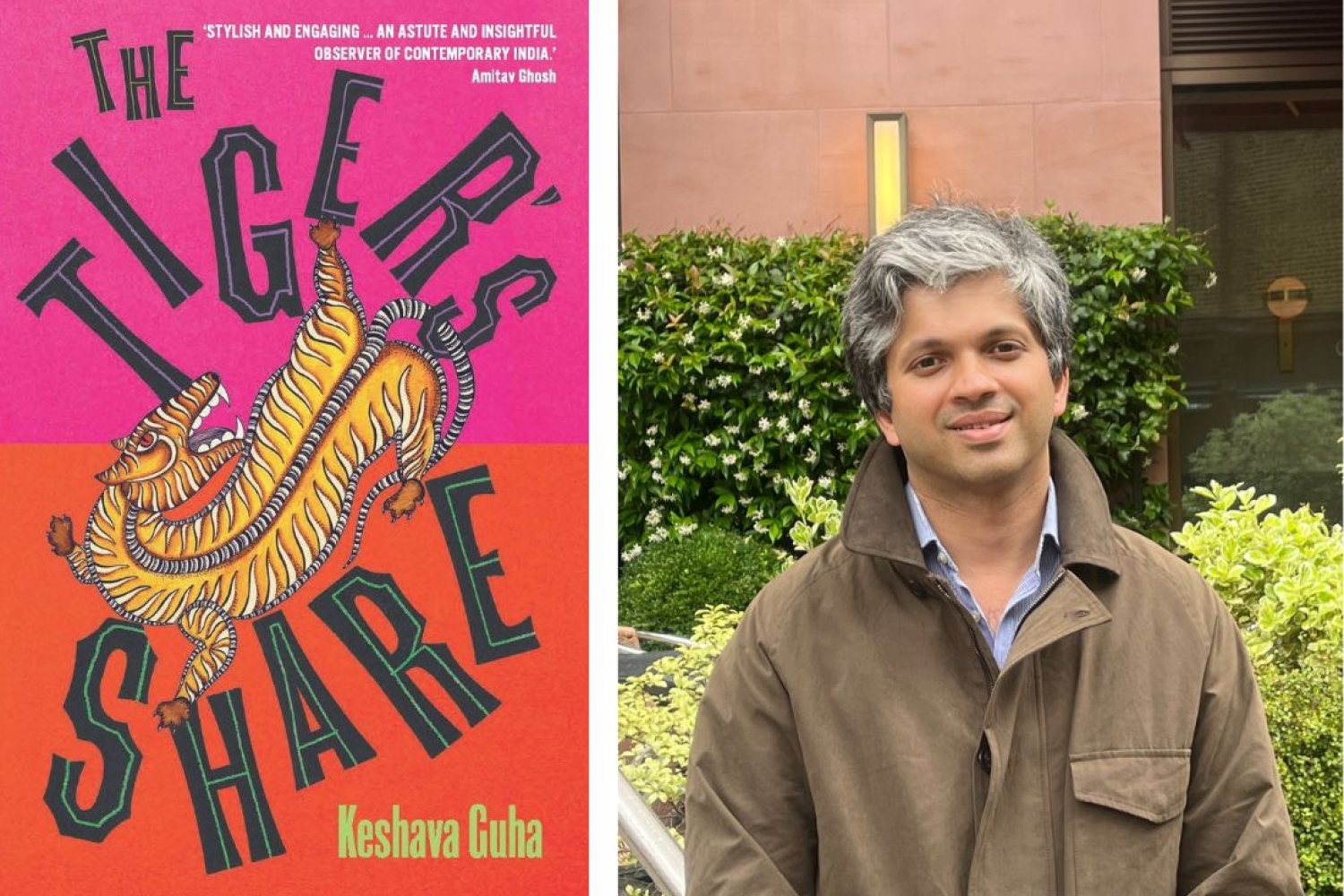

In The Tiger’s Share, published by Hachette India, Keshava Guha traverses a compelling narrative set in contemporary Delhi, carefully exploring family dynamics against the backdrop of political and ecological turmoil. The story follows Tara Saxena, a hardworking and successful lawyer, and her younger brother Rohit, who is aimless and unmoored. Their father causes disruption to their everyday lives by announcing his passion for India’s escalating environmental crisis, a decision that challenges traditional familial structures. Guha highlights generational rifts within the context of a patriarchal society and offers readers a nuanced perspective on duty, societal expectations, and the quest for personal and national redemption amidst environmental decay. We spoke to the author about his writing process, narratorial voice and the inspirations behind his new novel.

Since the book is set against the backdrop of ecological breakdown and political unrest, what aspects of contemporary India did you want to capture most in The Tiger’s Share?

The idea of the book began with Brahm Saxena’s ecological awakening. I don’t think it’s possible to write honestly about contemporary Delhi – or north India for that matter – without addressing ecological devastation (of which air pollution is only the most visible manifestation).

As that idea grew into a novel, the other social and political themes emerged from the characters. I would say that this is firmly a “post-liberalisation” novel, in that it deals with the changes to elite and middle-class urban Indian lives that the reforms of the 1990s unleashed – such as the growth of material ambition and a spirit of competition, challenges to established elites, as well as a scepticism towards older, nonmaterial values that powered the freedom struggle but were now seen by many as having held India back. And, of course, the rise of female ambition and its backlash, which is absolutely at the heart of the novel and drives much of the plot.

Tell us a little bit about how the broader themes of the novel intersect with the lives of Tara and Lila.

Early in the novel, Tara reflects on the many similarities between her and Lila and their situations and while, by the end of the book, the differences in their characters come to the fore, those similarities are still undeniable. Both were academically successful, and are now thriving professionals in traditionally male-dominated fields (law and investing); both are cosmopolitan, sophisticated, novel-reading. Both have younger brothers that resent them; and while Tara is committed to a life of her own, Lila’s marriage inverts or subverts traditional gender roles. Both, too, are much closer to their fathers than to their mothers, in part because their lives are so different from their mothers’. The differences that emerge between them illuminate another one of the book’s central themes: the battle between cynicism and idealism. I won’t spoil the plot by saying which character falls on which side of that divide, or how.

Since this novel is an attempt at preserving something “old-fashioned but of enduring value” – can you elaborate on how you balanced this classical approach with a modern, witty voice?

One of the distinctive things about the novel as an art form is that the seemingly old-fashioned can still be made fresh, because history and social change keep generating new material. It’s very different in that regard from painting, poetry or music, in which forms rapidly become outmoded. The form – the past-tense realist novel, conventionally punctuated and with a more-or-less linear narrative – is traditional, but the themes and the voice are contemporary, and the genius of the form is that it allows for that. If you tried, with modern Delhi as your subject, to paint like Ingres or compose like Schubert, the results would be absurd kitsch, but when one reads Stendhal, their contemporary, it’s amazing how adaptable his form is to our time.

Within the high stakes personal and societal conflicts that the characters face, how did you seamlessly braid comedy and tragedy together? What inspired this style?

The view that life is both tragic and comic is at the heart of everything I write and of most of my favourite novels. It’s not so much that comedy is a way of making life seem endurable – it’s that without it a portrayal of life is less than fully true. What binds the work of any writer together – whether they keep returning to the same themes or are always pursuing something new – is their sensibility. My own sensibility is ironic, and I don’t think there’s anything I can do about that. When I think about the contemporary writers I cherish most, all of them are both very serious and very funny – Roberto Bolaño, Helen DeWitt, Joseph O’Neill, and the poets Frederick Seidel and Nick Laird. Jai Arjun Singh wrote a wonderful book about the film Jaane Bhi Do Yaaro called Seriously Funny Since 1983 and I’ve always thought that was such a brilliant subtitle, because the thing about that movie, like so much great art, is that the funnier it is the more profound its insights into social iniquity.

What are some challenges you faced while writing this novel?

The greatest challenge, by far, was structural. As you know, the novel’s ending is highly dramatic, perhaps shocking. When I set out to write it, that shocking event – or at least the declaration that it was going to happen – took place right at the start of the book. I knew I had a strong idea but with every subsequent chapter the narrative seemed to become more strained. Eventually I put the book aside for a year and a half and eventually, while trying to write something completely different, I realised that what I had to do was shift this revelation to the end of the book. That opened everything up.

Tell us a little bit about what the future holds for you.

I’ve been working for two years on another novel, called The Conquest of Europe, that deals with another aspect of post-liberalisation India – namely the integration of India’s economy with the world’s. As was the case with The Tiger’s Share, figuring out the structure is a challenge that I’m still grappling with. And I’m about to move back to Bangalore, where I grew up.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 11.04.2025