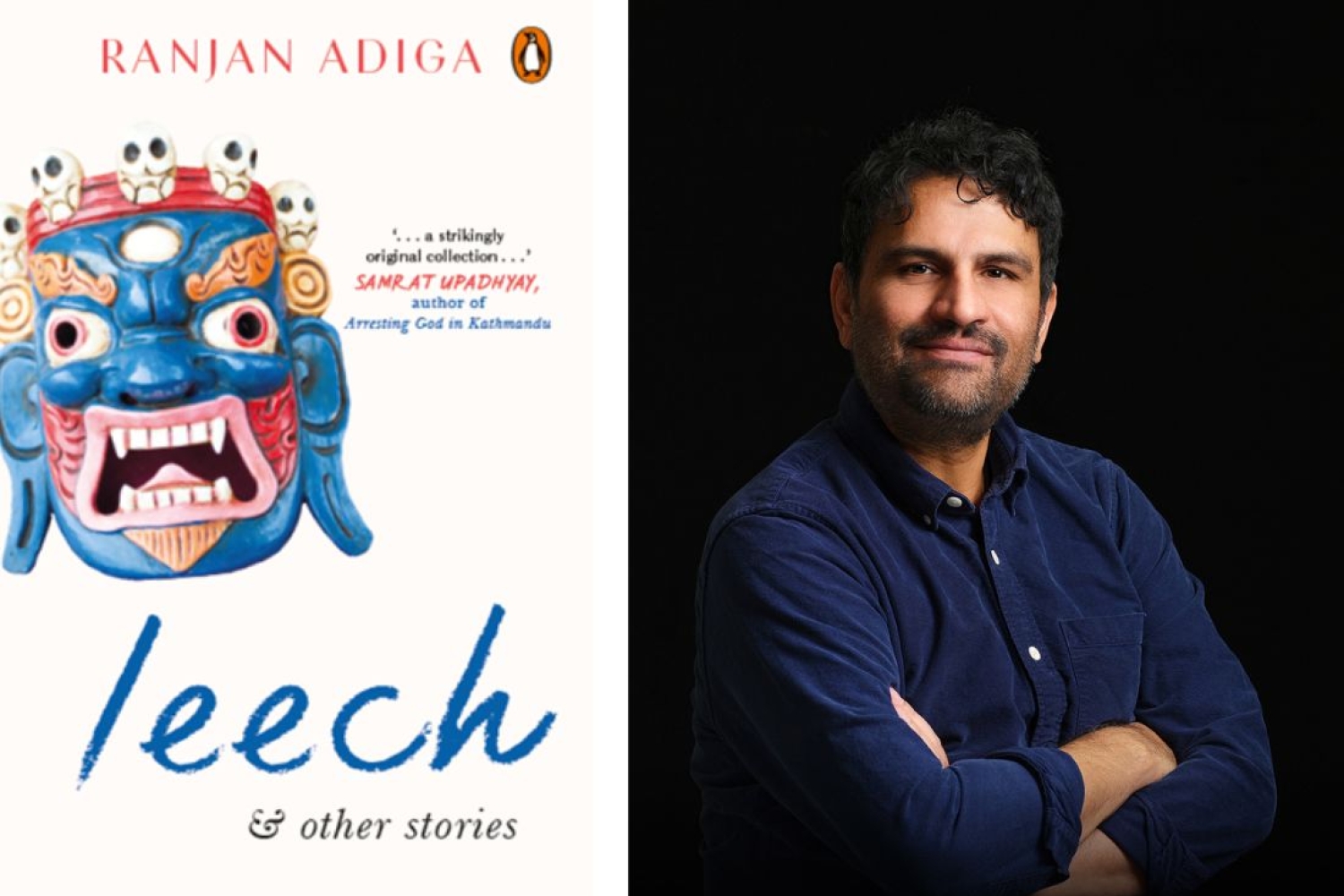

We rarely hear the perspective of the citizens of our neighbouring country, Nepal, in mainstream media. A country that is too close to our borders yet too far from the realm of our understanding. In an effort to bridge this gap and present Nepalis as multifaceted beings, Ranjan Adiga compiled 10 short stories about Nepalis and the diaspora in the form of the book, Leech and Other Stories. We talk to the author about his relationship with writing, Nepali stereotypes and their realities.

Tell us about your relationship with writing.

My sensibilities as a storyteller were formed in Kathmandu, a city of old temples and narrow alleys. When I was growing up in the early 90s, Nepal was ruled by a king, freedom of the press was nonexistent, and rumors and gossip had an easy sway over people. I grew up around uncles and grandmothers who were great storytellers. I learned about drama and cadence from them, but eventually, I was drawn to English books, movies, and music. Writing in English offered the promise of escape from those narrow alleys.

A lot of times, class forms the basis of various relationships. How do you think it affects Nepali society differently?

Class is omnipresent in Nepal. I grew up in a middle-class Kathmandu family. As is common in South Asia, we always had domestic help, a boy or a girl from the village who cooked, cleaned, went to school, and slept in a small room in our house. From a small age, I was made aware of class differences because I rubbed shoulders with a poorer person in the same house, but in the Jesuit school I went to, many of my classmates came from wealthier families who were dropped off in chauffeur-driven cars.

Our streets are not economically segregated like they are in the West. Step on to any Kathmandu street and you’ll encounter people from every social strata, coexisting, jostling for power in a world without maps. People’s lives can easily spill into each other’s. A gardener, for example, can have easy access into the lives of people they work for, and the madam of a house may have her guard down around her “servant” much more than she would around her own family members. Class is inevitably also linked with caste, so regardless of how class-fluid our society is, or may seem to appear, it is also entrenched in caste and class dogmas when it comes to relationships, marriage, and access to opportunities. In my stories, I like to crack open the fissures of those boundaries and imagine a world where classes and values constantly collide.

What made you delve into the urban politics of love within Nepali society and its diaspora?

I am interested in what is hidden under or beyond love, things that are left unspoken because of fear or insecurities. Whether that is between romantic partners, family members, or people we may encounter in our daily lives like barbers and work colleagues with whom we share a history of communication, silence, and miscommunication. My characters often seem to be trapped in a space of not knowing how to connect or belong, and their efforts to connect may be sad, absurd, or funny. Some of them are selfish and wonder what’s in it for me, while others are divided by societal issues like race, class, and language. We know that honesty, generosity, and humor are essential for love to flourish, yet so many people are dishonest and withhold their feelings about simple things. I’m interested in digging into those simple things as they accumulate into something dramatic and consequential.

In what ways does the format of short stories allow you to explore a diverse array of lives, and what significance does form hold in your storytelling?

One of my favorite writers is Bernard Malamud who had an extraordinary vision of the ordinary. His stories are sparse, but each one has the emotional volume of a novel. I love containing the challenges of character and plot in a shorter format, leaving it somewhat open ended, and moving on to the next story. Each story operates in a unique world, and I don’t like to overstay my welcome in any one story. Even though I wrote those stories, I feel like a guest in their worlds, and when I’m done with a story, I want to leave those characters to themselves, hoping that they will eventually find what they’re looking for. I would like my second book to be a novel, but I do think that I’m wired to be a story writer, because I’m more interested in ordinary encounters with lasting consequences than sweeping plot changes.

What do you hope for readers to take away from these stories?

I hope my stories present Nepalis as complex, multifaceted people trying to fight adversities in a complex world. I write about people marginalized by language, class, gender, and sexuality, and I ask the reader to imagine the ways in which we suffer and find hope through displacement. If that sounds too grim, my stories are also funny, I hope, and I see myself as an entertainer. I know Indians aren’t as obsessed with Nepal as Nepalis seem to be with India, but one always hopes that a book will find the readers it deserves. I hope readers find my stories entertaining and engaging!

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Date 30.05.2024