Anuja Dasgupta is a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores the intersections of nature, time, and memory through innovative, camera-less photography techniques. Specializing in anthotypes—a medium that uses plant-based photosensitive materials—Anuja creates ethereal, ever-changing images that engage with the natural environment in a deeply intimate way. Her practice emphasizes the impermanence of life, with her botanical prints gradually fading and evolving over time, mirroring the transient nature of both human and ecological existence. Drawing inspiration from her upbringing, cultural symbols, and the ecosystems she studies, Anuja’s work invites viewers to reconsider their relationship with the natural world, fostering a sense of interconnectedness and environmental consciousness.

Anuja Dasgupta (left) | Rangjon (right)

You describe your work as "camera-less photography," which is quite different from conventional photography. Could you explain what camera-less photography means and why you chose to work in this way?

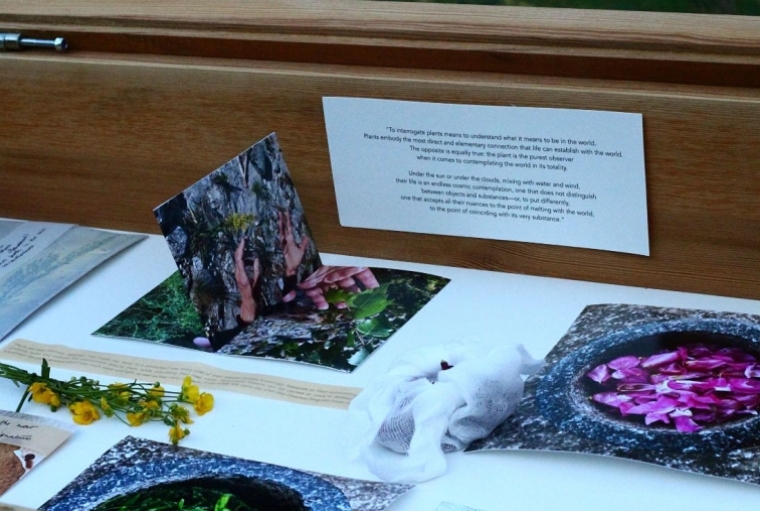

Camera-less photography is photography laid bare: light interacting with a light- sensitive surface. I work with a camera-less medium called an “anthotype” wherein the photosensitive material is made from plants. Unlike other camera-less photography techniques, an anthotype isn’t “fixed”, so these photographs continue to oxidise and fade with time.

It was a crucial juncture in my practice when I chose to make anthotypes. A photographer’s impulse is to freeze a moment in time, and as a photographer, I had started acting against it. Recording time was still my impulse, but not in moments. I wanted to embrace time. When I succeeded with my first anthotype sample in Ladakh with sea buckthorn berries, I knew I will be doing this for years to come. It is a slow yet deeply rewarding process.

In your project Elemental Whispers, you aim to push the boundaries of botanical imagery, moving from a surgical approach to a more contemplative and playful one. What was your creative process?

When I look at traditional documentation of plants, from botanical illustrations to photographs, I see a seizure of agency. These are often clinical, anatomical depictions to serve or echo scientific classification and examination. While valuable, these images remove plants from their eco-cultural context, reducing them to mere static specimens.

The 1000+ plants in Ladakh live many lives as food, medicines, ornaments, heat source and even bio-fencing, all while surviving extreme temperature variations. Their existence is entirely attuned to the climate which altogether shapes the regional fabric of life, yet they remain largely removed from discourses and creative practices in the trans-Himalayas. These learnings and realisations shaped my process for Elemental Whispers, where the river, wind, sunlight and fauna together make the anthotypes. Elemental Whispers is also a seasonal project as I work with found or cultivated plant material, which gives me a small window every summer to forage fresh leaves and flowers. The chromatic qualities of the floral photo-emulsions respond to the sun, while swaying with the river drift, making each ephemeral anthotype print unique.

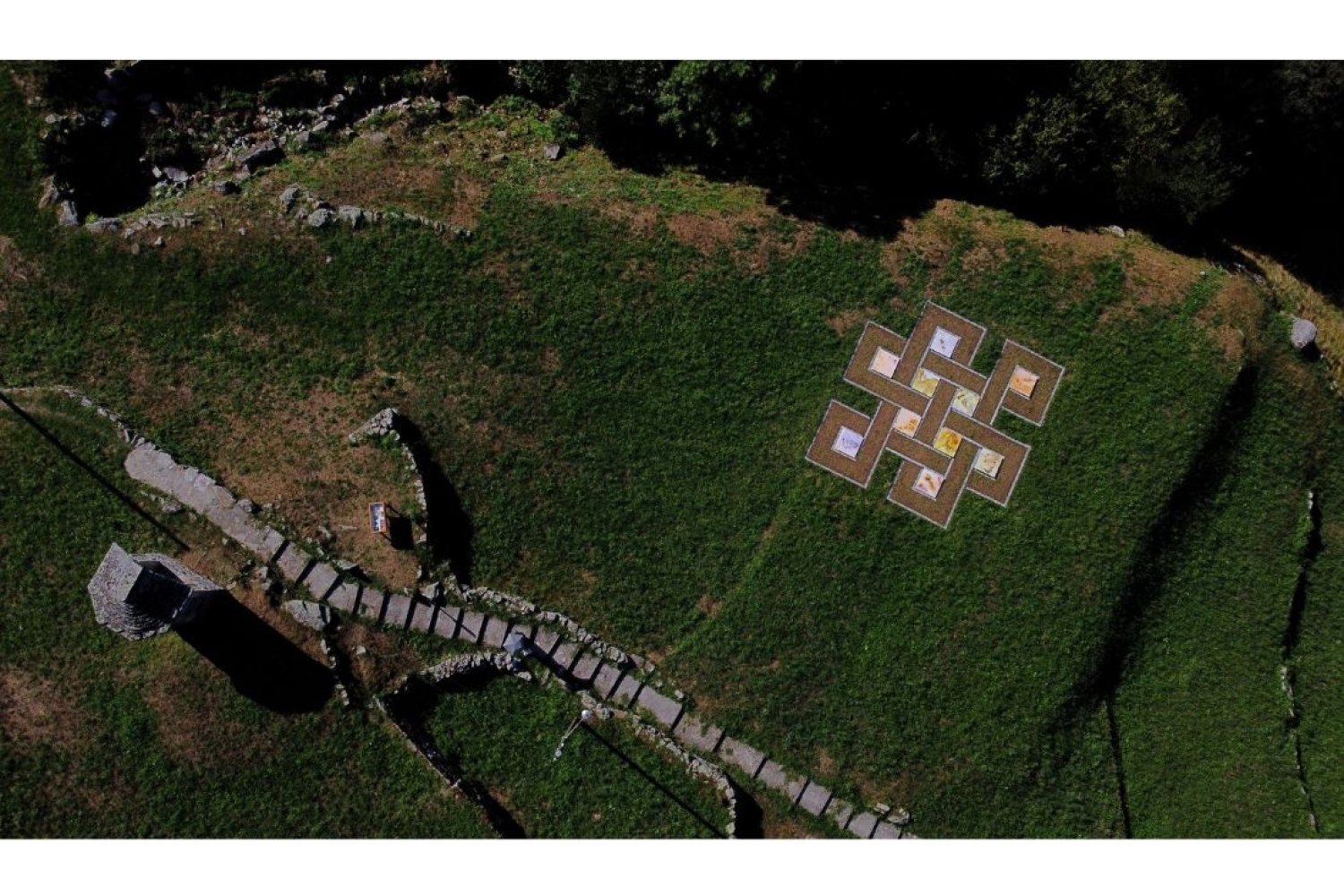

Your project in Switzerland, How Does a River Breathe?, explores the interconnectedness of natural ecosystems. Can you share how the concept of the “Endless Knot” came to you, and how you incorporated this idea into your photo-installation?

The Endless Knot is a symbol with which I have grown up. The eight auspicious symbols of Buddhism were central to my upbringing, and I still remember my father playing cassettes and DVDs of Tibetan incantations as if it were yesterday. These motifs and verses hold profound meanings, and I have been extremely fortunate to have been introduced to them at a very young age.

How Does a River Breathe? is another life of Elemental Whispers, in that it locates the river as an active site of interdependent relationships, and plants as nodes in this web of interdependence. Shortly after starting my residency in Verzasca, I discussed the Endless Knot with my curator, Alfio Tomassini. He urged me to make this central to my work, to share a glimpse of my ways of looking at the world to an audience far away from my own world. Upon creating anthotypes by River Verzasca and spending time in the valley with its people, I felt more strongly about the form of the Endless Knot. Such knots are common across religions and cultures, often denoting the interconnected essence of existence. I wanted the navigation of my exhibition space to evoke this essence, which would simultaneously be read with the prints on display with no beginning or end. Mowing the grass across 30 ft was no easy feat, but the incredible Verzasca Foto team made the installation come to life.

Elemental Whispers

Your work emphasizes the impermanence and fluidity of natural elements. How do you see your art contributing to larger conversations about environmental awareness and the relationship between humans and nature?

While in Elemental Whispers I work with the lesser-known flora of Ladakh, in Rangjon I work with the celebrated barren geomorphology of Ladakh. By and large, I intend to share a sense of wonder with my viewers—the same wonder I feel when I work with the rhythms of nature. Now to let this wonder lead to a conscious awareness of the trans-Himalayan ecosystem is something I leave up to my viewers. One way in which I try to unite these is through a small social enterprise I co-founded called Ladakh Orchards, where we promote traditional agricultural products and practices of Ladakh. That my stakeholders across my practices are the same—small farmers, traditional medicine practitioners, foragers—makes my own work holistic, which then makes it slightly easier to have the difficult conversations around environment and climate, and what we can all do in building a better future.

Looking ahead, what are some future projects or directions you're excited to explore, and how do you envision your practice evolving in the coming years?

My most recent exhibition titled (extra)terrestrial is an outcome of my residency in NIROX Sculpture Park, where I imagine the life of fire and frost adaptive plants in South Africa. This is an entirely new direction, as I move from a documentary approach to a speculative way of working with plants. We have such little visual access to the microscopic world where a singular existence is defined, regarded and reciprocated by another—a way of life we humans have completely sutured, and the many crises facing us today are only its repercussions. I feel the thread running across my practice will continue to be the notion of interconnectedness through different mediums. Perhaps a few decades from now, I will see this thread forming an Endless Knot!

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 04.12.2024