the idea of home, there’s also the recurring imagery of roads in my paintings. The lines you see are roads, which started appearing in my work around 2019. Initially, these roads symbolized the path that connected me to my hometown, my village house. Over time, however, the lines evolved—growing darker, deeper, and eventually becoming red.

The color red carries significant meaning in Indian culture, particularly vermilion. These red lines are more than just visual elements—they represent bloodlines that connect me to my ancestors, my roots, and my culture. They are like a family tree, intertwining personal and cultural histories.

Your paintings often depict domestic chores and social scenarios. What do you think these scenes reveal about the role of women within the family?

I grew up in a middle-class family, with several other families living together in a small space. I observed women spending most of their time indoors, handling household chores and interacting with children, in-laws, or husbands. These tasks were always done with a deep sense of commitment. I never saw an attitude of reluctance or exhaustion; they were simply part of daily life.

Even today, when I visit my village house, I see the same women performing these tasks without change. It’s as if these responsibilities are handed down and remain unchanged over time. While the nature of these duties may have evolved, the fundamental roles of women within the family haven’t changed much. For me, these observations are raw, real experiences. Growing up, my grandmother didn’t tell us fairy tales—instead, she shared her life stories, the struggles she faced, and taught us practical skills, like how to cook. These are the teachings that shaped me. I find that these ordinary, often overlooked details of life are worth capturing. Women’s private moments, like gathering to talk in secret, are so commonplace that they often go unnoticed. Yet, these are the moments that inspire much of my work.

Paths On Water, 2024, Oil on Canvas, W 30 x H 36 inches (left) | Nice to Meet You, 2024 Oil on Canvas, W 36 x H48 inches (right)

What kind of message or feeling do you hope to evoke in viewers when they encounter your work?

The message that seems to resonate with viewers is a sense of emotional connection. I’m a Bengali from a small town in West Bengal, now living in Hyderabad. My show is happening in Mumbai, which marks an entire journey. What strikes me is how common the themes in my work are. When people see my paintings, they often say, 'I’ve seen this before. I’ve seen these women.' There’s an immediate emotional connection, and I think that’s powerful.

The work explores themes of being grounded in one’s roots, acknowledging one’s past, and recognizing the importance of family and ancestry. These are universal truths, and I find that viewers from various backgrounds are able to relate to these themes, regardless of their specific cultural context. Whether they are in their 20s, 40s, or 50s, people are able to connect with the emotional core of the work, whether it’s a mother and child, or a group of women sharing a private moment. I think the work is resonating with viewers because it taps into these common human experiences

Faded Memories, 2023 (left) | Fragments from the Garden, 2018 (right)

Your paintings often appear set in expansive, green spaces—like forests. Do you use these elements to symbolize a mental escape from confinement or to explore emotional and psychological landscapes?

I don’t refer to these settings as landscapes; I call them mindscapes because they are spaces I create in my mind, not tied to any specific physical location. The greenery in my work is a direct reference to my childhood in my hometown, where there were lush green surroundings and ponds. My grandfather was passionate about gardening, and I too have always had a deep connection with nature.

Nature has always seemed bigger than us, and I believe it plays an important role in the mental escape I try to express. Women of my grandmother’s generation, for example, had no concept of going out for relaxation. They were content within the confines of their home, doing the same tasks every day. There was no escape for them, and that feeling of confinement is something I’ve tried to express through my work.

By placing these figures in mindscapes, I want to give them the freedom they lacked in real life. These spaces are boundless, without walls or boundaries, offering a sense of freedom and openness that contrasts with the physical limitations they experienced. While I call them mindscapes, there are elements in my paintings, such as a window or a calendar, which ground the work in specific memories—like the house where I grew up or the passage of time. These elements serve as reminders of the emotional and psychological landscapes of my past.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 18.11.2024