“I did my bachelors in Computer Science. I didn’t know what I wanted to study when I got into college either, so I emulated my successful siblings. But after I started to work at Google I knew that tech wasn’t what I wanted to do. Around the time, my family started to pressure me to have an arranged marriage as well. I didn’t know at the time that I was gay but some survival gene within me screamed against it. So I moved to the Gurgaon office of Google and once I was there started to trek through the Himalayas nearly every weekend. I felt gratefully small amongst those peaks and my problems felt insignificant. And it was there that I felt the need to write, not travelogues, but fiction,” shares Shastri Akella of his journey towards writing.

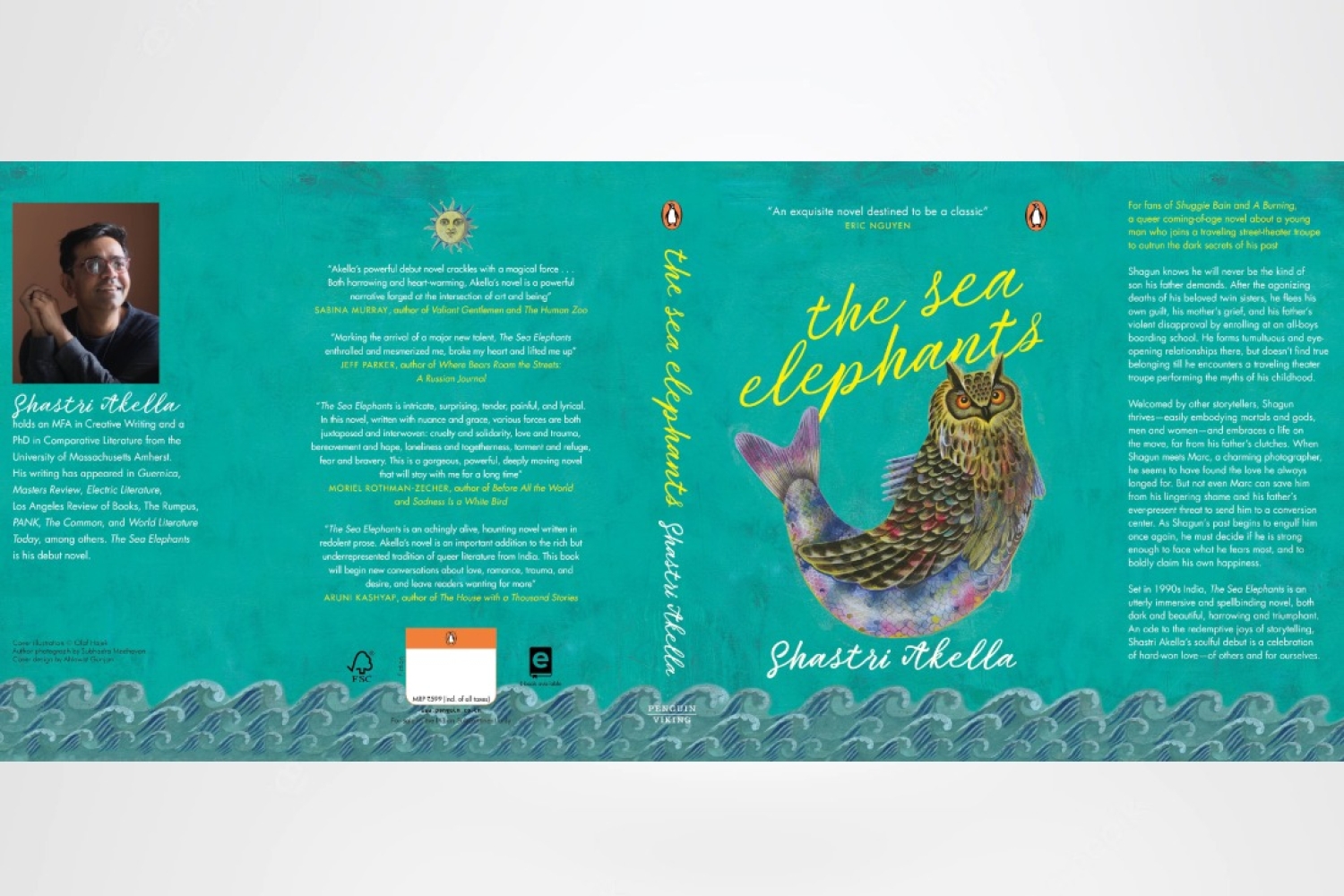

Of his movement towards writing his debut novel, The Sea Elephants, he further reveals, “Back then I assumed the urge came from the need to escape my reality. But now I see that I was, until then, drowning in the noise of expectations that we inherit from our social contexts and our families. And freed of that noise, I was able to listen to my inherent inclination for storytelling. I had grown up listening to the stories my grandmother would read to me or tell me. Listening to her is one my favourite childhood memories. It was she who told me about Iravat — the OG sea elephant!” The Sea Elephants is an exquisite novel. It is a story about the power of found family, storytelling, and the courage to show up for yourself and honor your essential truth, at the core of which “is a gay character who goes out into the world seeking platonic and romantic intimacy. He builds a found family, meets a man who loves him, and falls in love with himself.”

Read more from our conversation with debut novelist about the making of his enchanting book below:

What inspired The Sea Elephants, and what is at its core?

When I was trekking through Jageshwar, a specific image came to me. A young man in a seaside town is in his living room, transferring a framed photograph from the wall of the living to the wall of the dead. He turns and sees the wall of the living has only one picture left. It is surrounded by square-shaped stains. He locks his house and leaves. But where does he go? I came back to the ashram where I was renting out a room and started to journal about this man, whom I called Shagun, and wrote my way into a response to this question. He was out in the world, seeking platonic forms of intimacy. At the time, I thought I was asexual, so it made sense Shagun didn’t seek romantic love either. But where, I wondered, would he find this form of intimacy?

A few months later, I was in Hrishikesh. On my first evening there I got to see a street theater perform. They enacted the story of Chitrangada, a transgender character from, I was surprised to learn, The Mahabharata, censored out of the translations. The actors were not separated from their audience by a stage. They performed by the banks of the Ganga and we, the spectators, stood around them as they wailed, danced, and celebrated. I could hear their breath and smell them. At one point, one of the actors, a man dressed as a woman, met my gaze as he spoke, in the present tense, about war. I was moved by the nature of this intimacy between storytellers and their audience. After the performance ended, I asked them if I could join them for dinner. And over a plate of kachoris I told them I’d like to join them. I said I could write for them, relocating the myths into contemporary settings. The theater chief liked the idea but added that I must live with them and help with things like packing, loading, setting up tents. I agreed. We set a date and it was decided I would meet him in Uttarkashi.

I took a leave on loss of pay and and shadowed them for several months. That was how I got to make Shagun a street performer. And he finds platonic intimacy in the spaces that exist amongst storytellers and between performers and their audience. I came out after I joined the MFA creative writing program at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. And Shagun came out with me. His search for intimacy expanded to include romantic love.

Could you talk a little bit about the setting/context of the novel and what your creative process was like?

I was surprised to discover the number of queer characters in Hindu mythology and the plurality of its philosophy. Some of the current right-wing expressions of Hinduism we see are antithetical to the rich complexity of the source texts. So I knew that I wanted Shagun to perform these stories of characters who have been forgotten or erased from translations. Ironically, my search for contemporary queer fiction from South Asia was met with disappointment. Other than the writing of Neel Mukherjee and Rakesh Satyal, there was nothing I could find. By bringing up the queer myths into the novel, as stories that Shagun performs, I wanted to place The Sea Elephants in the lineage of our ancient myths, showing that the tradition of queer storytelling is in fact very ancient in India.

At the same time, I wanted the conservative ideologies that led to the censorship of these diverse cast of characters from our myths to be present in my novel as well. So Shagun joins a street theater troupe to escape homophobic institutional forces that you’ll read about it in the novel. Finally, I wanted Shagun’s love interest to be an outsider who is accepted by his family, so he serves as a foil to Shagun who is Indian but an outsider in his family. When I found the history of Jewish migrations to India, I decided that Marc, the boyfriend, would be American, his family relocating to Cochin to live in Jew Town, making India their new home.

Were there any influences, literary or otherwise, that guided your creation of this narrative?

I’ve read God of Small Things every year for my birthday for the last fifteen years so I get to celebrate with Estha and Rahel. Roy has influenced me both as a writer and as a thinker. She’s taught me how to write with both tenderness and brutality. I also love the writing of Namita Gokhale, Chitra Banerjee, and Aruni Kashyap — each of their stories has left on me a psychic thumbprint which informs my writing. When I joined the graduate program in the US, I discovered the deeply influential writing of Michael Chabon, Nicole Krauss, and Andrew Greer (who was recently at the Kolkata Book Fair!)

I admire the films of Mira Nair and Zoya Akhtar as well. While they’re very different filmmakers, both their films have a strong sense of place and show us how places shape people. Their films also have powerful wonder for life, no matter how hard life within the narrative reality is.

What kind of challenges did you face with this debut venture?

I came out in the process of writing this novel. In an early draft, Shagun was asexual and Marc is his friend. My creative writing professor at UMass Amherst read the pages of my manuscript and pointed to the subtext where it is clear that Shagun is in love with Marc. I took therapy, came out, and discarded my old draft and rewrote the story from scratch so queerness throbs through the whole narrative. That, I think, was the most challenging and the most satisfying part of writing this novel.

It did take me two years to find an agent for my book. An agent who initially looked at my book said that there’s no market for South Asian fiction in the US book market. And in 2014, I was told not to overemphasise the book’s queerness or it would not sell. I am glad I persisted and found a dream agent in Chris Clemans and dream editors in the Manasi Subramaniam (Penguin India) and Caroline Bleeke (Macmillan USA) who want to celebrate the book’s queerness.

What do you hope readers will take away from the book?

The decision about same-sex marriages in India will be out this July. But the debate surrounding it has been hard to read. I do think it is easier to hate in the void — when your hate is not grounded in individual narratives. When you get to meet and know people, though, there is the possibility to see them as individuals who are not that different from you.

So it is my hope that queer readers will resonate with the story, especially queer desi readers who don’t see ourselves in fiction. I hope liberal-minded straight readers will be strong allies and share this story, and everyone else will read it and see that we’re not all that different from everyone else and make room for us in social spaces — and see us as more than a threat to culture or as a source of comic relief.

How have you been coping with the pandemic, personally and as a writer?

In November 2021, during the heart of the pandemic, I lost my dad to Covid. He was in India, and I was in between visas, so I was not able to travel back for his funeral. I was a writing fellow at the Fine Arts Works Center in Provincetown, which is at the very tip of the state of Massachusetts. It feels like an island almost. Days after my dad’s death, a whale got beached on the shore of the town and died. I would often make the nearly one-hour long walk to go see the whale through its various stages of decomposition. And by the time I left, in May 2022, the whale was nothing more than skeletal remains. And in ways that I am yet to fully understand, that process of walking to go see the whale helped me heal my grief somewhat. The time in Provincetown did allow me to immerse myself in the writing of my next novel. The fact that it was far-removed from my immediate experience helped.

What are you working on next?

Here’s a quick IMDB-style summary: an Irish vampire and a Kashmiri doctor fall in love in New York in the near future where the white population is no longer the majority in the US.

Words Nidhi Verma

Date 28-07-2023