"Cinema serves as an audiovisual means of communication. It has the capability of conversing with you, making you hear and see at the same time. It occupies not only your two senses, but through those it suggests all the environments of the other senses as well it makes the world you are being presented with almost complete."

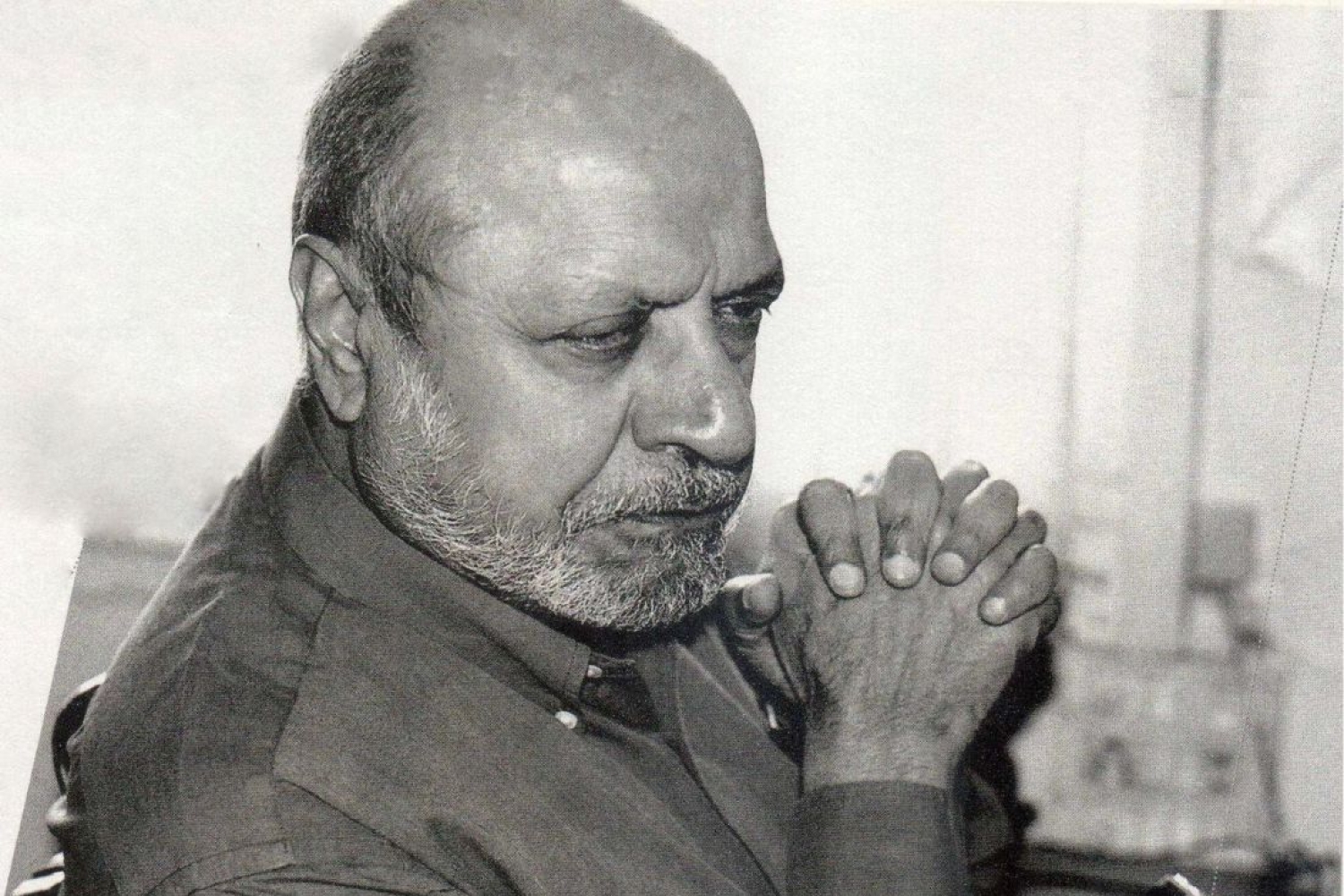

Serenity is the first word that comes to my mind when I describe Shyam Benegal. He seems particularly tranquil and as though he could deal with any situation, however catastrophic with a shrug and a smile. We talked for a while: he listened to my questions attentively, often pondering for a minute before answering.

Benegal's career has spanned over four decades and trying to identify the zenith of his life and work is a futile task. He began by working in the ad world, as at the time there were no film institutes to speak of and he felt that working with an established filmmaker would limit his exposure to the medium. As he says: "it would have been like several blind men with an elephant. I would have only known the parts that I could feel"

Benegal made over 900 commercials and in the process learnt everything there was to know about filmmaking, whether it was writing scripts, cinematography, editing, sound recording, and mixing. He got a taste of everything. "I learnt the grammar and the vocabulary of filmmaking through making ad commercials," he says.

Benegal's first full-length feature, Ankur (1973), which featured Shabhana Azmi in her debut, brought the issues of feudalism and patriarchal systems in rural India to the forefront of the cinemagoers consciousness. His film Nishant (1975) focussed on the sexual exploitation of women and for many years most of Benegal's movies concentrated on social issues. Benegal has also produced a 53-episode television series on Jawaharlal Nehru's Discovery of indio called Bharat Ki Khoj (1998) and a documentary called the Making of the Mahatma, which depicts Gandhi's early years in South Africa.

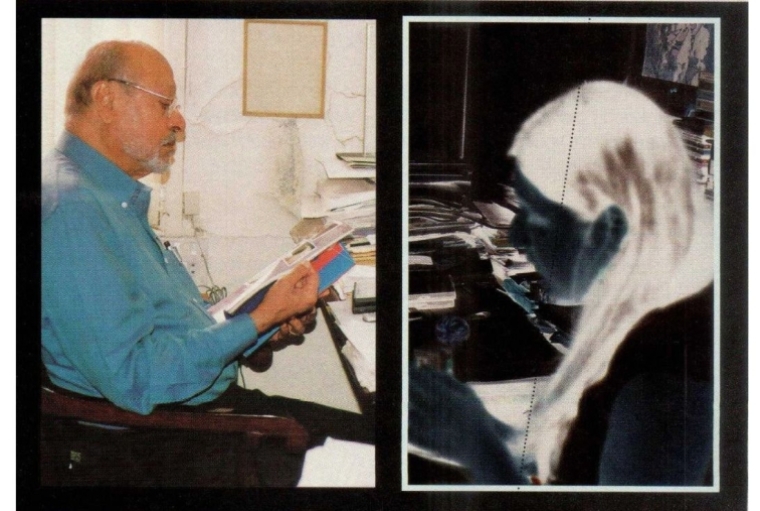

The 71 year old director visibly enjoys getting down to explaining the nitty gritty of his work, but reveals that he is not very attached to any of his filims. Once the film is complete, he says, the umbilical cord is cut and he lets go. "I become objective as then my film has to develop a connection with the audience."

Benegal is however attached to the experiences and processes of making films. He says: 'In many ways films are like your children. They grow up and go away. They are yours but you should not be afraid of them being criticized and run immediately for their protection as they can look after themselves."

So says the man who has won great acclaim for his work and has more than sixty films to his credit. With a Padma Bhushan, Padma Shrit, national and numerous international awards on his mantle, Benegal is humble about the recognition bestowed upon him. He says: "I feel very happy because it is something that people within your profession consider as good, and when it comes to recognition by the state, you appreciate that as well because it means that they are recognizing you as a useful member of the Indian society."

When I ask what style he would characterise his work by, Benegal delivers an answer that is different than what one so often hears. Rather than associating himself with a particular genre, Benegal belleves that a filmmaker is characterised by the new expressions he or she reveals. "A filmmaker only emerges when he or she has found his or her voice. That very simply means that you have found a way that is unique to yourself, a way to express yourself, and that becomes your characteristic. And that in cinema becomes a style", he says

Benegal admits that his style, or voice, has remained relatively unchanged through the decades. He says:" while the world keeps changing, there are certain things that are universal and remain unchanged. Certain abiding values that you live with and believe in do not change. What changes are the strategies, tactics and the social and political environment."

To my surprise, Benegal does not have much of a reaction to the recent trend of extreme violence and hyper-sexualised content of mainstream Indian cinema. He very collectedly states that violence and sex have and will always be the selling ingredients of cinema. According to him it has been present forever. The only worry should be that it should not be crass, crude, vulgar or callous as then the audience gets desensitised to violence and sex. That is the real danger, states Benegal.

He speaks with enthusiasm and passion about his forthcoming film called Subhash Chandro BOSE-The Forgotten Hero. Benegal admits that this is one of hidream projects as Bose has served as a hero to him since his childhood. According to Benegal Subhash Chandra Bose is the only warrior politician India has ever had. "I had wanted to make this film for a very long time but did not have the funds. Fortunately Mr. Subroto Roy also wanted to mate a film on Netaji and I got to meet him and things fell in place", he excitedly states.

The film took three years to make, as it required copious amounts of research and a large cast of supporting actors and extras. Benegal has tried to stay as true as possible to the events of Base's life, and so the film follows the freedom fighter's footsteps through the streets of India, Ladakh, Uzbekistan, Germany Burma and South East Asia.

After leaving Benegal's office in Mumbai, I am left, with a torrent of thoughts and feelings about this legendary filmmaker and his work, He is cerebral but down to earth, seasoned but passioriate. He has a natural authority but made me feel completely at ease. Benegal's cinema is different in terms of both form and content and uses filim in a number of ways as a tool of poltical expression, as a means of personal introspection, as a merciless mirror amed at society and as a medium through which to explore new forms of story telling.

Words Kopal Naithani

Photography Vijay Kumar Shaw

Date 25.12.2024