Chasers

Chasers

“Down, down, down. Would the fall never come to an end? ‘I wonder how many miles I’ve fallen by this time?’ [Alice] said aloud. ‘I must be getting somewhere near the centre of the earth... [or] shall I fall right through the earth?" - Lewis Carroll. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland: 150th Anniversary Edition (Princeton & Oxford: Princeton University Press): 8.

Encountering a strange creature - the White Rabbit, impeccably dressed with a pocket watch, but in a hurry - Lewis Carroll’s protagonist, Alice, follows him into a “large rabbit-hole under the hedge.” As she falls, Carroll conjures an otherworldly landscape underground, where perspectival realism collapses under the slightest point of stress; here, time slows down, spatial proportions twist askew, and the depths of the earth exhume distorted relics of modernity: Victorian cupboards, book-shelves, maps, pictures, and a jar of orange marmalade. This precise moment (and movement) - a free fall into the unfamiliar - becomes a simultaneous point of entry into (and exit from) Amitesh Shrivastava’s eerie, immersive, and luminous painterly compositions. Comprising six life-sized diptychs, Rabbit Hole maps a sensorial adventure: textured hues of blues, browns, and blood red obscure a potential source of light, a lingering abyss rendered visceral. But if one moves closer, these pixels saturate, and the image dissolves.

Familiar Path (Diptych)

Carroll’s novel resonated deeply with the Surrealist movement in the late 1910s, perceived through their raison d’e?tre: distortions of space, time, logic, and rationality. It isn’t coincidental that Salvador Dali - the noted archetype of surrealists - was commissioned to illustrate Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Random House in 1969. However, Shrivastava’s canvases reckon with a different, even opposite impulse: he doesn’t distort our visual field, rather, pierces into its very core, uncoiling the perceptual apparatus that negotiates meaning in our outer and inner worlds. The artist begins with a singular gesture, repetitively and laboriously weaving layers that move despite their stillness. Subjects and objects disappear and emerge, as the horizon - much like our psyche - remains unstable, inscrutable, and often, outside our line of control. Out here, Shrivastava reminds us that the seemingly disjointed visuals, or abstracted landscapes, are indeed, the closest to our lived experience of this ever-changing world - not the other way round. Rabbit Hole plunges viewers into corporeal depths, seen through the mirror of dense, macabre, and compelling artworks.

Flapping (Diptych)

Shrivastava continues to sidestep - with deliberate intent - any essentialist attempt to signify or categorise his art, for each work pulsates with “latent energy”, breathing and shuffling ceaselessly as you encounter it. What appears as a landscape, on a threshold, caught in the act of melting, upon a closer look, morphs into a gathering of figures. The Offerers speaks to the tenderness of an offering and the brutality of sacrifice; a man rushes to feed a goat, but in vain, for he reaches too late. His animal has been killed, and the fumes of a stove nearby subsumes their encounter - an unexpected agony, an ordinary day. As Ranjit Hoskote noted on the artist:

“Paintings such as these remind us of how robustly Shrivastava’s expressionist handling takes its place in the lineage that goes back to the turbulent dynamism of the Viennese master, Oskar Kokoschka. In Shrivastava as in Kokoschka, the artist’s dramatic personae are shown in the grip of extreme occasions that summon the self to action - variously to anguish, imperturbability, intimacy, and empathy.” 2

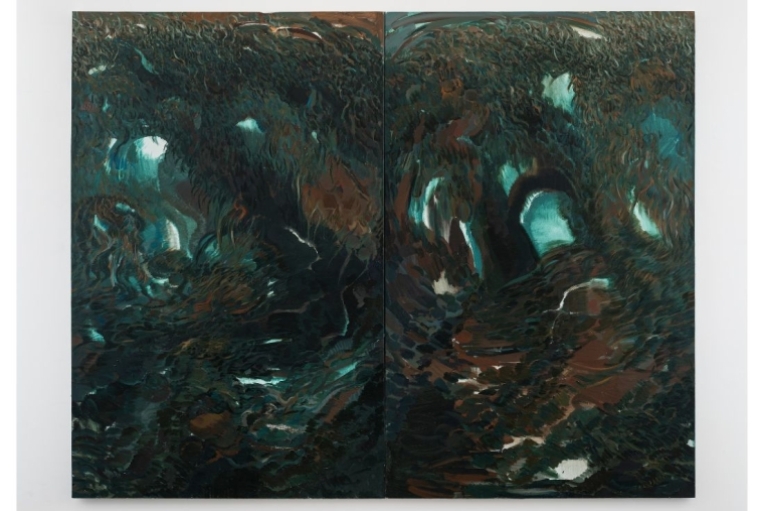

Rabbit Hole (Diptych)

Although he reckons between the tenuous relation between man and nature - as seen in his earlier exhibitions Counsellors (2020) and Trespassers and Translators (2017) - Shrivastava doesn’t romanticise the wilderness of rural fields, nor does he appeal to the anthropocentric discourse of urban spaces. Both animal and man appear vulnerable to their instincts, to their surroundings, and a looming mortality. Predator and prey are no longer fixed positions, but fluctuate, as the artist distils the immediacy of our senses - for instance, Feeling Brown, a striking diptych captivates your gaze in an instant. With earthy and foreboding hues, this vein-like orifice could also be its inverse - what appears as a colossal, tumultuous landscape in turmoil, could also be the interior of a narrow artery, capturing infinite sensations beneath our skin. Familiar Path holds two entities: a figure - evoking Sisyphus - that struggles to push a boulder, whilst another bird-like form, a seer perhaps, lies absolutely still, watching.

A nocturnal hue suffuses the next two diptychs: Twirling and Rabbit Hole. Bathed in the blues of the night, these works mark a subtle - yet poignant - shift in the artist’s oeuvre. Here, the human figure appears isolated (if at all) and caught threadbare, in a reflective haze, in between shifting lights and multiplying shadows. The horizon is on the move, in the midst of a quiet tornado, where linear time lies suspended. Slowly, the shadow expands into the waters, and is estranged from its own human self. Shrivastava alludes to the inscrutability - or contingency - inscribed not only in nature, but also in our own split psyche. As the man gazes into his reflection, one encounters “a seeing that doubts itself, and beyond that, doubts the world of man.” 3

Shrivastava empties these landscapes of the human, which at first, is unsettling. For what lurks behind the sublime, gnarled, branches in this forest? Could it be a predator, or our own hesitant shadow awaiting nightfall? Shrivastava further unravels this "eerie" sensation in his smaller Untitled paintings, where the absence of a figure is cast in sharper relief. Yet somehow, it is in these nocturnal works wherein the contradictions of our psyche come strongest to the fore. As the late cultural theorist Mark Fisher observed, it is “the eerie that allows us to see the inside from the perspective of the outside.”4

In Rabbit Hole, Shrivastava choreographs an analytic theory of vision: rethinking the sensorial apparatus complicit in our ways of seeing the world, and by extension, our own identity. The artist refracts - and shatters - our monochromatic or binary presuppositions, as the light splits into a spectrum of possibilities, emotions, and corporeal sensations. Out here, even the smallest encounter holds multitudes.

Words Sonali Bhagchandani

Date 26.11.2024