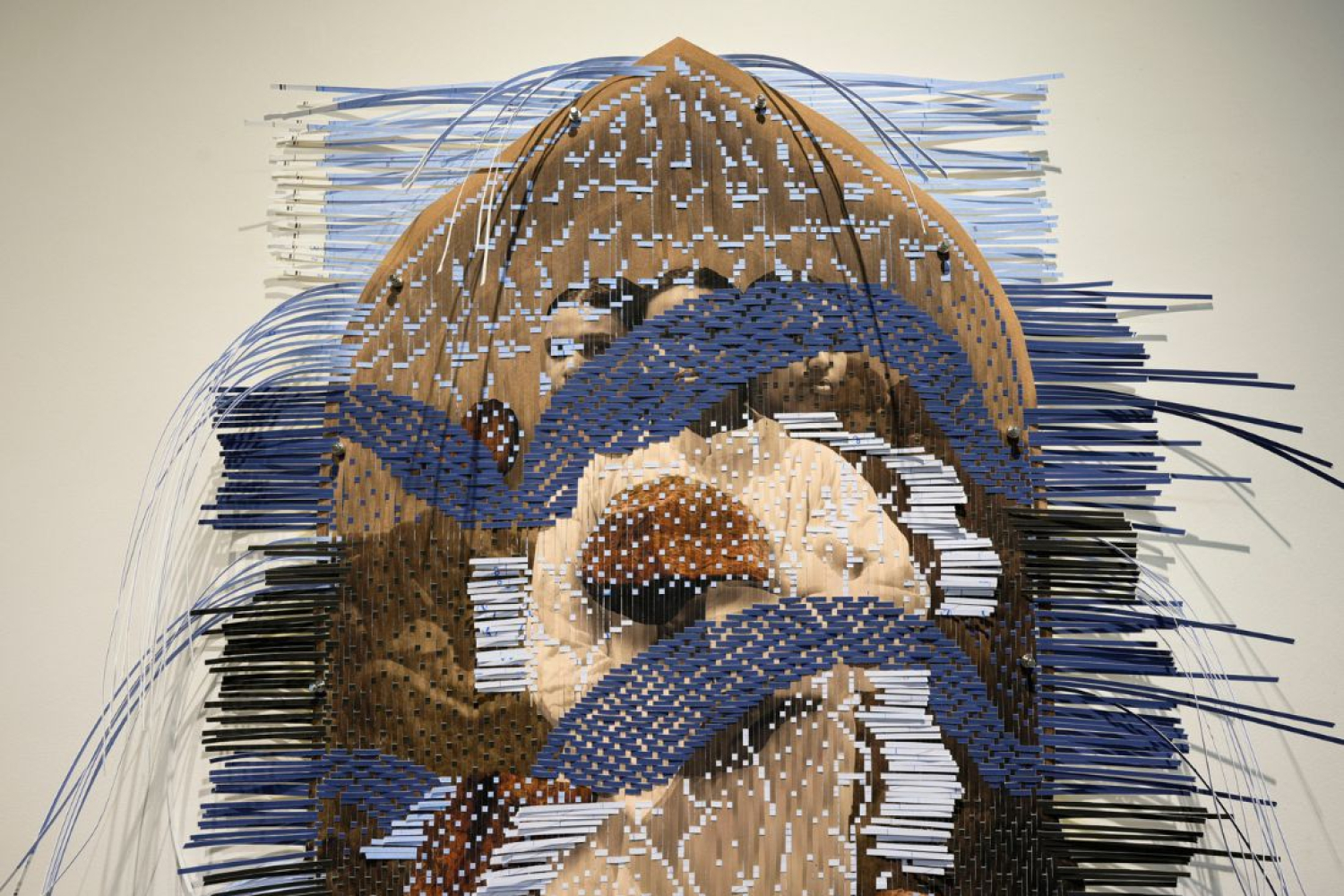

Dendritic Data I 2024, Paper weaving, Archival print on Photo Rag paper 100% cotton 310 gsm

Dendritic Data I 2024, Paper weaving, Archival print on Photo Rag paper 100% cotton 310 gsm

"Many lines and borders may be drawn, but it can never set people free of their reminiscences, free of their associations, free of the love and the sense of belongingness for their place of birth.” — The Shadow Lines, Amitav Ghosh

In 2021, 74 years after the Partition of India, artist Arpita Akhanda tattooed two scars on both of her arms in a performative art video, The Living Scars. The dissected lines of India and Bangladesh are being imprinted on each arm. The performance marked the significance of August 17th, 1947, the day when the Radcliffe Line was officially announced. The Living Scars turns Akhanda’s body into a sight of Partition that her grandparents went through. She tells us more about it, “I wrote a letter to my body before getting the mark and after getting the mark, what happens to the body and how do I look at these two marks now being there on my body permanently. How would it feel when a day before you know you are free and a day after you don't know if a line can cross your dining table and your house is divided into two. I call them [the tattoos] scars and experience how it feels to live between these two marks, like the way we live in a country between two waters.” This performance permanently associates her body to the demarcations of 1947—in a sense, never setting her free from the love and belongingness of the land of her ancestral history.

The living scar 2021 Screenshot from Performance video

Akhanda grew up in a family of artists who had migrated from Bangladesh during the partition and moved to various locations in India before finally settling in Cuttack, Odisha. The idea of migration was instilled in her being and consequently in her artworks. Every time her family moved in India, there was a specific space or wall in the house dedicated to their memories of migration with photographs, albums, textiles and objects. She narrates, “I would be very interested, as a child, to understand why we had such spaces. The earliest memory that I have of getting into these narratives was when I was in grade two or three and my friend was going to her village for summer vacation and she asked me if I was going to my village. I had no answer to that. I came back home, I asked my father where is our village? So he redirected the question to my grandfather, to which he said that we don't have a village anymore. And I was too young to understand the idea of the term ‘anymore’ but it opened up the conversation between me and my grandparents.” Soon, she realised that those photo albums, poems, diaries and objects became an idea of home for her grandfather, a legacy he passed on to her father and then to her.

Dendritic Data I 2024, Paper weaving, Archival print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag paper 100% cotton 310 gsm, 69 x 46 inches approx. each (set of 3)

After studying art at Santiniketan, Akhanda started reliving the past of her family through art. She realised that in her heart she’s a memory collector, more than an artist. In 2015, when she was wondering on how to carry the memory of independence or partition in her body through intergenerational passage, she recalled the political and personal instance of her grandfather giving away the clothes he was wearing to the river as a form of rejection to this new idea of freedom. On 15th August that year, she performed the same to relive the personal memory of partition. She further explains “ the inclusion of water body as a metaphor for transit and settlement both and the in-betweenness that a migrant body feels.” From there, she again started going back to the archives of her family and her father gave her a diary of her grandfather where he's writing the questions and answering himself.

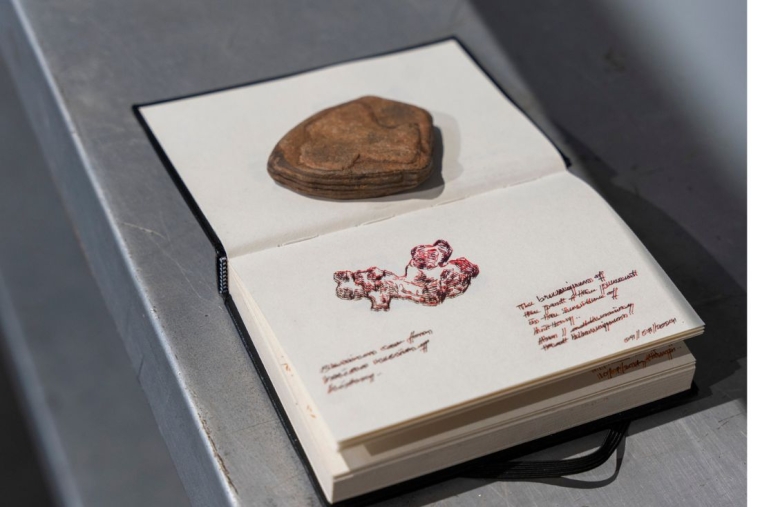

In 2018, she got an opportunity to go to Bangladesh for a performance and ended up going to her village with her family, sinking in everything about her ancestors’ land. This visit created a whole new artistic era for her. She expresses “Something changed, all these stories and memories became evidence at this very point. I was thinking, how do I work with this kind of a personal history that often gets diluted or erased inside the larger historical context? How do I look at this photo album now? Till now, they were just photographs. And now it holds so much more than just the photographs of these people. So I started to bring weaving as a language in my work, where I was looking at the warp as the past and the weft as the present or the warp as a personal memory and the weft as a larger historical memory to bring them together to create a third narrative where they both live together and plays hide and seek like the kind of hide and seek the history plays in personal and historical archives.” With these old photographs, she weaves together the past and the present with papers into a third space that preserves the historical archives of her land and her family.

360 minutes of requiem 2022, 3 hours, 2 days Performed at The studio, India Art Fair Grounds

In 2022, she also performed 360 Minutes of Requiem at the India Art Fair, where she tried to untie a 360 feet barbed wire for three hours for two days as a metaphor to break the borders that dissect our lands. She further explains, “by the end of the performance, I gave away the open barbed wire to my viewers as a token of remembrance of their participation in the performance. It was also very interesting that after the performance, I lost my fingerprints because the thumb is the section where you put the most pressure to open the barbed wire and while doing that I lost my fingerprints for a month almost. So it was interesting for me to see how I lost my identity also as fingerprints are considered a tool to identify in the process.

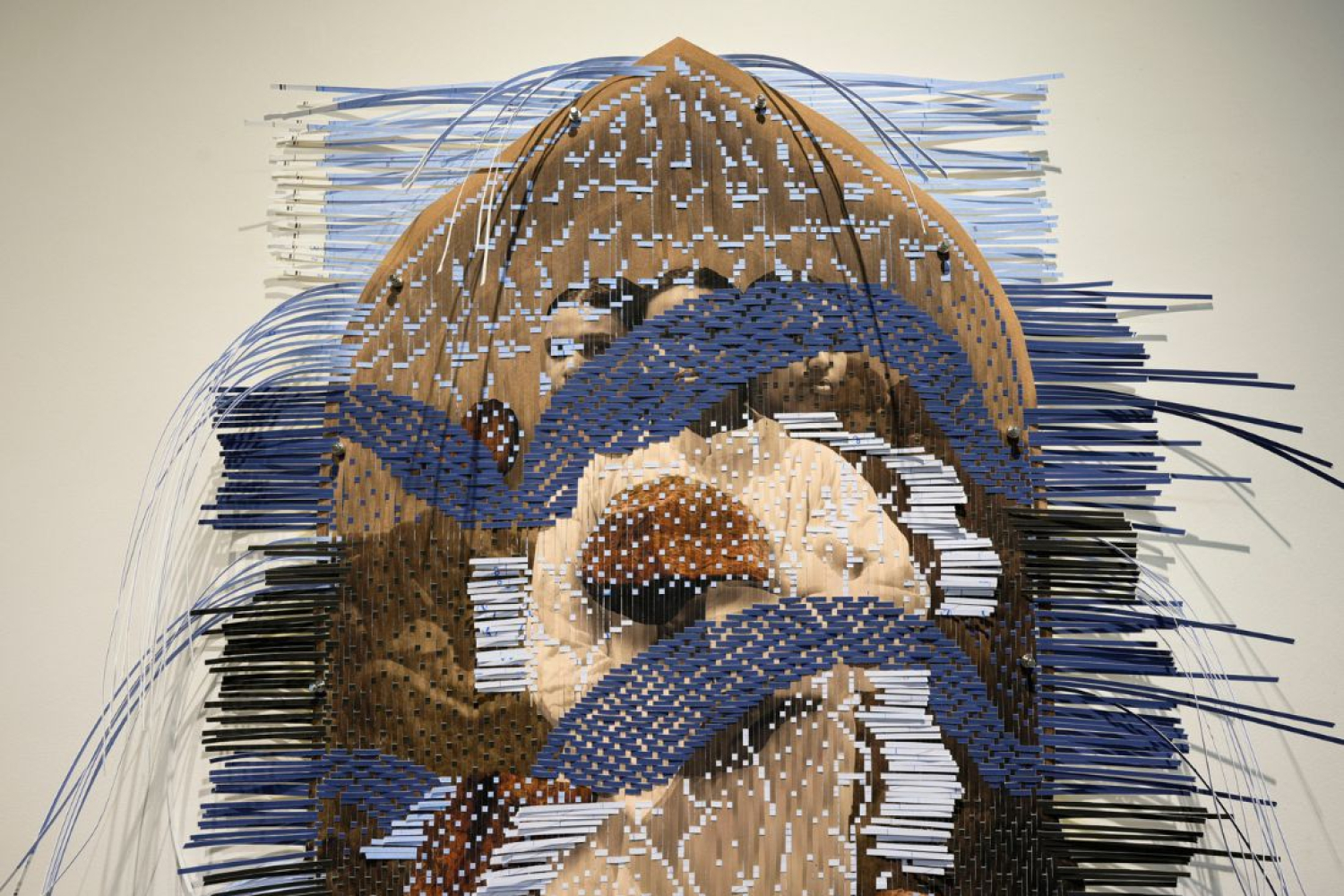

Fragmented Continuum Installation, 2024, Pen and ink drawing on drawing diary

Currently at an artist residency in Hampi Art Labs, Akhanda is collaborating with local weaving communities who repurpose plastics. She explains, “I find it intriguing to use this material for documentation and archiving, especially as it reflects the ruins of our time. I’m translating these plastics into art, exploring their significance in our contemporary context.” She also made a series of sculptures using rocks she gathered, which she turned into stamps, viewing them as the sediments of history from the nearby Tungabhadra river.

I am not a refugee I, 2023, Paper weaving, Archival print on Innova smooth cotton high white 100% cotton 315 gsm

Through Akhanda’s attempt of transcending the borders created by men, I am reminded of Amitav Ghosh’s definition of borders as shadow lines. The shadows lack clarity or physical markers. They are vague and intangible. Similarly, Ghosh asserts that the borders that separate nations are nothing more than artificial lines created by men. As Ghosh again says in his novel, “In the shadow lines, borders become porous, allowing us to explore the depths of our shared humanity.” Akhanda pins down these shadow lines and allows the shared humanity of the both sides of fences, the past and the present to deepen our understanding of the effects of borders through a personal lens.