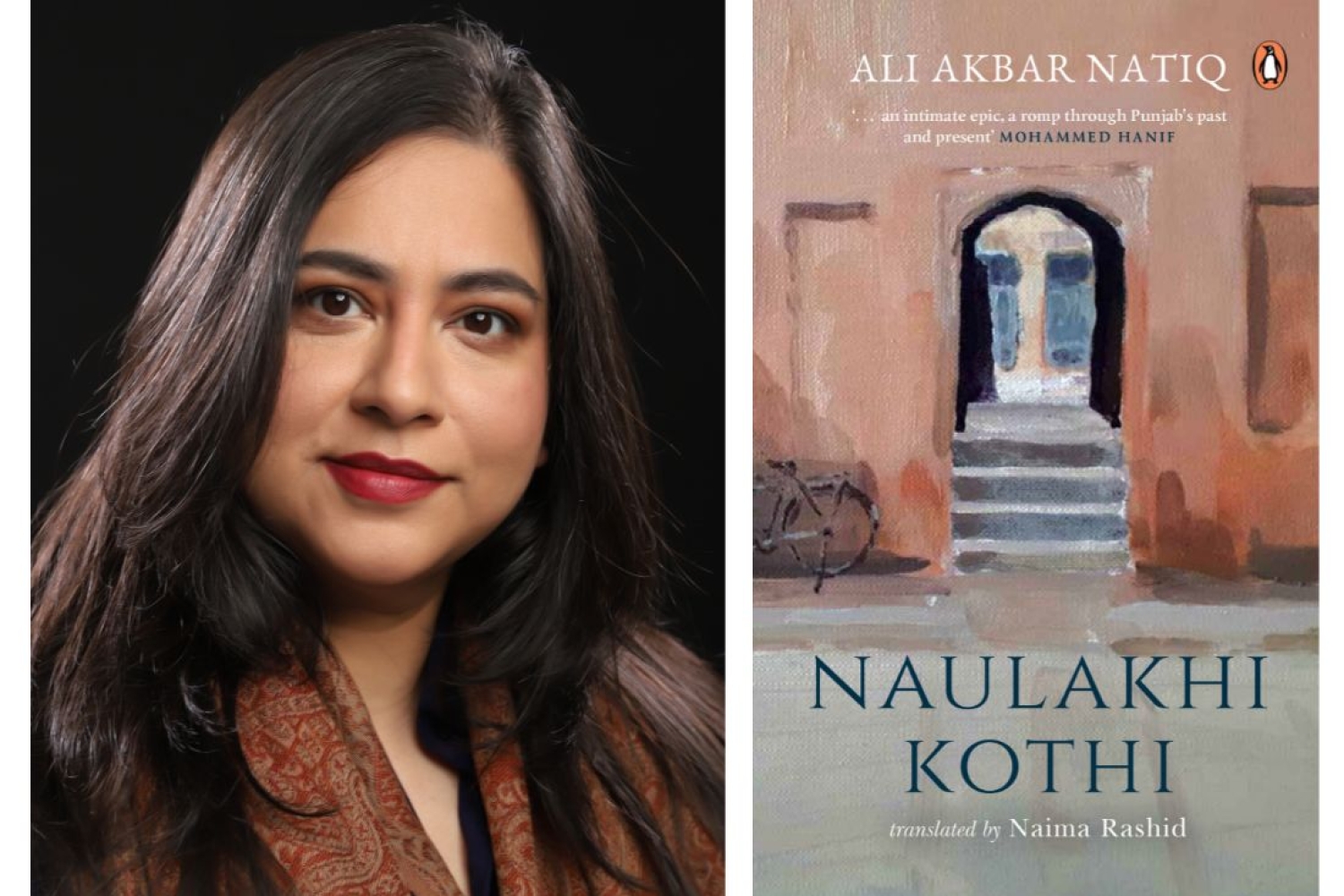

Naulakhi Kothi by Ali Akbar Natiq is a story set in pre-Partition Punjab, and revolves around William who returns from England to India after 8 years, and is appointed Assistant Commissioner of Jalalabad. The narrative is slowly built, and incorporated with a web of murder and mayhem throughout the plot. It’s a saga of a time bygone, filled with nostalgic memories, and the intricacies of feeling stuck in a place where you don’t belong. We’re in conversation with Naima Rashid, the translator of this novel.

What drew you to the art of translation?

I’ve spent my life living and working between languages and like many South Asian children, I grew up exposed to three or four languages in my household daily. It’s only natural that translation holds an irresistible appeal for me. I have to actively resist the urge to take on more translation projects so I can focus on my own writing, otherwise, I’ll never get any of my own books done.

How do you go about choosing the kind of work you translate – what is it about Naulakhi Kothi that made you want to translate the original into English?

First of all, the work has to speak to me. Naulakhi Kothi was about Punjab, my region, and its depiction of Punjab tugged at me strongly. Second, the project must represent a new challenge from the previous project. I had just finished a verse translation, Defiance of the Rose, with Oxford University Press and a collaborative translation of a feminist essay collection before, so a novel was a good departure from those two. Also, I am working on my own novel in parallel so translating a novel was instructive at the level of craft. It has made me more critical of my own process as a novelist.

The novel includes cultural nuances and contexts within Partition that might’ve been difficult to translate into English. How did you go about overcoming this?

I am an obsessive maniac when it comes to getting clear about things that I don’t understand at first, so I research a lot, I speak to as many people as I need to. Since the history of Partition is buried under layers of prejudiced recounting and intergenerational trauma which are only beginning to be unraveled, written accounts are often imperfect at best. Besides reading books, you have to speak to older people and look at their lived and remembered accounts to understand the meanings of things and get a sense of the way things were at the time.

Translation becomes a site for the possibility of a retelling and remains linked to the written text, but it doesn’t require fidelity to the written word. In that vein, what does your process of translation look like?

It doesn’t require fidelity to the written word, but it does require fidelity to the essence of the work which goes beyond the words on the page. It is a larger superset which includes tone, rhythm, silence, and nuance. The most important stage of translation for me is a close reading of the text. I spend a very long time at this stage, literally feeling the work in my bones. Then I begin drafting.

For poetry, the germination period is much longer, and the first drafts are almost final, needing little to no editing. For prose, I prefer to work with an imperfect first draft and finetune within it, spacing it out between editing rounds.

How has being in collaboration with other translators through your collective influenced your work?

Writing and translation are lonely tasks and translation is not an exact science, so it always feels like a delicate dance. Belonging to a community has many subliminal and practical benefits. From the possibility of getting real feedback and input on actual translation problems to feeling that your work matters. For Naulakhi Kothi, I had a session with the collective to workshop some initial hurdles and got to see their different approaches to translation problems specific to the project – translating proverbs, translating regional dialects and humour. As a collective, we look at translation through a practical problem-solution lens. The hive mind weighing in on each problem is a powerful resource to have at hand. I’m very grateful for that.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 18.10.2023