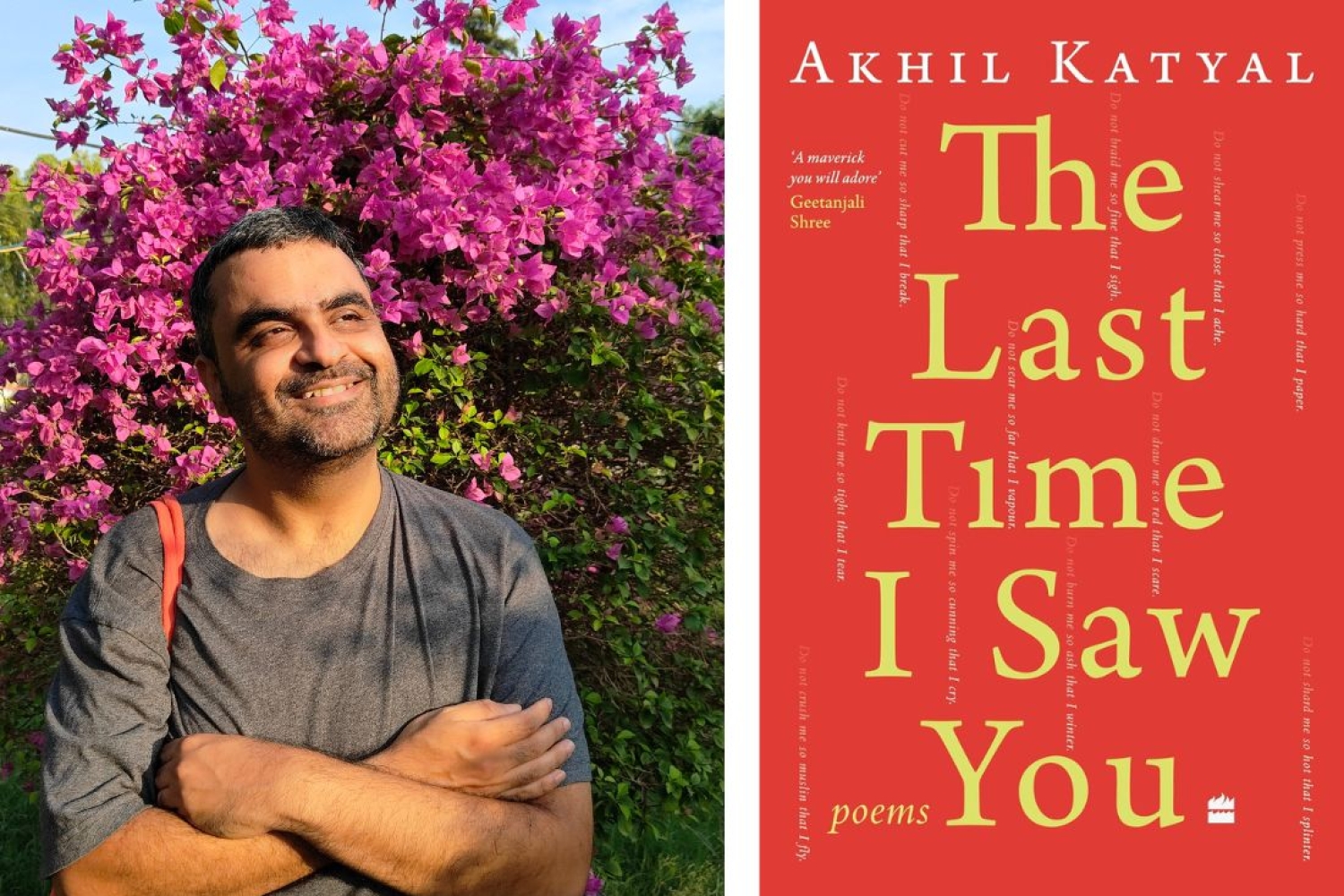

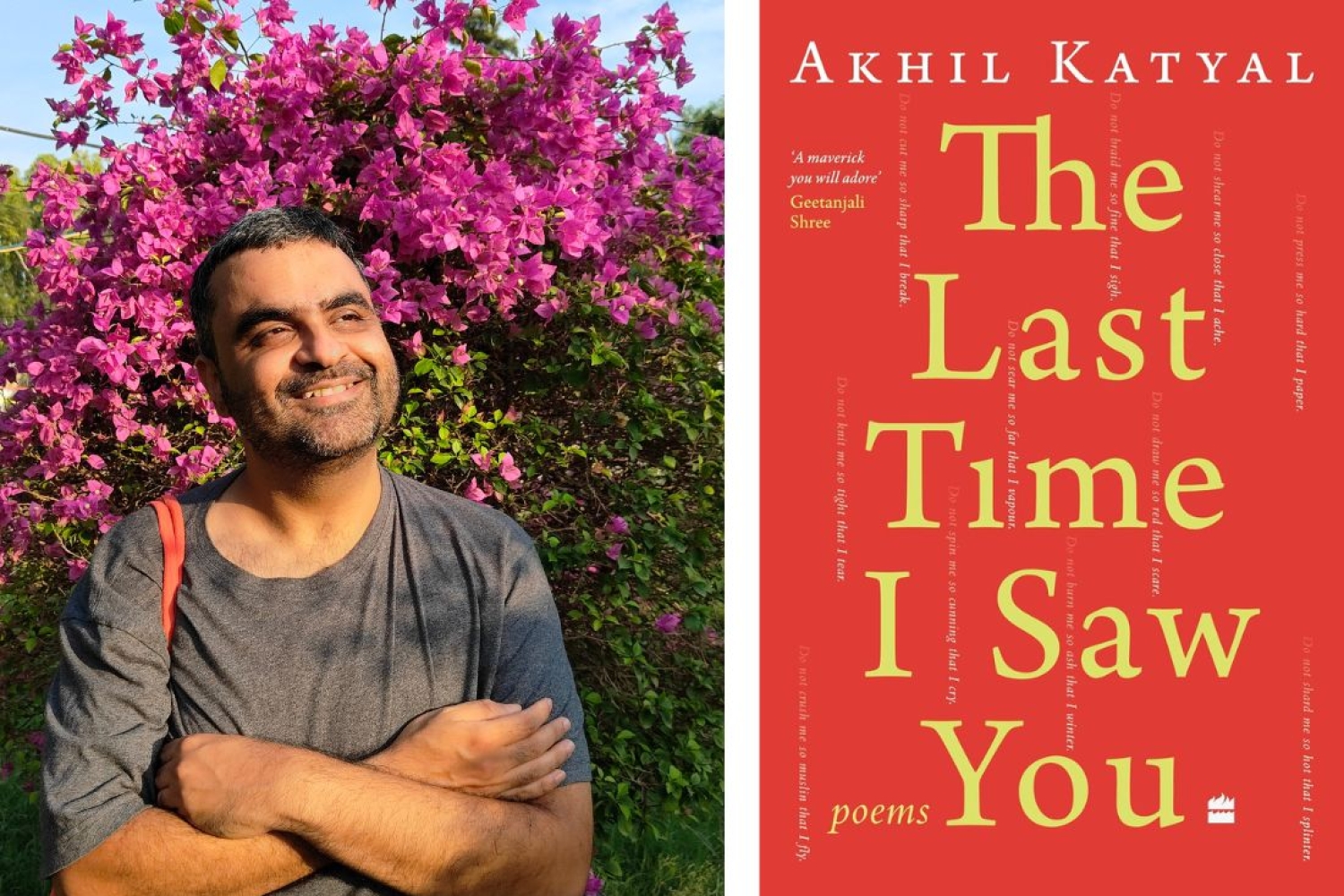

Akhil Katyal has long explored cultural and personal emotions through his poetry, resonating with many readers along the way. Countless people have been captivated by his succinct word choice and the simple stories of daily life that he can convey in sometimes mere three lines. A friend of mine, his former student, describes him as someone who understands poetry in a unique way and excels at processing its craftsmanship. Having woven the essence of Delhi into his work, Katyal has now relocated to Mumbai, where he may offer us a fresh perspective on the maximum city. For now, he continues to guide us through the streets of Delhi, highlighting the well-known landmarks but also revealing the city’s unknown corners, in his new collection, The Last Time I Saw You.

In grappling with personal loss, he finds solace in the city’s animals, trees, rain, people and sites. We discuss the structure of his new book, his inspirations, and of course, the city that developed his poetry.

How did you decide on the various forms for the book, including everything from one-line poems and haikus to longer pieces?

The book is written in the aftermath of a difficult event of personal loss. Over time, such an event is processed and understood in many, many ways. Sometimes its sharp sting is felt, sometimes it casts a long shadow over your life. The different forms, I suppose, are attentive to the different shapes through which loss comes into our lives. The haiku will attend to the pinch of such an experience within its syllabic restraints. The long poem with its capacity to hold and manage excess, will be able to speak about the long duree of loss and the way it would sediment slowly into our lives. As a poet, I value both the economy of expression and the ability to deftly elaborate the contours of experiences, whether of places, people, animals, or objects. Different forms allow me to do this.

The poems evoke a deep nostalgia for figures like Begum Akhtar, Intizar Hussain, and Bismillah Khan. How does this sense of nostalgia influence your style of poetry, which is very contemporary?

In one sense, I am not interested in nostalgia. These figures are living, breathing entities for me. They are ways of looking at our world. These ways might be under deep sense of threat today, but they won’t simply scamper away in fear. Each of these figures allows us a unique vocabulary for who we are as people, as Indians, as folks navigating a deeply anti-Muslim present, as people struggling to keep some form of bonhomie between different communities alive. Begum Akhtar’s singing gives us an exquisite vocabulary for things we prize and may lose, whether these are particular people or entire worlds. Intizar Hussain knows cities and irreversible cultural and political changes like the back of his hand. Ustad Bismillah Khan knew a thing or two about the frictions and possibilities of coexistence of religious communities which we may do well to never forget. Theirs’ are threatened imaginations but also resilient ones. Their art and their persona give me words when I run out of them.

How has your relationship with Delhi changed over time in your poetry, especially in light of your experiences with grief and longing?

No city is ever the same. In one sense, I think what we fundamentally know as urban is always necessarily shifting and entropic. In terms of built environment, in terms of people and their mobilities, in terms of enabling or disenfranchising public policy, in terms of longstanding, sharpening aggression against communities, whether Muslims or Dalits, in terms of things constantly being lost and added. These are all the ways in which a city constantly metamorphoses. We bring to this mass of change our own changeable selves, fragile and formidable both. As a young university student, I was starry eyed and made all sort of goof ups. As a young lover, I was ready to make the biggest promises and place them in people and places. As a first-time teacher, I was exploring my city for the first time on my own terms, trying to be both daring and rigorous inside the classroom, and full of surrender and friendship, outside it. As an older man, in his late thirties, when I left the city, I left both broken and remade, attentive to the city’s silences and euphoria, to its givens and its possibles. The Last Time I Saw You is not simply an elegy for a person lost, but also for a city which allowed me both to savour this loss, and finally to severe myself from it.

Rain appears frequently in your poetry. What does it symbolize for you?

Thank you for making me aware of this. Now, that I think back on it, it is true. I often go to the image of rain. The image is so plentiful. It allows you the sense of being soaked, the sense of absolute inundation, the sense of something being finally washed away after months and months of dryness and deracination, the promise of a life after, on somehow newer terms. The rain in the northern Gangetic plains is also very unique. As one of my favourite poets used to say, and I paraphrase, the rains do not come to the northern Indian plains at their appointed hour, they make you wait, they make you long for it. Which is why there are such robust and heartbreakingly prosperous artistic forms in northern Indian literature, in painting and in poetry and in music, that devote themselves to the rains. Perhaps I take leaf from that book. But especially today, rain is not just an image, it is a stark thing. In these time of erratic climate changes precipitated by unprece- dented global warming, where cities and countries face flash floods, storms, and when no season looks like the last time it came around, in its intensities and durations, this promise of a little rain as a place of love is both utterly fragile and perhaps a quiet plea for the sort of rain, which is not always, already marked by the machine of human activity big enough to alter global climate cycles. Maybe this kind of ‘rain’, this soft, beautiful kind that occurs in the book, not the destructive one we are familiar with our news cycles, is where the strong strain of nostalgia actually works.

You have stood on the shoulder literary giants like Naomi Shihab Nye, Eunice D’Souza, John Keats, and Krishna Sobti. What aspects of their work resonate with you?

Intertextuality is how my work often comes into being. Not from some mysterious inner place, not from some hazily understood fount of expression inside us. No. It is quite the other away. I read, like so many of us do, in order to understand myself and be able to find language for it. When I read Shihab Nye, I understand that a disarming lucidity of language can capture the most complex of human experiences. In De Souza, I find the epigrammatic, the sharp, the sardonic as very playful and very accommodative registers of writing and being. In Keats I find a combination of restraint and lushness both. In Sobti, I see what hoops our languages, Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, English, can jump through. Each time I cite these authors I tip my hat to them but also I hope to cut some of my poems from a cloth like theirs.

What do you hope readers take away from The Last Time I Saw You?

As I said, The Last Time I Saw You was seeded by an event of personal loss. In its final turn, the book attempts to shore up a dignified, even plentiful vocabulary for loss from the larger chaos that visits us when we lose someone. Each of us has lost someone, to circumstance, to illness, to a whim, to unrequitedness, to a place from where they do not return. What do you do in the face of such a loss? How do you inhabit it? The book begins to outline the contours of such a habitation. I hope the readers will find in its world something that they will recognize from their own. Perhaps it will make them inhabit their own difficult times if not with fortitude, perhaps, with dignity.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 15.10.2024