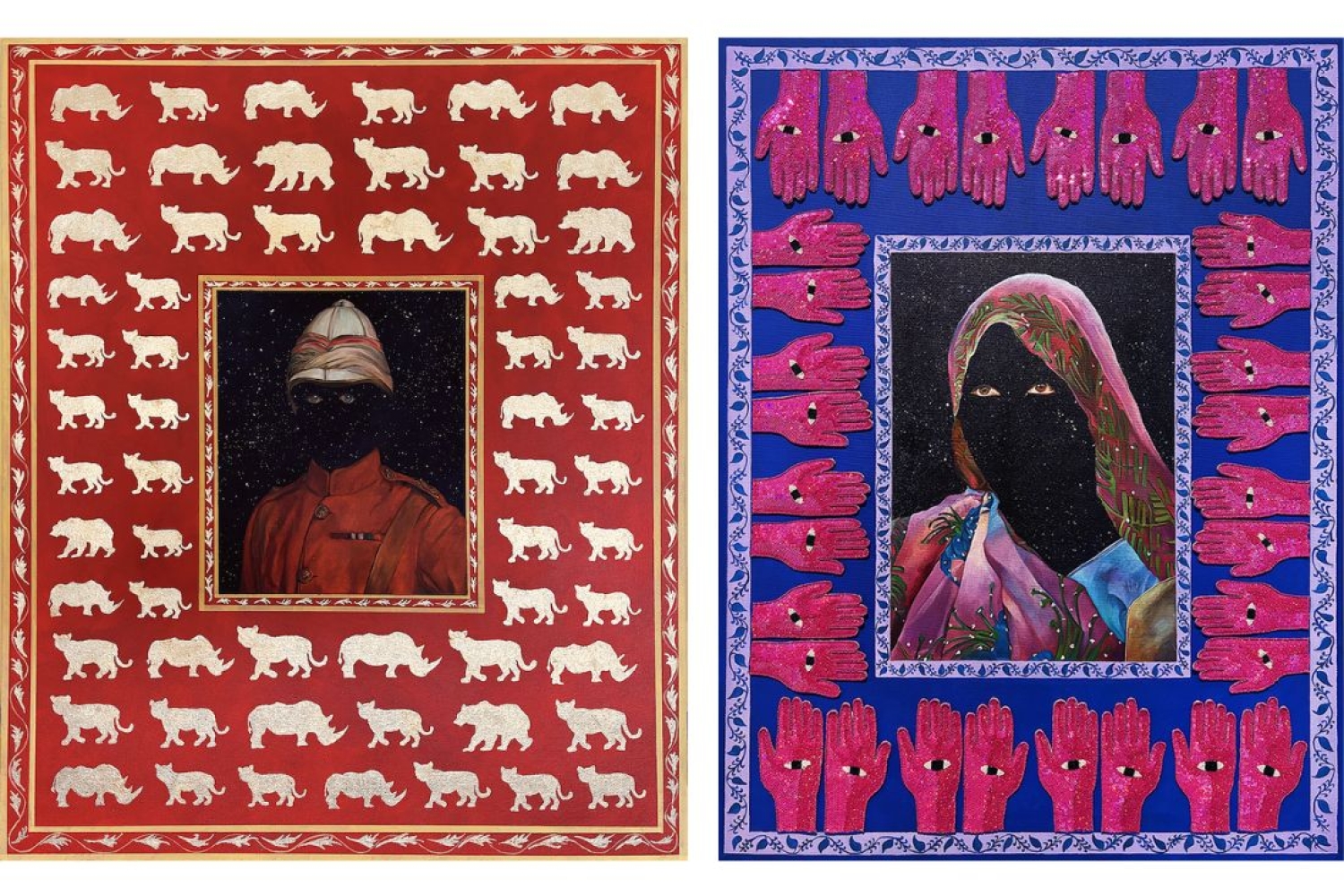

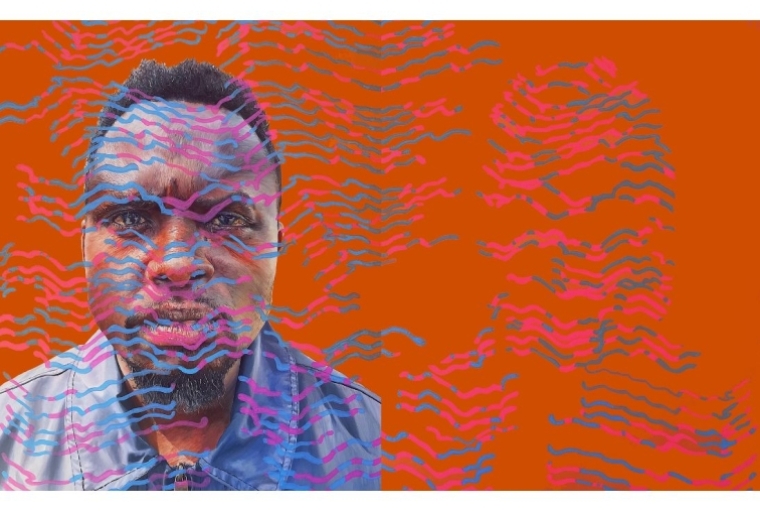

George's Big Day Out (left) | A Fly in the Milk II (right)

George's Big Day Out (left) | A Fly in the Milk II (right)

Kennedy Prize winner Sid Pattni's art travels across the themes of identity, migration, and the complex legacies of colonialism. His practice is a meditation on the tensions and nuances that arise from navigating multiple cultural histories—particularly the intersections between his Indian heritage and Australian upbringing. With a keen interest in visual language, Sid’s works incorporate diverse mediums and techniques, but one of the most striking features of his art is his use of embroidery. This tactile, intimate medium allows him to stitch together fragmented memories and cultural narratives, offering a unique form of storytelling that is both personal and political.

How did you first come to incorporate embroidery into your artworks? What drew you to this medium?

Embroidery became a part of my practice somewhat serendipitously. I was initially drawn to its tactile and intimate quality—it’s also medium that carries a sense of tradition, labour, and care. Growing up, I’d see embroidery done at home, often in functional or decorative forms. When I began exploring themes of identity and heritage in my work, embroidery felt like a natural extension of those stories. It offered a way to physically stitch together fragments of memory and culture, creating a conversation between the handmade and the conceptual.

What does decolonisation mean to you personally, and how do you feel your artworks play with it?

For me, decolonisation is both an external and internal process. It’s about dismantling the inherited structures and narratives of colonial rule, but it’s also deeply personal—unlearning the ways in which I’ve internalised those narratives. As a first-generation migrant, I’ve wrestled with the ways colonial histories have shaped how I see myself and how others perceive me. My artworks engage with decolonisation by questioning and subverting visual languages that were altered or erased during colonisation. For example, in reimagining Indian miniature painting—a tradition disrupted and hybridised under British colonial rule—I’m responding to its narrative potential. I want my work to destabilise binary representations of identity and culture, encouraging viewers to see the nuances and tensions that exist beyond the surface.

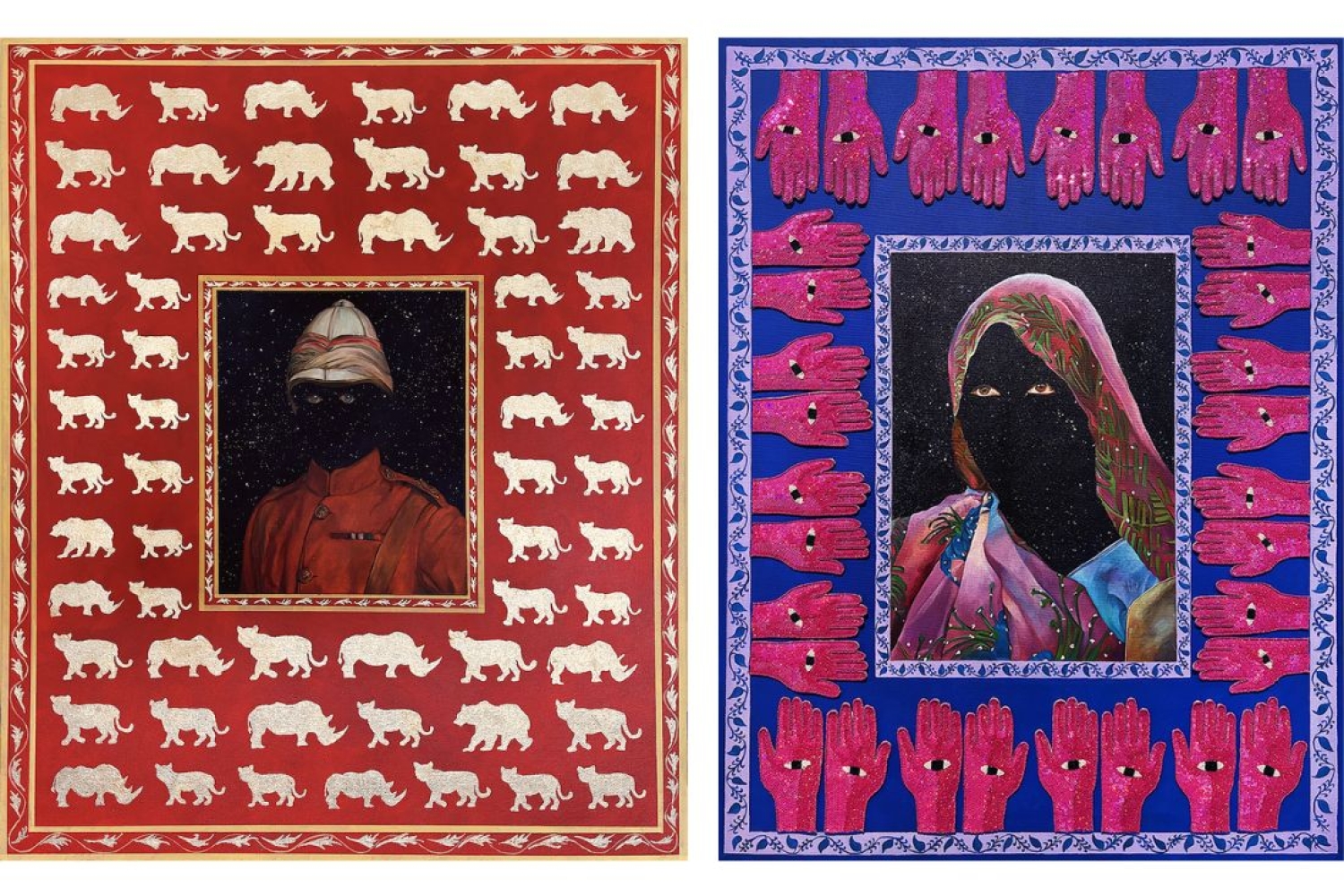

A Fly in the Milk I (left) | A Well Staring at the Sky (right)

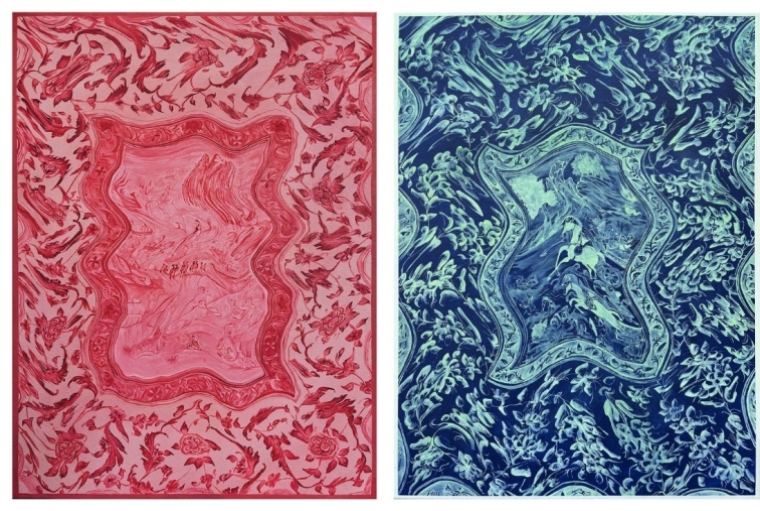

Can you tell me about your latest series, A Knot in the Thread? How does it reflect the effects of British colonisation on your personal identity?

A Knot in the Thread is a series that examines how the legacy of British colonisation continues to shape identity across generations. In this series, I was exploring the hybrid visual language created during British rule in India. I juxtaposed traditional patterns and motifs with fractured, distorted elements to reflect the fragmented sense of self that comes from growing up in a diaspora. There’s an inherent duality in the work—beauty and rupture, harmony and dissonance—which mirrors my own experience of navigating identity as someone tied to multiple histories.

A Knot in the Thread II (left) | A Knot in the Thread I (right)

I noticed a striking interplay of bright and muted colours in your works. How do you choose your colour palette?

Colour is incredibly important in my work, and I use it to evoke emotion and tension. For each series, I spend a lot of time researching the cultural and historical significance of colour within the context I’m addressing. The balance between the two is intentional—it’s about creating a visual rhythm that mirrors the complexity of the narratives I’m unpacking.

In your work, you’ve often explored a sense of dissonance between your Australian and Indian cultural identities. Do you think creating art from this place of tension offers a sense of resolution or catharsis, or is it more about embracing and exploring that ambiguity?

It’s definitely more about embracing and exploring the ambiguity than seeking resolution. I think the idea of resolution can be a bit reductive when it comes to identity—it implies that the tension can be 'solved,' when in reality, it’s an ongoing and evolving process.

Creating from that place of tension allows me to sit with the discomfort and complexity of my experience. There’s something profoundly generative about navigating those in-between spaces—they’re fertile ground for questioning and reimagining. While there are moments of catharsis in the process, they’re fleeting. The work is more about offering a space to reflect on the nuances of identity, rather than arriving at a definitive answer.

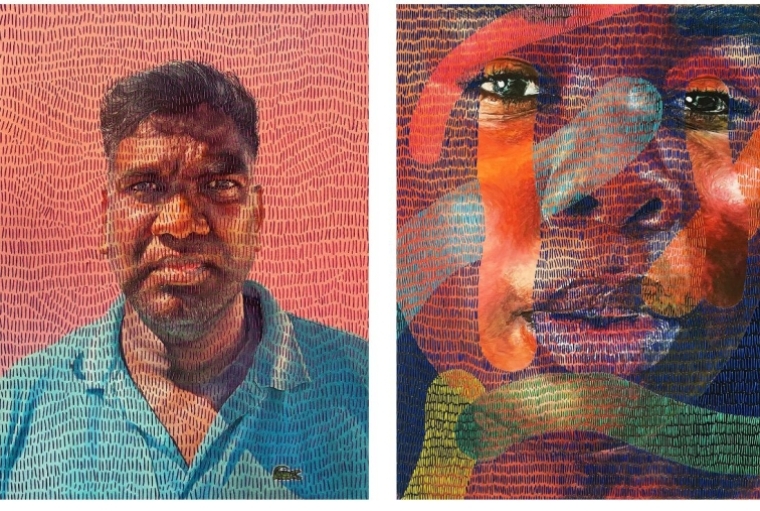

The Story of Us (Portrait of Philip) (left) | Portrait of Lillian Ahenkan (right)

What inspired you to depict asylum seekers in your work? What message or emotion did you hope to convey through that series?

The experiences of asylum seekers resonate deeply with me because they intersect with broader themes of displacement, belonging, and power—ideas that are central to my practice. While my own migration story is vastly different, the shared thread is that of navigating systems and spaces that often view you as 'other.'

Through that series, I wanted to challenge the dehumanising narratives that often surround asylum seekers in political and media discourse. I depicted them not as faceless statistics, but as individuals with rich histories and profound resilience. The works aim to create a sense of empathy and connection, encouraging viewers to see beyond the reductive labels and consider the humanity and dignity of those seeking refuge.

The Story of Us (Portrait of Evans)

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 13.01.2024