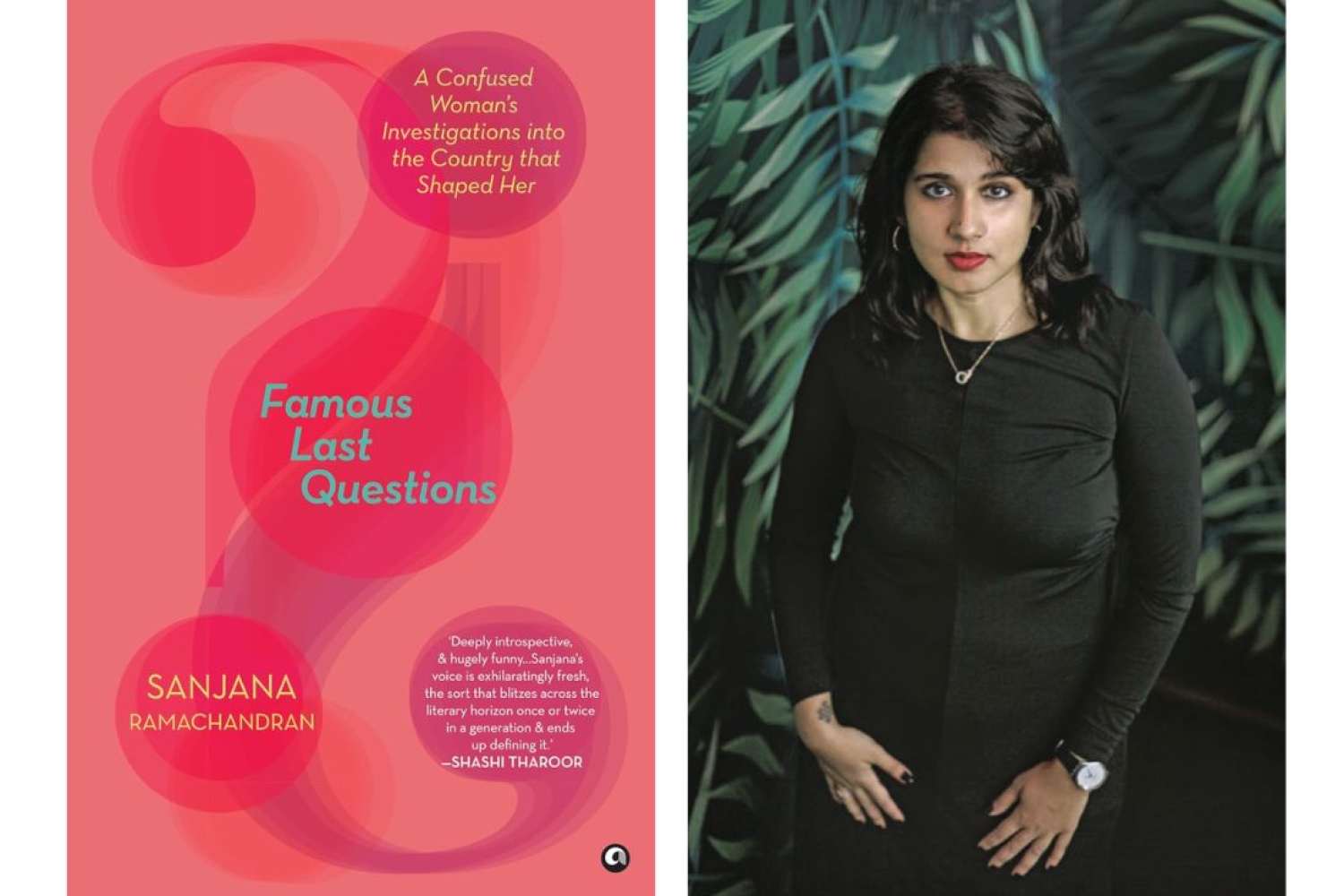

In her narrative non-fiction debut, Famous Last Questions, Sanjana Ramachandran invites us into a narrative that uses the deeply personal to answer questions about Indian society, particularly parental and cultural expectations. Starting with the 1990s until today, she explores how growing up in India with the internet affects the self, navigating multiple careers and personalities, hidden loves, gender, sexuality, and politics, which will resonate with anyone who has grappled with identity today, in a fragmented yet hyperconnected world.

Ahead of the book’s release, we spoke to Sanjana about how she navigates writing, research and ‘self-branding’ in the digital age.

Your book features personal experiences and observations about the people and institutions you’ve been a part of. How did you address any concerns about theirreactions to your writing?

I definitely had concerns and it isn’t just the book that draws from my experiences and daily observations. I’ve gotten into trouble for my tweets even and the underlying question thus is one that every artist faces: What do you owe the people, places, and relationships that inform your material? I’ve gone far to verify that I’m ‘meant’ to be a writer or comic or creative, as if to prove it’s not personal, that it’s not about anyone else or even me. And I’m glad to report that it doesn’t seem to be just for my ego that I’m making myself and others the butt of my material.

Another writer I turned to for answers was David Sedaris, whose personal essays are a huge inspiration. He says you’ve got to be emotionally honest in your writing, even if that means being hard on people. The only way out is being even harder on yourself. And I find that to be a fair standard. I hope readers of the book will see that its central journey is towards compassion even for those who have hurt you, not because we should be magnanimous or the bigger person, but because we have all made horrible mistakes—anyone alive has and people who don’t see that are perhaps insufficiently aware of themselves.

Then there are also creators who don’t think the burden of proving goodwill lies on you. Anne Lammott said, ‘You own everything that happened to you. Tell your stories. If people wanted you to write warmly about them, they should have behaved better’. And I believe this too. Any relative or ex of mine who feels badly about how I remember them can see how fondly I remember those I liked better.

So, the trade-off between relationships and honesty is for every artist to make and I think I’ve made mine consciously, with kind intentions, and I hope I can face any less-than-ideal consequences too. To know why this is beyond me, though, you’ll have to read the book.

Your book also discusses the challenges of self-branding on social media in today’s world. In what ways do you think self-branding has evolved over the decades?

We’ve come from the media being controlled by a select, powerful few before the ‘90s to everyone with a smartphone and internet access being able to tell their own story. Mostly, this is incredible advancement. We live in a golden age of artistry and freedom of expression, even if it’s come with a paradoxical rise in misinformation, trolling, mental health issues and everything else that proves that reality is not black-or-white, nor good-or-bad, but always a complex layering of both. Self-branding has that grayness in oodles, because on the one hand it is an outcome of finding your voice by producing lots of work and creating a market for yourself, architecting a life around potentially dis-parate, niche pursuits, which wasn’t pos- sible before. But, on the other hand, some of what it takes is also strange and dystopian: a kind of 24x7 on-demand productivity, constant consumption, which can confuse you about who ‘you’ are, and the quirki-fied, ‘chronically online’ packaging this takes, as if there aren’t real addictions and mental illnesses that go with it. There’s also an internalisation of the market’s view of the self, meaning you may want to edit yourself to maximise your appeal as others define it. But is that authentic or even art? There have always been artists who’ve pandered to an audience but I guess it feels a bit dystopian today because what sells is ‘authenticity’, but what you have is extreme performance and curation masquerading as natural. Then again, we’re always performing in our daily, social lives, with or without the internet; so I also think performance is also inherent to how humans are.

But as I write in the book, any Indian ‘being real’ online is likely risking judgment, or worse, from family, relatives, colleagues. Our performance isn’t always natural, in that we develop sub-selves for safety, depending on what is acceptable and to whom at any given moment. And when this compartmentalisation becomes extreme, the self too divided, it can become a form of identity-driven madness, which I explore in the book.

As a debut writer, what challenges did you face during the writing process?

It wasn’t the craft of writing or writer’s block or anything technical that bothered me most. Stories come to me and I’ve made them across formats now—ads, jokes, essays, screenplays, non-fiction, even presentations and graphs and technical writing are things you can call stories. But what’s been surprisingly challenging to reckon with is some thorny ideas of what it means to be a writer. I’m still investigating where mine come from but there are so many stereotypes: the writer as recluse, concerned only with word-string- ing and power-deconstructing, pure in their anti-establishment position with no ties to the establishment whatsoever. But as someone whose writing has been a response to being in and thinking about the establishment, I’ve always had one foot in it and one outside it.

I’m coming to see that as inevitable for any creator historically: it’s a long journey to making a living off of only your art and even then, some see value in other kinds of work, as I do. Does that make me less of a writer? I think the anxiety comes from how the world is constantly bucketing things: you’re either scientific or artistic, either creative or logical, either business-minded or true to yourself, either ethical or unethical. Maybe it also comes from the pedestal that writers are put upon and, when you finally become one, you realise how messy and un-glamorous it is. You’re like what was the fuss about? Journalists have written about the questionable methods and aims of their own profession. So, the more I traverse binaries, the less I see them as binaries: there’s a lot in common between disparate disciplines, and the ‘line between good and evil’ runs through everything. So, I want people and myself to see any lack of typical ‘writerliness’, if at all there is such a thing, as a strength, not a weakness. You can be greater than the sum of your parts.

Can you describe your research process? Your references range from Instagram posts and journalistic articles to philosophical essays and niche books.

They’re a cross-section of what I consume on the daily and where my curiosity leads me. My research process sounds basic when I spell it out like this but it’s basically Googling and being online a lot and connecting whatever I encounter to the questions and things I’m thinking about. The only research tip here that I think someone else might also benefit from is being unburdened by what anyone thinks is good or bad art or high-brow and low-brow. All information is fair game for consumption and to construct an argument or story from.

When you decided to tell your story, how did you recognise its connection to broader issues of caste, class and technology?

I start my book with the confession that it was the idea of telling stories about my life that kept me alive through many years, through many terrors. Earlier I would keep obsessing over what form the stories should take because you can connect a set of dots any number of ways. I continue to want to do all of them. I’ve written screenplays based on my life because film is so visual and dramatic and accessible, and it played to the whole my-life-is-the-movie-I-make-of-it myth. But in the creative spurt that followed the pandemic, I threw many things at the wall: these screenplays, yes, but also blogs and essays and articles. Some of my journalistic work really took off, so I continued to use that lens of analysis that had become familiar to me: Connecting my life to other people’s and the societal, cultural and technological shifts happening alongside. Reading a lot and compulsively coming at a subject from multiple angles: that is what a generalist brain with training in science and marketing and reading lots of good literature can get you.

Words Paridhi Badgotri

Photography Shreeya Bohra