The International Booker-winner Michael Hofmann proudly wears the hat of being a translator, poet and a German with his strong critique of literature and a passion for both the Germany and its language. When I ask him about a word that brings spark in his life, he mentions ‘Logomancy,’ which he describes as the magic of playing with words. Having translated more than hundred titles from German to English and four volumes of poetry, he’s undeniably someone who does understands the divine magical forces of playing with words and language.

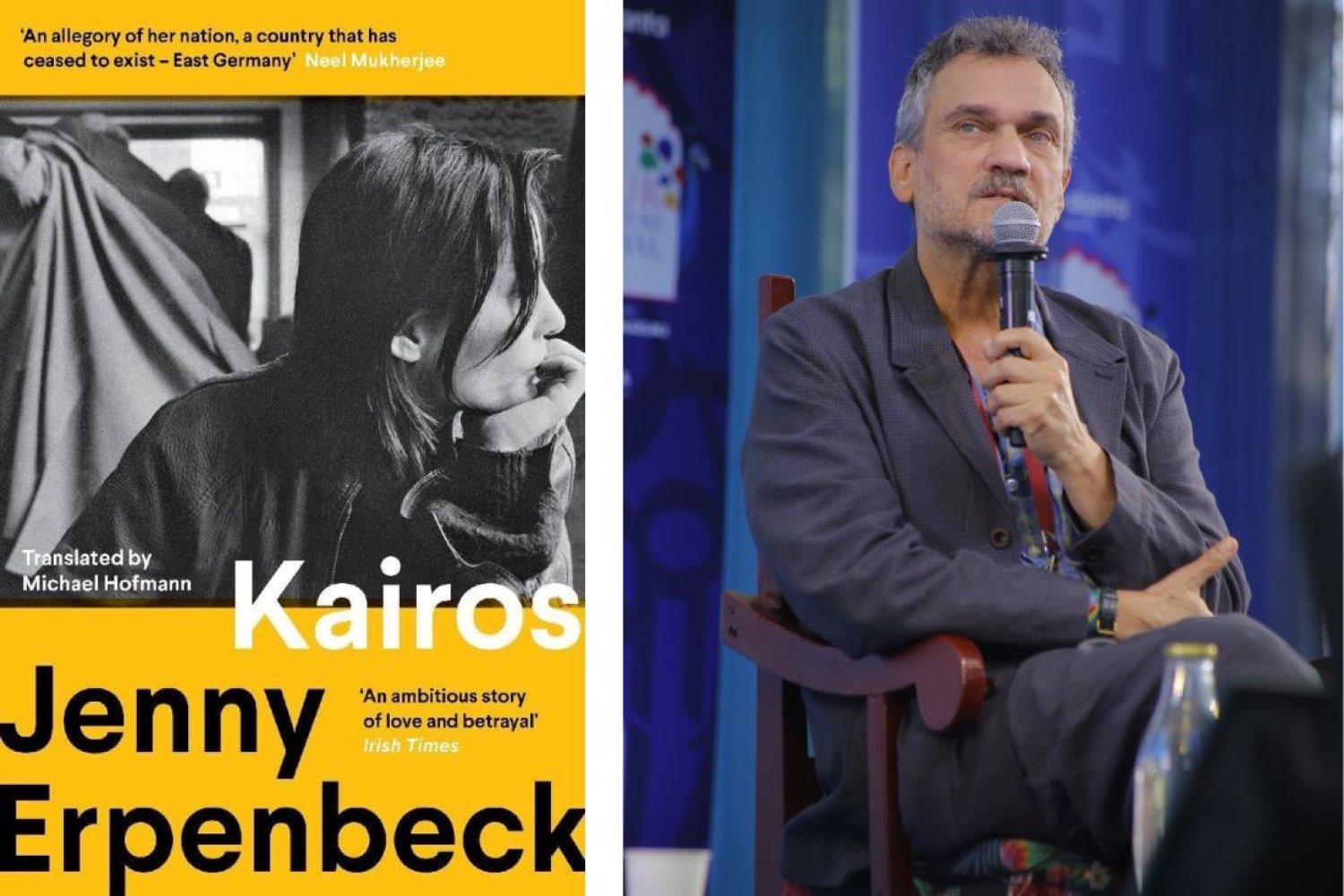

Having translated works by literary giants such as Franz Kafka, Joseph Roth, and Hans Fallada, Hofmann earned the International Booker Prize for his translation of Jenny Erpenbeck’s Kairos. A book that follows the devastating love affair of a 19-year-old student and a married man in his 50s, set against the backdrop of East Germany. Hofmann’s translation captured the novel’s luminous prose while preserving the nuances of East Germany, ensuring that the country’s cultural elements did not fade into the English language.

We caught up with him at the Jaipur Literature Festival last weekend to discuss his relationship with both German and English, how he navigates dual roles of poet and translator, and his approach to translating classic as well as contemporary writers.

I want to start by talking about your experience with the two languages, German and English. What is your relationship with both of them?

There is something rather hefty in me, which is sort of vehement. I quite often say things against English, I have a sense of an antagonistic relationship with English. Whereas, in the last five years I've been living mostly in Germany and I think I've really come to like and love German. To some extent, I am sorry that I was taken out of Germany and that my working language is English and will remain English.

I used to think that you need to have one language to play with and a language to work in. You can't write a poem with just one language.

What do you mean by there's a language you wake up in and a language you play with?

I think there's something very humdrum about English. I mean, everybody speaks it, everybody understands it. How can a language that everybody speaks and understands be beautiful? How can it be original? And especially in England, where not only the British speak it beautifully but other nationalities as well. I think I get a sense that other nationalities have a more beautiful and maybe a richer sense of English than the English do.

You've translated the classics from Kafka and Brecht to contemporary writers like Jenny Erpenbeck. What sort of evolution have you noticed in German writing in itself?

There are sort of two things. I think one is that a lot of the things I've done from the 20s-40s, which was a classic period in German writing. There were many good German writers. After these years, the social and historical things had all happened. People moved into the cities and had jobs. There's a limit to what you can talk about in your domestic, private life. The war has sort of gone away.

Then, there was the unification. And I remember when it happened, there were some instant books about it. They weren't very good. And I thought it would take the Germans at least 20 years to produce a really good book about unification and I think Kairos has done a great job.

Since you're also a poet and translator, so these are your two major forms. I was wondering if there is ever like an overlap of these two creative forms? Do you ever apply your translation brain onto a poem you're writing or vice versa?

Not really. I think there's a Nietzsche saying, ‘what doesn't kill me will make me stronger.’ And I've translated so many books that either poetry will be completely crushed by them, or else it'll come up through these books and it will have learnt something from producing many different millions of words.

Tell me about your translation process. Are you too much committed to text or you wish to add your own flavour and does it change from book to book?

It does. Now everything is on laptop. I don't know anyone who doesn't translate directly onto a computer. But I used to work longhand and then type on a typewriter. In a sense, I miss that process. In my own practice, I also do the translating right away so I have a draft and leave spaces for words I have to look up. As soon as I have an English draft I will then put away the German and just work with the English. And I think at that stage there's maybe freedom of pushing things around a little bit.

A translation is only in one language when it comes out and I may as well spend my time on that language and not expend it on the original.

I was conscious, almost in an artificial way, that this is an East German book and I wanted to signal East Germany. I wanted to signal no blue jeans, consumer society, youth, power, or entitlement. I wanted to show that there are products but there isn't a great array of choice. These things are all sort of subliminal.

What was the process of translating Kairos? Was the process unique and different from your other works?

I was conscious, almost in an artificial way, that this is an East German book and I wanted to signal East Germany. I wanted to signal no blue jeans, consumer society, youth, power, or entitlement. I wanted to show that there are products but there isn't a great array of choice. These things are all sort of subliminal.

I had an American editor and it was important to me that the book doesn’t come out sounding American at all because the Americans are the most privileged and entitled youth anywhere and the book must not have that sort of sound through me.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 04.02.2025