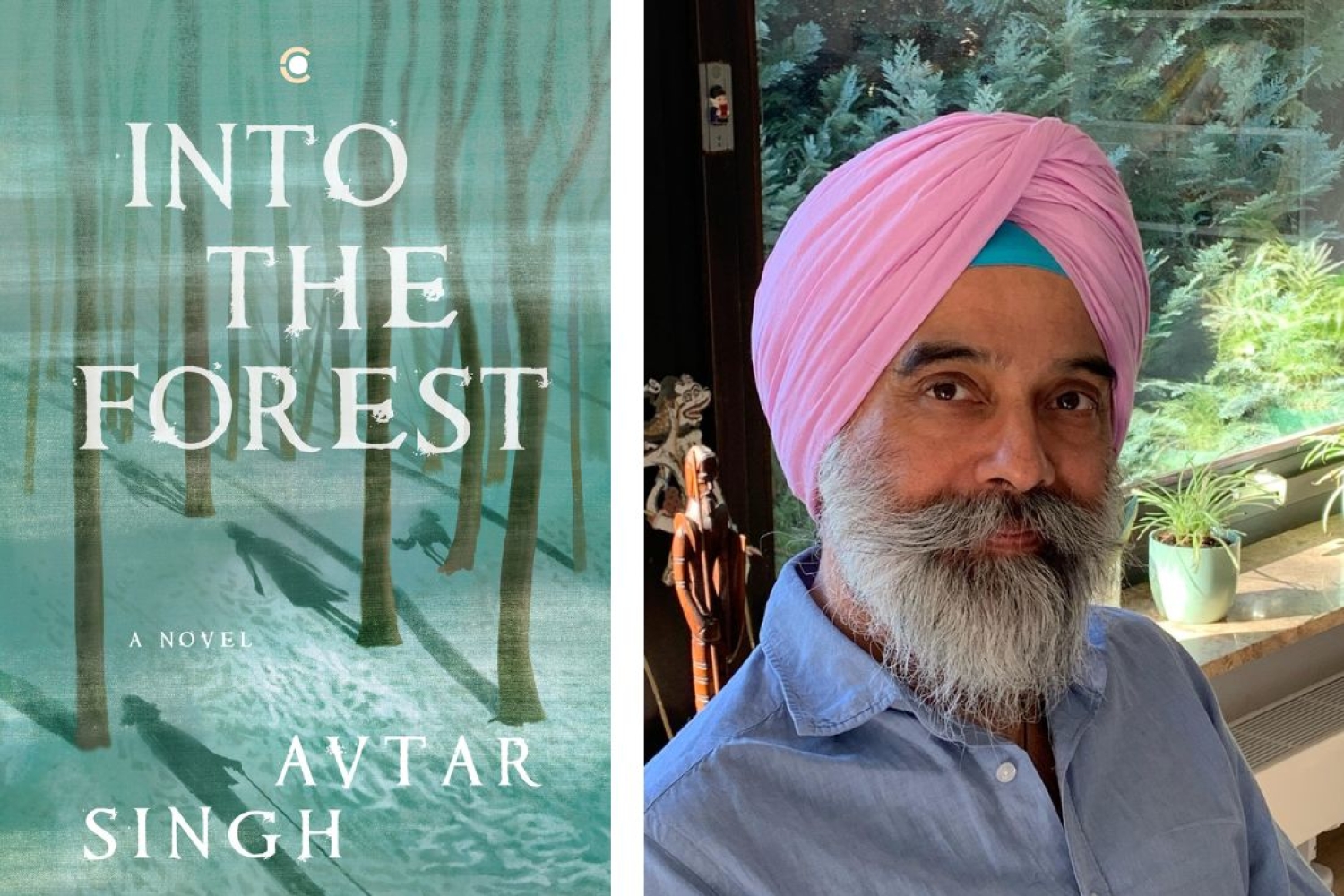

In Into the Forest, Avtar Singh intricately weaves his personal experiences with the narrative, setting his novel in a quaint German town by the forest—a fictional reflection of his own journey and struggles during the pandemic. Through a narrative rich in emerging friendships and unexpected disappearances, Singh masterfully explores themes of loneliness, isolation, and the quest for belonging. His novel not only sheds light on the struggles of displacement but also celebrates the enduring strength of human connection and acts of kindness amidst adversity.

In this interview, Singh discusses how his immersion in the forest, coupled with the diverse characters he encountered, shaped the novel's unique blend of storytelling. He explores the role of investigative reporting in his narrative, the nuances of migration and much more.

What inspired you to set the book in Germany, and how have your personal experiences in the country influenced the novel?

I arrived in Germany in August 2019. My son was settling in a new school; we were all getting used to a new place; and then COVID came. In that sense, Ahilya’s experience of a new place, a town by the forest in Germany, mirrors my own. Through that first lockdown and its uncertainties, walking in the forest with my dog was my refuge. Again, that connection with Ahilya! It helped me make sense of it all (if anybody can claim to have made sense of that mad time).

Writing about things is how I deal with them. This book grew very naturally out of the notes I kept, the people I met, the things I saw. Nabi is based upon many young Afghan men I met in my Migration/German language course. Physically, Liesl is based on a neighbor. Her calm demeanour comes from the same source. You could draw a line like that to every character in my book. But also, I write fiction. None of this actually happened; the things I saw, the people I met – when I put them to paper, they took on lives of their own, which followed their own logic.

I was dreaming of people and their deeds as I walked. Then I sat down to write about them. Into the Forest is the result.

Tell us about your research process for this novel.

I know these people intimately, because I invented them. My research for this book was confined to feeling them out, their worlds, as closely as possible. I didn’t have to look up any events, or historical notations, or read any books. I was living that period.

What motivated you to explore the story through the lens of investigative reporting?

The figure of the reporter that bears my name is a framing device. The first chapter of Into the Forest is retrospective; the events it mentions have already happened. Once the stage is set, he disappears, and only reappears at the end when the story arrives at its chronological end. In a sense, he is peripheral to the story. He sets it up, and then the reader is inserted into the story itself, as it happens. The reporter isn’t required anymore, because the events he is “investigating” are happening in front of your eyes.

Why a reporter? There are disappearances. Possibly a murder. I’ve written a book about a policeman. I felt I needed a different point of view.

What nuances of migration were you aiming to highlight through the characters' stories?

I’ve lived in India and the USA, in China and Germany. I’ve embraced migration. I’m not alone in this. The world is marked by migration, and much, if not most of it, isn’t even voluntary. In my migration course in Germany, refugees sat next to software engineers. Our own country sees internal displacement on a vast scale, whole communities pushed out because a dam must come up, a road must be built, a forest needs to be cut down.

Migration – and its demonisation – is one of the core narratives of our era. Unless you’re living in a walled village dreamt up by M Night Shyamalan, your life is touched by it.

Among other things, migrants carry the freight of their memories. Leaving isn’t the only thing that has weight. Arrival presses upon you. That negotiation with a new place; the ways in which the emigrant makes it her own: this is of enormous interest to me.

Forests have long been depicted as mystical places in literature. Why do you think this is, and how does your novel contribute to or alter that perception?

There are still communities around the world that live in forests. However, most of us don’t. The ways we think of a forest, name it, even conceive of it, betrays our early training. Look how Indians use “Junglee”. And yet, many of us are drawn to these spaces. Is it something atavistic, a need deep in us to be wild and free? Perhaps it is something as basic as a need to be tied, root and branch, to an older, more natural world. I don’t know. Angela Carter writes beautifully about wild spaces and our connections to them. Others, spout psycho-babble.

I love trees. I always have. I stop to look at their crowns, feel their bark with my fingers, sit in their shade. I wait for the birds and the small animals to forget I am there so they can go about their business again. I have lived a deeply urban life, and I’m comfortable with that. But forests speak to me. I don’t feel the weight of explanation, if that makes sense. The forest is a character in this book. It is that simple. The idea for the book wouldn’t have come up if I wasn’t walking with my dog in the woods. The book itself wouldn’t have come into existence if the people I dreamt up didn’t meet in that space.

Find a forest. Walk in it. Not a “brisk” walk. Turn off your phone and your smartwatch. Just wander. Slowly. As you would with an old dog, at his or her pace. You might dream as well.

Words Platform Desk

Date 22.08.2024