Anyone who has travelled to the hills of North India has definitely indulged in Bhuira jams. The simplicity of the jam-makers reflects in these no fuss, no preservatives, absolutely delicious bottles of artisanal jams. I have relished every flavour of Bhuira jams. Each flavour is hand-made, using open pans in small batches to capture the true flavour and texture of the fruit.

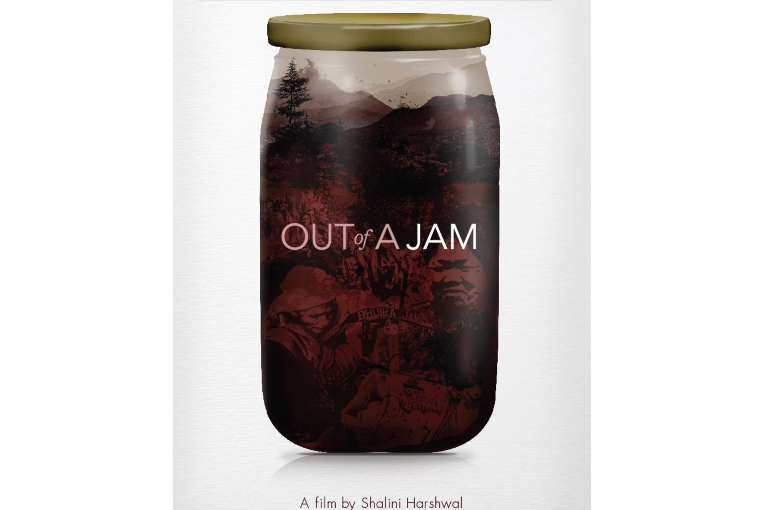

Ad-filmmaker, screenwriter, and award winning independent documentarian Shalini Harshwal, explored and learnt more about the all-female Bhuira jam community led by another very enterprising woman. In the process, Shalini realised that a lot can come out of a jam. ‘The film is about the success story of a group of Himachali rural women, bound together by courage and jams. They work towards shaping their common future by standing up for themselves and defying their patriarchal society,’ she tells me. I connected with Shalini to know more about the documentary, which was also recently released on MUBI India.

What kind of stories do you gravitate towards and what kind of stories do you want to tell?

Life itself is the best story to tell. What fascinates me the most is when humans rise above their situations and become greater than their challenges. Their true character is revealed in these very moments, when they are not defined or limited by their circumstances but rather what’s within them. I am naturally drawn towards this kind of heroism and simplicity. I hope to tell such genuine stories of human connection, endurance, and joy. However, whatever I do, I think women are always going to be at the forefront of it.

Shalini Harshwal

Out of a Jam is your first mid-feature length documentary – what inspired you to tell the Bhuira story?

When I first heard of Bhuira jams, it was an accident of fate. I was just curious about how a group of rural women made such amazing jams and wanted to know their story. So I reached out and Linnet invited me to visit them. The journey to Bhuira wasn't easy. After a point, the road ended and there was a kaccha rasta leading from the last small town of Rajgarh to Bhuira. It was pitch dark, with no street lights, no phone network, and just a long winding wobbly mountain road ahead. This place felt like literally it was in the middle of nowhere. How they managed a factory from here was unimaginable to me. It just didn't seem practical. The following morning, I saw all the women come to the factory after a long hike from their homes with a big, sweet and shy smile on their faces. There was so much innocence in their eyes. At the factory, they have a culture of doing everything on their own, including loading and unloading of trucks and there was no hierarchy amongst them. It was a very powerful visual.

When I spent some time with them, I learned their stories. I learned how happy they were to earn their own living and contribute to their families. To be taken seriously by people in their community. How fond they were of dressing up to go to the bank at Rajgarh every month, and be recognised as ‘Bhuira Women’. Now I knew why the factory was there. I realised it wasn't so much about the jams as it was about the women making it. I wanted to tap into that feeling and express it in the film. The inspiration to say their story resonated even more strongly.

Can you tell us a little about the documentary?

The film follows the journey of three primary characters. Linnet Mushran, the pioneer and visionary who started this factory and is in the process of making Bhuira women more self-reliant. Ramkali,a.k.a ‘Auntyji,’ the leader of the pack, the fierce maternal figure, the diplomat, and the full-time entertainer, who had a very tragic past, but brings everyone together and makes sure every woman in distress in the area gets some job at the factory. Sunita, a resilient single mother of three and a part-time employee, who in times of adversity fed on love and songs. She gets promoted to a permanent position at the factory. The story is about female leadership and shows the ripple effect when women become economically independent in the community at large. They display soft power by looking after the well-being of others, from getting their children educated to catering to the needs of the elders. Ultimately they take ownership of their own lives. The evening chai (tea) and the laughter they share; the sisterhood they form. They are the ultimate feminists.

It all began with curiosity regarding the delicious jam, but as you delved further, there were various layers you touched upon – what was the process like and what all did you discover about this little Bhuira community?

I wanted the women to get to know me and be comfortable around the crew before I started interviewing them. Initially, we would hang around in the factory, filming the process of making jams. It helped us not just to break the ice, but also in making them comfortable around the camera. That was very important to me. We would hang out with them during breaks and talk to them. Being an all-women crew helped us immensely. After a point, a bond was formed and they trusted us enough to open up to us about casteism, misogyny, their struggles, their children, their aspirations, and everything in between. That is how I could dig deeper and form the layers of the story. In fact, they shed all their inhibitions and sang and danced in front of the camera as well. Bhuira as a community is like most other mountain villages where people are very simple and hardworking. They have a culture of women doing a lot of hard labour and have very tough lives. Bhuira belongs to the most underdeveloped region in Himachal. They have a lot of issues regarding transport, electricity, and health care. Also, another phenomenon common there is that a lot of girls from poor families elope and get married to avoid wedding expenditure. I was pretty impressed by that!

Can you tell us about the founder of Bhuira jams, Linnet and her journey?

Linnet’s a passionate gardener, whose love for gardening actually reflects in her life. She blossoms wherever she’s planted. She makes a mark - she’s sharing the stage. She is a huge source of inspiration to me. Her life forever changed my perception of femininity and leadership. She takes her individuality and vision wherever she goes. From moving to India, starting a school in Bihar’s Gomia village, then a dairy in Thane, and finally a jam factory in Bhuira. Who would've thought? It takes a lot of gumption to do what she does. I just love her.

What were some of the challenges you faced and how has the documentary been received?

Being an independent film, it had its own set of challenges right from the start. Be it funding, post-production, and even promoting the film. Since I funded it myself, I had to do everything bit by bit, and mostly on my own. Gradually everything came together, but for that to happen I had to quit my day job and work on it exclusively for almost a year. I was supported by my wonderful family and a set of very close friends who contributed to this film and helped me get it over the line.

The film started doing rounds of film festivals in 2015 and I traveled with it to two of them in the U.S.A, where it won the best international documentary award at the LA Femme Film Festival. I received a lot of love and appreciation there. People had a lot of questions about the caste system and about Ramkali. She clearly is a superstar everywhere. It was also the first audience interaction I had, so it was special. To find a platform for a documentary like this in India was a bit of a struggle since we don't have great documentary exposure in our country. Now with MUBI, it became possible for a filmmaker like me to showcase my work. Since its release on MUBI India, I've had people reaching out to me with messages about how the film made them feel and how moved they were. I’ve received great reviews. From not having a platform to receiving so much appreciation, it is overwhelming and exciting. It definitely struck a chord with the audience and it encourages me to do more such work.

It’s always so heartening to see when businesses, big or small empower the underprivileged. What did you take away from the final documentary?

When individuals or organisations decide to set up their business in a rural area, they help not just build their brand but also the community, the effects of which are long-lasting. It might take the time to create the right infrastructure and some difficulty to get the workers trained, but the reward is exceptional. I say this because when the effect of a business is so deep in your society, the kind of loyalty and commitment one receives is unmatched. There is a heightened sense of responsibility and ownership that people have. It’s a source of pride and identity for them. Which is exactly the case with Bhuira women. It's an ideal sustainable business model. I remember a similar model of a jam factory being replicated right in front of Bhuira’s second unit. They wanted to replicate the recipes so they even tried poaching the girls from Bhuira Jams. None of them budged! Can you believe it? Eventually, their business did not take off as they had expected. After all, it is not just about setting up the business but also about people who run it.

Lastly what are you working on next? Also, after we all cross this challenging hurdle – what will be the new normal for you?

Right now I am working on a feature film script which I am very excited to direct. I was hoping for it to go on floors this year but, by the looks of it, it might have to wait. What seems more plausible is a new documentary which I had initially planned for next year, because that’s where I can be hands-on and shoot it myself. Limited crew and virtual collaborations are going to be the new normal for filmmakers, something a documentary filmmaker is already used to. Due to this, we might see a surge in documentaries. I hope that the new normal for our society would be where we are more mindful of the common good and help each other get our life back on track.

Text Shruti Kapur Malhotra