Photography by Hemal Shroff

Photography by Hemal Shroff

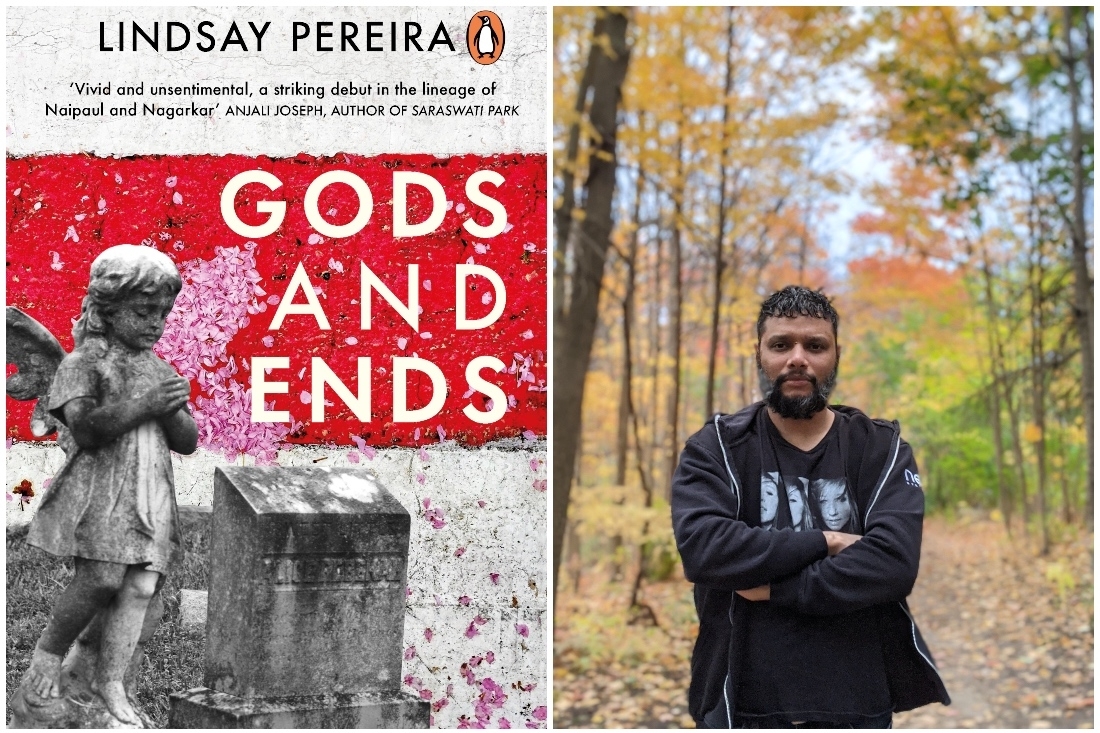

Bombay has been portrayed by artists in myriad ways. Some romanticise the city, some demonise it. There is no dearth of narrative on the city, its beauty and its struggles, which might make one think that all the diverse facets of the city have been portrayed or talked about in our literary history. Lindsay Pereira’s debut book, Gods and Ends, poignantly overturns this assumption. The part of the city in spotlight is the suburb of Orlem, on the canvas of which, Lindsay paints the portrait of a Roman Catholic community. In a chawl named Obrigado Mansion, we meet the various characters, whose stories signify the brutal reality that is scarcely known to those outside. Women in this chawl are consumed by violence and repression, while others are stuck within tragic circumstances, which are beyond their control.

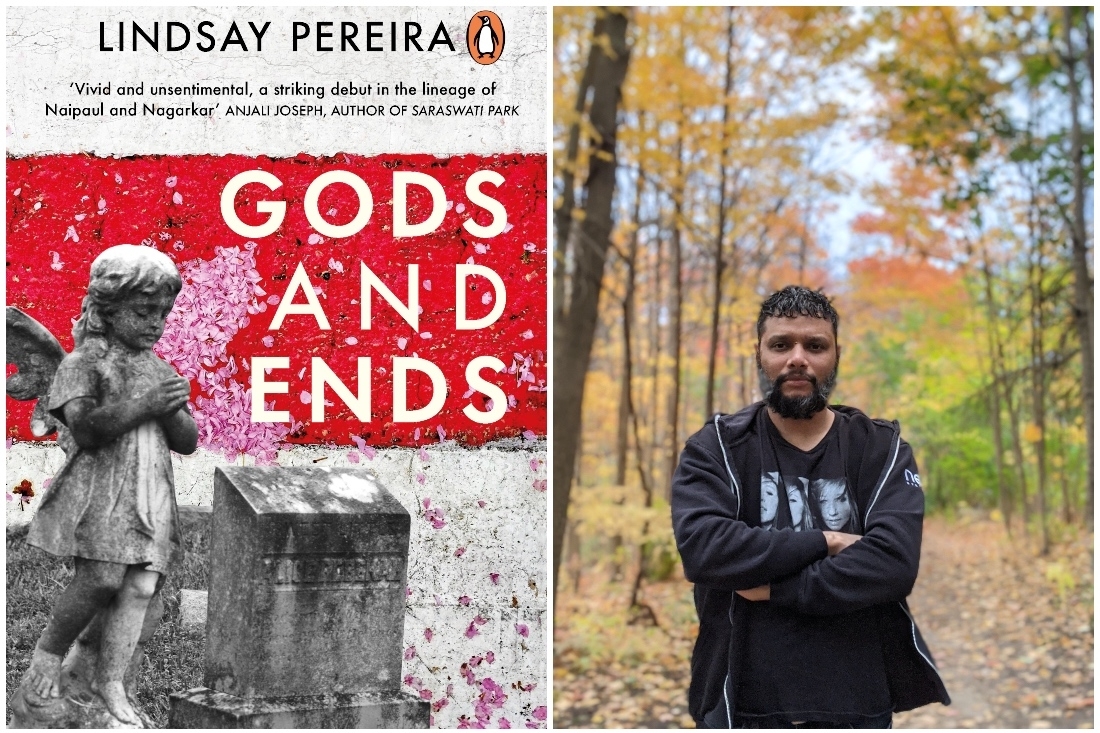

The author’s roots in Orlem, lend this book an indescribable authenticity. The tragedy of this book and its characters is real, and the narrative manages to create necessary space for the lives and stories of people, who are generally erased from our imagination of the limitless city of Bombay. We connected with Lindsay to know more about the book.

From being a journalist, how were you led towards the world of fiction?

It happened by accident, because I realized I had a story to tell and needed a format that could do justice to it. I believe one world informed the other, because my emphasis on everything I did as a journalist was the human side of a story. I brought that to bear upon these characters and their fictional lives in a way that felt almost organic.

Could you tell us about the writers and books that have informed or influenced your work?

Everything we choose to read affects us at a subliminal level, even if we try and identify some writers or books that have a more tangible, profound impact. I spent decades studying literature, so it sometimes feels as if the classics have always been a part of my life. It took me a long time to be able to say with some confidence that I had a style of my own that wasn’t derivative. I suppose it is more accurate to acknowledge the framework of certain books that shaped my narrative, from Altaf Tyrewala’s work to how Rohinton Mistry used the short story to shine a light on a particular community.

What inspired your debut book, Gods and Ends?

I wanted to tell stories about people who do not traditionally find themselves and their realities reflected in the fiction of our time. We are trained to have specific beliefs and ideas about how other people live, and I wanted to counter those established narratives. I wanted to hold a mirror up to people and places that were not being looked at as much as I thought they should.

The book narrates and oscillates between the stories of one character at a time. Could you give us an insight into how you conceived and built the characters?

Every character represents an idea, or sentiment. I wanted to use them in ways that allowed me to comment on the inherent hypocrisy that lies at the heart of all religious belief, for instance, or the misogyny that is endemic, irrespective of place or faith. I tried to differentiate them with the use of voice and tone, switching from first to third person, or employing linguistic rules that would allow readers to keep track of individual story arcs.

Your debut book is located in a topography that is very familiar to you. What was your creative process like behind writing the book?

It was an act of remembering and reimagining, because it has been years since I lived in the places described. I wanted to capture an ambience more than a location, and deliberately focused on dialogue as much as possible to introduce nuances that I hoped would work.

What kind of challenges did you face with the debut?

One writes with the assumption that one has something to say. I had no idea if what I was doing had any merit. Then there is the anxiety of influence that may be more pronounced when one is within poetry but casts an undeniable shadow on fiction as well. I had no way of knowing if the voice I believed was my own would be recognised and accepted as such, so finding a publisher was a form of validation. That was probably the biggest challenge.

What do you hope the reader takes away from your work?

Among the responses I have received so far, two stand out. One reader said they had no idea a community like this existed in India. Another said she felt as if she was being seen for the first time. I think they both embody what I wanted this book to accomplish.

Today, what does Bombay mean to you?

I believe much of what made Bombay special died in the 1990s. Nostalgia is fickle, so I hesitate to romanticize what may have always been a ruthless city. I continue to love and respect it though, because no other Indian metropolis offers that potent mix of ambition and possibility. One feels alive in Bombay, irrespective of the hour. It can be cruel, of course, but it always thrums with the potential for magic as well.

How have you been coping with the pandemic and what will be the new normal for you post it?

The pandemic has been revelatory in all kinds of ways. It taught me how much I hate socializing, and how I appreciate my own company. I don’t miss anyone as much as I assumed I would, and have used this time to read, listen to music, and slow down. I intend sticking to these habits.

Lastly, what’s next?

I have been asked to consider writing for new formats, which I may do depending upon my schedule. Covid-19 has taught me that making plans is an exercise in futility, so I don’t make them anymore.

Text Nidhi Verma

Date 07-04-2021