Image: Shahbaz Khan

Image: Shahbaz Khan

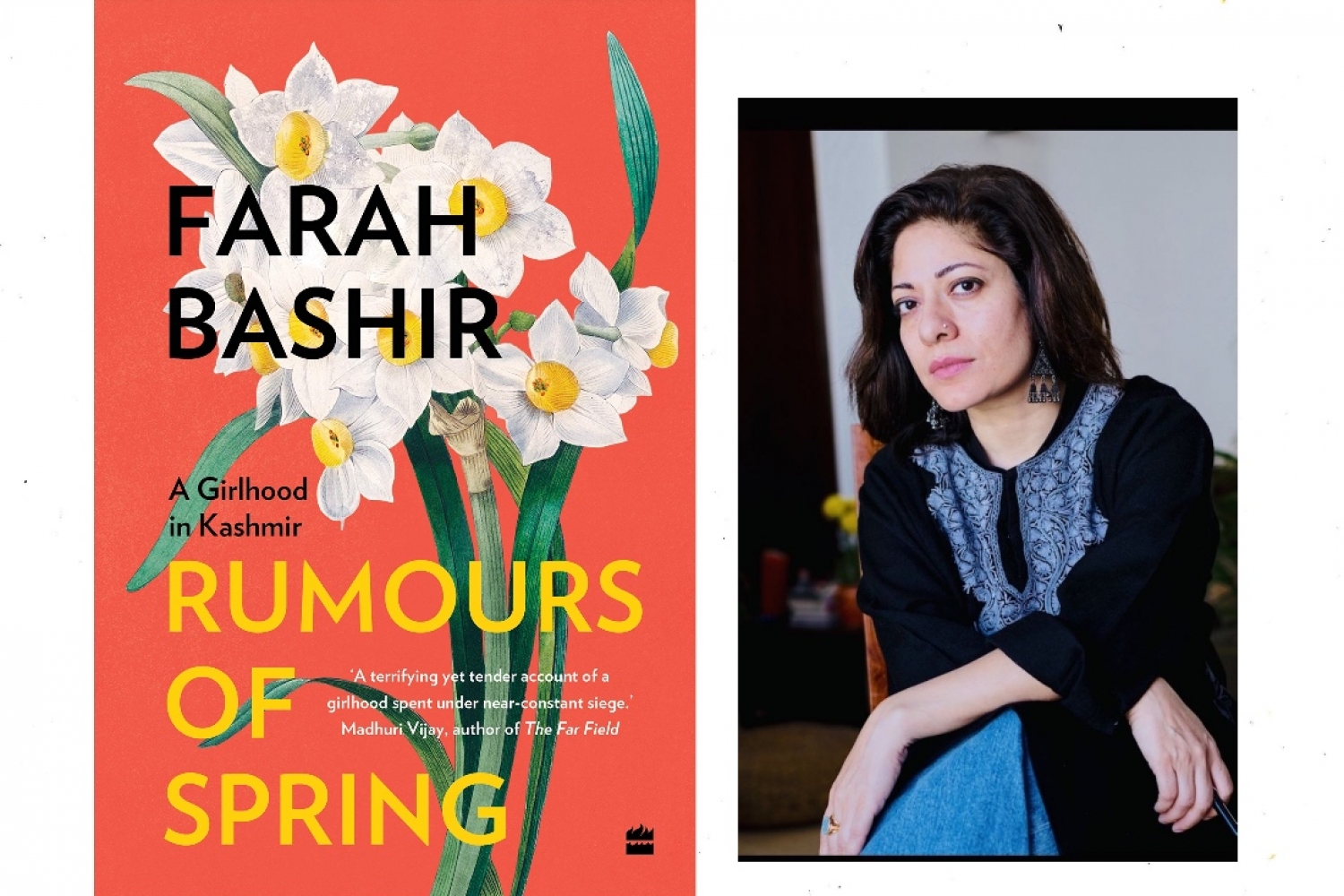

“It is not uncommon for writers to debut with memoirs if they belong to conflict zones or geographies that see a sudden political shift and their lives change overnight,” quoth Farah Bashir, explaining her decision to debut with her autobiography. This statement made it powerfully obvious to me the lack and necessity of voices like Farah Bashir’s, in the scarcely known space, that is, the past and present of Kashmir.

If one looks back at literary history, the female voice emerged rather late as compared to the male voice and phallocentric language had pervaded the discourse about the history of this world and our understanding of it. When it comes to instances of war and conflict, the masculine perspective is given even more significance. However, history is never objective and female subjectivities are essential in its recollection and reiteration, ‘Anne Frank’s Diary’ is one such novel that touches beautifully upon a girl growing up under the Nazi regime, the voice of a million others. ‘Rumours of Spring: A Girlhood in Kashmir’, is thus a vitally important book as it stands alone at the intersection of a feminist bildungsroman and an account of Kashmir in the 1990s. As Farah Bashir takes us through her coming of age against the backdrop of conflict-ridden Kashmir, the growing violence, insurgency and militarisation outside begin to break through and enter domestic spaces. Life is consumed by fear and uncertainty. Farah’s description of anxiety during the most prosaic tasks every day is simple yet haunting. Eventually, the socio-cultural and political intermingle in her narrative in a way that is both enlightening and agonising.

My conversation with her:

From being a photojournalist to now a communications consultant, how were you led towards writing?

I used to work with the Global Pictures Desk, Reuters in Singapore. From having edited news from Iraq, Palestine, I didn’t see Kashmir take the kind of space that it warranted internationally even after being recognised as the disputed territory under the extant ‘UN security council resolution 1947’ formed in 1948. Seen as some low-key South Asian conflict between twoneighbouring countries, some colleagues used to joke that the world isn’t interested ‘because you don’t have oil’, which is probably what it is. Though, I used that period to read extensively on Kashmir, for the first time, to understand the nuances of politics, aspirations and betrayals than just trusting the lived experience and memories simply from growing up there during the 1990s.

While working, I remember sending a picture of a rather brooding girl, sitting in a shikara, to the Times Square (as Reuters used to have direct access to it back then). It invited a comment from one of the editors that it looked too grim. It didn’t look pretty and I didn’t have an answer for him at that moment. In hindsight, it felt like that was the moment in which I wanted to represent ourselves and draw world’s attention to what Kashmiris, as a people, had been and were enduring. The Kashmir conflict, as we know it, hasalways been reduced to binaries: if they don’t want India, they must want Pakistan, if they are not patriots, they are traitors, it’s either tourism or terrorism. Simplistic as it is made out to be, rarely anyone talks of the political aspirations of a people who want to decide their own future. A year after I left Reuters in 2008, is when I began to write, but had to keep multiple jobs over the years to pay the bills.

Which authors and books were your early formative influences?

‘Little Women’ by Louisa May Alcott, ‘Memed’, ‘My Hawk’ by Yasar Kemal, ‘Portrait of a Turkish Family’ by Irfan Orga, ‘Beloved’ by Toni Morrison, ‘The Late Bourgeois World’ by Nadine Gordimer, ‘Agha Shahid Ali’ and (the more recent one) ‘Sharon and My Mother-in-Law’ by Suad Amiry.

What inspired your debut book, ‘Rumours of Spring: A Girlhood in Kashmir’?

Before the August 5th, 2019 unilateral abrogation of the article 370, there had been three main historic events in the contemporary history of Kashmir. In 1846, The Treaty of Amritsar was signed where Kashmiris were sold by the British along with their land to Dogras; the 1931 uprising against the Dogra rule, during which unarmed protestors were fired upon and killed and the armed rebellion in 1990 against New Delhi. We have no literary account of our social history from those periods and it became urgent to record that. Militarisation doesn’t only maim and kill but it alters societies and traditions. Subtle changes occur and they start replacing the old way of life without us even noticing. Bunkers within the city started becoming our ‘landmarks’. An odd detail that neither me nor my late grandmother got used to.

As our land and our lives continue to transform fundamentally by a pitiless conflict, as the arc of the moral universe doesn’t seem to bend towards justice, remembering and processing the 1990s, the crucial years of my adolescence became necessary. As a teenage girl, growing up in a conflict-stricken territory happened to be a dual struggle: to make sense of the militarisation of domestic spaces and to learn new social etiquette — informed by war — to navigate life. Besides, the voice of a young woman on the literary landscape, was yet to be heard from Kashmir.

Since the book is so deeply personal, what was your writing process like as you were tapping into your experiences while penning the book?

Courage to face what had seemingly passed. In total, I took about ten years to write it. In the first seven years, I used to leave it and return to it. From 2017, I spent five hours every single day for eighteen months writing it, no matter how difficult the memory was. There was a chapter ‘A wedding, A funeral’ in which I write about the gruesome killing of my first cousin, my inability to cry at his funeral, which I had to confront in the last draft finally. The pain was too raw and there was no way to escape it.

Also, I had arranged the chapters thematically earlier, but as I spent time with the subsequent drafts, I realised I hadn’t written much after my grandmother’s death. To make it easier for the reader, I used that as an anchor to hold the narrative together.

How much did our increasingly intolerant present socio-political scenario affect what you’ve included and not included in the book?

I wrote to honour the memory and identity of a young girl and I had to be true to that. Making changes as per the socio-political climate wouldn’t have made the book. It currently is. The manuscript went through the lens of legal department at HarperCollins and I had to provide citations to about fourteen instances in the book. My editor, Sohini Basak, was extremely brave and supportive and she encouraged that we look at ways to add references than change anything. Thankfully, we didn’t have to delete a single sentence.

What was the toughest part of making this debut and how has it affected you as a person?

The courage to keep returning to the memories, to delve deeper into the trauma; personal as well as collective. To feel the weight of world’s apathy yet again. It has also made me realise how one text is not enough to contain the enor- mity of events that have happened in the nineties in Kashmir and their impact on women.

What kind of a relationship do you share with Kashmir now?

I am going to quote a line from a poem by Mahmoud Darwish on this one, “I have learned and dismantled all the words in order to draw from them a single word: Home.”

Lastly, how have you been coping with the pandemic and what’s next?

I am aware of the enormous privilege when I say that I have used the pandemic to watch films, read and edit the final drafts. It has given me space to work uninterrupted. But sometimes it felt like curfew in the 1990s, but the only difference was that one was safer at home. Home was the opposite of safe back then. I am now working on a group portrait of women spanning across a decade.

This interview is an all exclusive from our Bookazine. To read more grab your copy here.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 05-11-2021