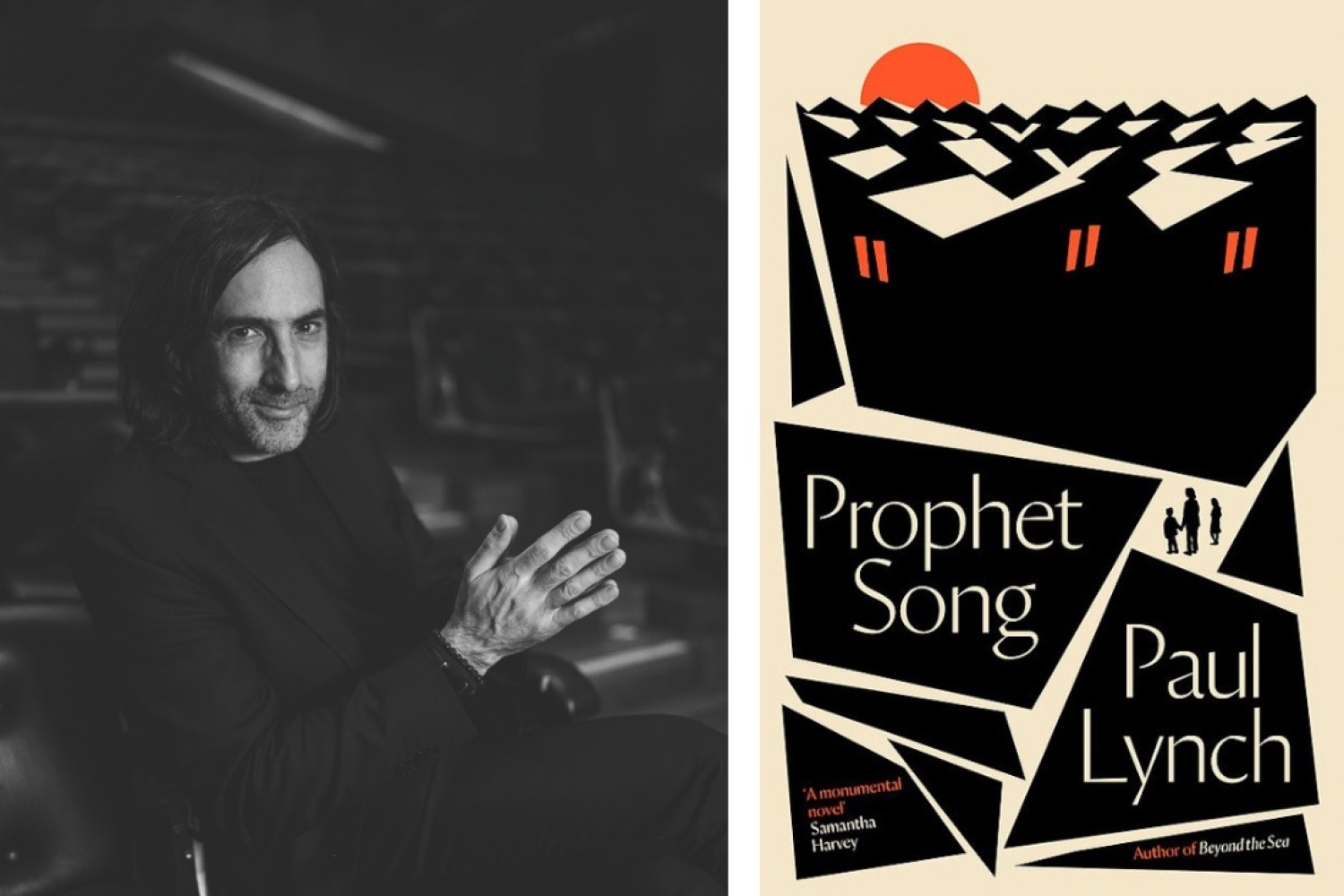

There is the tale of the miracle appearing when everything is at its darkest, only to be affirmed by Paul Lynch and his incredible experience. Laying under the scalpel for cancer and battling long Covid, rebuilding his life and finding himself again after an ended marriage, fathering a toddler and suspending the book he was in the midst of writing to start another…The Booker Prize, no doubt, came like a spark of affirmation for the Irish author last year, reinforcing his belief in the mysterious ways of life. Prophet Song, his winning title, is also a tale as strange as the Loch Ness monster of the British countryside, where the story is set. The monster, in this case, is the social anxiety triggered by an absolutist regime reflective of the present times; a society on the verge of collapse and the modern predicament of civilisation that looms over the main characters. Eilish is a microbiologist and mother of four whose life is ruined when her husband, a teacher advocating better conditions for the trade, disappears on account of state sedition in Ireland. The four children are painted from the author’s recollection of the poignant picture of the Syrian child, Alan Kurdi, washed up on the shore – the empathy raised four-fold. As a father of two children, Paul’s own experience of parenthood appears in the endearing details of the protagonist’s life as the everyday normal in the midst of the big mess that is the world.

The author’s inspirations are rooted in the world’s socio-political unrest, the Syrian conflict and the indifference of the West to the refugee crisis. He began at home, weaving a paradox around the deeply personal rather than the political, staying away from heavy histories or dry fact. The fascist frenzy does not dissolve the essence of human existence and emotion which is at the centre of life, however dystopian. His craft is a portal of uncertainty, his process disciplined with writing two hundred words in a day, with a window for unknown visitations woven into his total trust in intuition. This translates as the quality of timelessness that is evident in his work, despite the urgency of events. A lot floats between natural metaphors. The skies and fields he grew up in are alive and active in his prose. Glimpses of poetic mysticism in the form of darkening gardens and daily enchantments evoke the aesthetic of cottage-core and sometimes quickly transform as tragic cottage-gore. Paul is a believer, not in the conclusive novel but in the act of asking important questions and feeling things intensely. His long, breathless prose stands testimony.

Nothing fully stops, everything is paced between commas, defying every rule in the book, taking the reader by hand and running through burning streets, so that there is no way out of the page, the moment and the present – thus creating immersive, experiential old-media art out of empathy. It’s a call to attention, a cry for compassion. What is the agency of an individual in addressing a shared problem? Paul wanted to test if fiction, as a form, could possibly change the soulless discourse that the news and social media unthinkingly play out, pandering in most cases, to power, instead of the people.

Buzzed with the energy at the Jaipur Literature Festival earlier this year, he deconstructed his writing self with utter simplicity and strength. Edited excerpts from the interview.

What made you pick up the pen at first?

Well, I think that writing is a conversation. If you’ve been reading great literature all your life, sometimes you get to a point where you want to communicate back with the writers you’ve been reading. And sometimes the need to write, is really an impulse of authenticity; you feel like you have something to say or something to communicate through language. That decision to become a writer is fundamentally an act of authenticity. It has got nothing to do with wanting to be a writer — with wanting to be somebody in the world. All of that is irrelevant.

Growing up, you worked at a bookshop and did not have the easiest childhood. (Some notes seem to find their way to the book: as the mother raises her kids, the author pays an ode to his own). You never graduated from college; do you think we place too much emphasis on academics?

You don’t need a degree to be a writer but education is really important and I never advocate that people should drop out of their degrees. What’s important is that you find your own journey; you find your own route through life and my particular route was that I just wanted to work with language. I wanted to work with words all day long. And so, I had an opportunity, when I was very young, to work for a newspaper — a national newspaper in Ireland and I started working as a sub editor and I realised that this is what I wanted to do. Even though I had no idea then that I wanted to be a writer, I just knew I wanted to be with words. I am lecturing in a university now, which is a grand irony and very amusing

to me. My advice to anyone who wants to be a writer is, ask the question – Do you like words? Do you like language?

Tell me how the story of Prophet Song was inspired. What are your thoughts on the relationship between the personal, the political and the poetic?

It was that sense in December 2018 when I sat down to write that the world had changed considerably but that we hadn’t noticed it change. I re-read Hermann Hesse’s Steppenwolf and there was a passage that I remembered reading in my early 20s that talked about the great destruction that was coming to Europe, the next war. He could sense what was going on by watching what he talked about – the anti-Semitism and the xenophobia on the streets, the complete fracturing of politics. When I read that in the late 90s, I thought that it must be extraordinary to be alive in such a time but it seemed like an alien period whereas re-reading the book in 2018 was to recognise the same world. So that’s the power of great literature – you’re never the same reader twice and also, it is a mirror. I understood that the times had really changed and because things change by degree, changes are very slow.

There is an interesting structure to your prose. It is fluid. It does not follow the rules of your journalistic or literary training. Tell me how you came to it and how important it is for writers to experiment with form.

When you sit down to write a novel, form is something that reveals itself to you and part of what shapes it is the meaning that you want to convey. So, there’s a sense of reality in this book. There’s a sense of the real that I wanted to impart to the reader. I wanted the reader to feel like they’re inside the moment. The form took shape with long sentences, the feeling of the present tense and just that sense of how the moment moves fluidly, how the feeling of events can be felt within the text. Eilish finds herself caught up in something that has an enormous momentum and within that momentum, the reader feels themselves locked into the text as Eilish is locked into the feeling of events. So, there’s no room to breathe. I think that every decision you make as a fiction writer must associate back to the meaning of the book.

A lot has been said about specificity and detail in writing. How do you think ambiguity is important to the writing process?

Life is fundamentally strange and we don’t know who we are in the world most of the time. Ambiguity is actually a default state. We don’t know what’s coming, we don’t know the future. We act decisively all the time as human beings. We believe if I do this, this will be the outcome. This is the great human tragedy of all. This is what defines so much of Greek tragedy – that we act with certainty but we reap the crop of the unforeseen. And I think that writing should try and convey these things. I think that writing should articulate the fact that we’re in the labyrinth and that we don’t know where we are.

This is an all exclusive excerpt from our Bookazine. To read the entire article, grab your copy here.

Words Soumya Mukerji

Date 11.11.2024