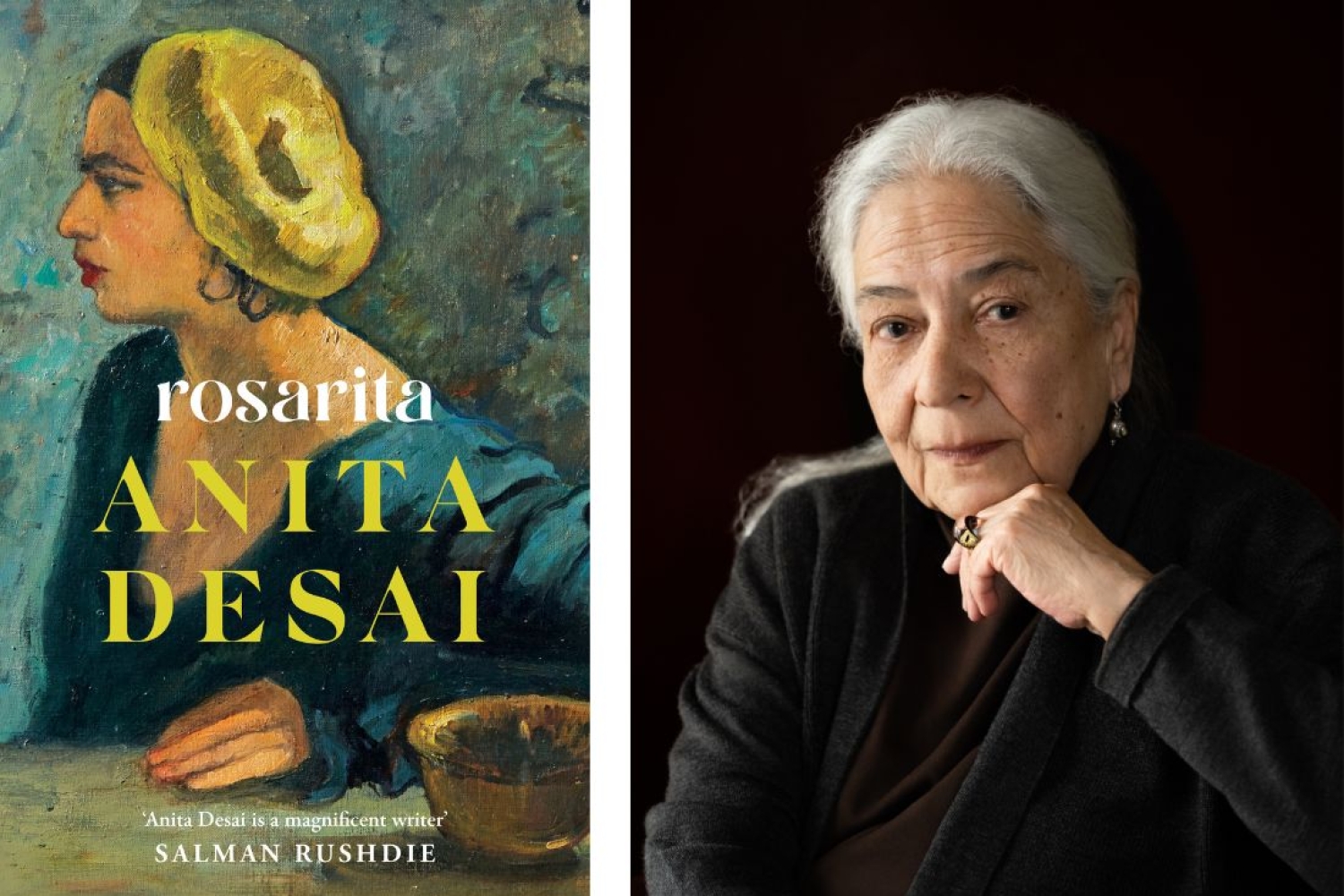

When I first read Anita Desai’s 1989 Booker-shortlisted novel In Custody as part of my literature course in Delhi, I didn’t fully grasp its depth. However, what stayed with me was the way her rich prose brought the charm of Delhi to life. Over time, this has been one of Desai’s greatest strengths—imbuing different cities with a living presence in her work. Desai has transported readers to various locales, from Calcutta and Bombay to Massachusetts. Now, she takes us to San Miguel, Mexico, where we meet Bonita, a woman who encounters an elderly stranger claiming to be a friend of her deceased mother.

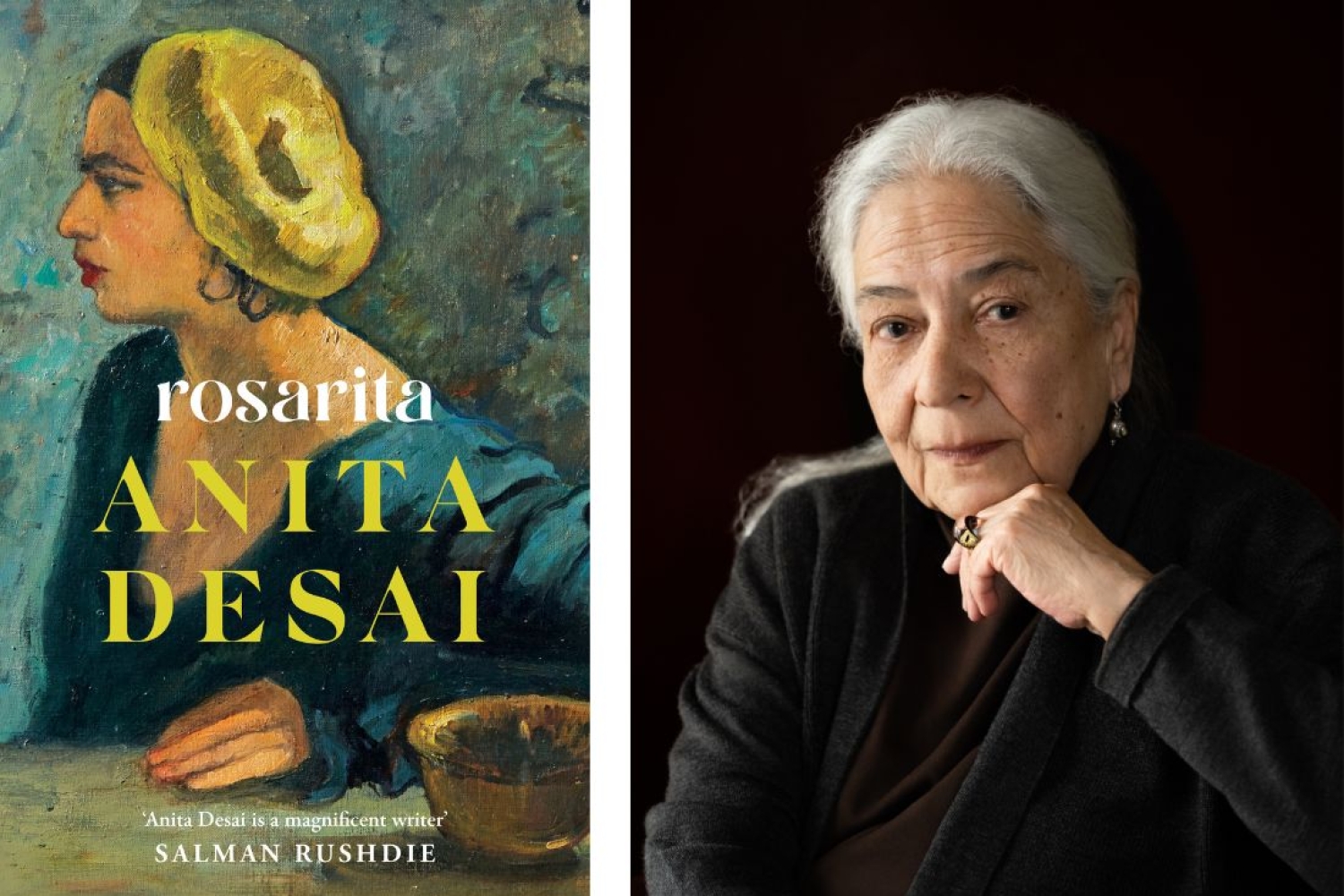

At the age of 87, Desai returned to the literary scene with her first novel in a decade. Rosarita explores the gulf between a mother and daughter in around hundred pages. The protagonist, Bonita, meets a stranger, who hurls memories of Bonita’s mother’s life in Mexico, which Bonita initially dismisses, ‘Your mother never lived in San Miguel, never even visited Mexico. You know that – the absurdity of such a suggestion!’ However, her little knowledge of her mother’s life throws her into a torrent of questions and grief, leading to her unwilling engagement with the stranger. She thinks of possibilities of her mother’s connection to Mexico: 'Were those trains she saw on the screen with their unspeakable cargoes, the ones that could have carried the Muslims of India to Pakistan and the Hindus of Pakistan to India, also the ones that carried her family across some savage new border from which few arrived alive?’ Drawing on the history of Partition and the migration of refugees to Mexico, Desai weaves a labyrinth of questions, grief, loneliness, and the immigrant experience—all explored through an unexpected encounter.

We ask Desai some questions on her break, the novel’s form, grief and her writing process.

How has your perspective as a writer evolved over the years, especially after such a long break, and how has this influenced the writing of Rosarita?

The years have brought rich experiences of course and perspectives change. With dwindling time, energy and stamina, I find myself increasingly attracted to the short form ie., the novella for my last two books. I wish I could write poetry but have failed to do so.

Why did you choose to use the second person pronoun for the protagonist in this novel?

I found the second person voice allowed me to draw readers into unfamiliar and remote locations more quickly and immerse them in them more fully. I avoided a third person perspective which would have intervened and created distance. Only the mother's section was written with a third person's perspective and voice because it was imagined and remoteness and distance were appropriate there.

Grief makes us look for the lost ones in many delusional ways, why does that happen? Why Bonita became obsessed with the supposedly false story of an old woman that she herself considered a trickster?

Grief over a space once occupied, then emptied, I think compels the grieving one to fill it with memory and imagination. The narrator, Bonita, had not even known she missed her mother till the Trickster appears and forces her to remember her thereby also forcing her to acknowledge how little she had known her which makes her feel the need to somehow recreate her.

What role does research play in your writing process, especially when your stories are set in diverse and culturally rich locations like Mexico in Rosarita?

The need for research varies. An earlier book called 'The Zigzag Way', for instance, required much research into the history of mining in Mexico by foreigners and the disruption caused to it by the Revolution. Rosarita was based entirely on the working of the imagination and required very little — just a few notes in the afterword to show the historical background for it. Addressing that more fully would have made it a very different book.

Can you describe your typical writing process, from initial idea to finished manuscript?

Initially, I write down random notes composed of passing impressions, experiences, ruminations. Then, as they fill a notebook, I see they are not so random after all but have links and start stringing them together. Eventually that develops into a narrative that becomes the book. It is perhaps like finding scattered pieces of a jigsaw puzzle and trying to fit them into a coherent pattern. It is the practice of turning what had seemed chaos into a composition, which is also a practice of turning the unconscious into the conscious. I write the first draft by hand on paper. Also, the drafts that follow two or even three. Then, type out the one I decide to send my editor at the publishing house. The editor will get back with comments and suggestions. These go through delicate negotiations between us till we arrive at the final version to be sent to the press.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 23.12.2024