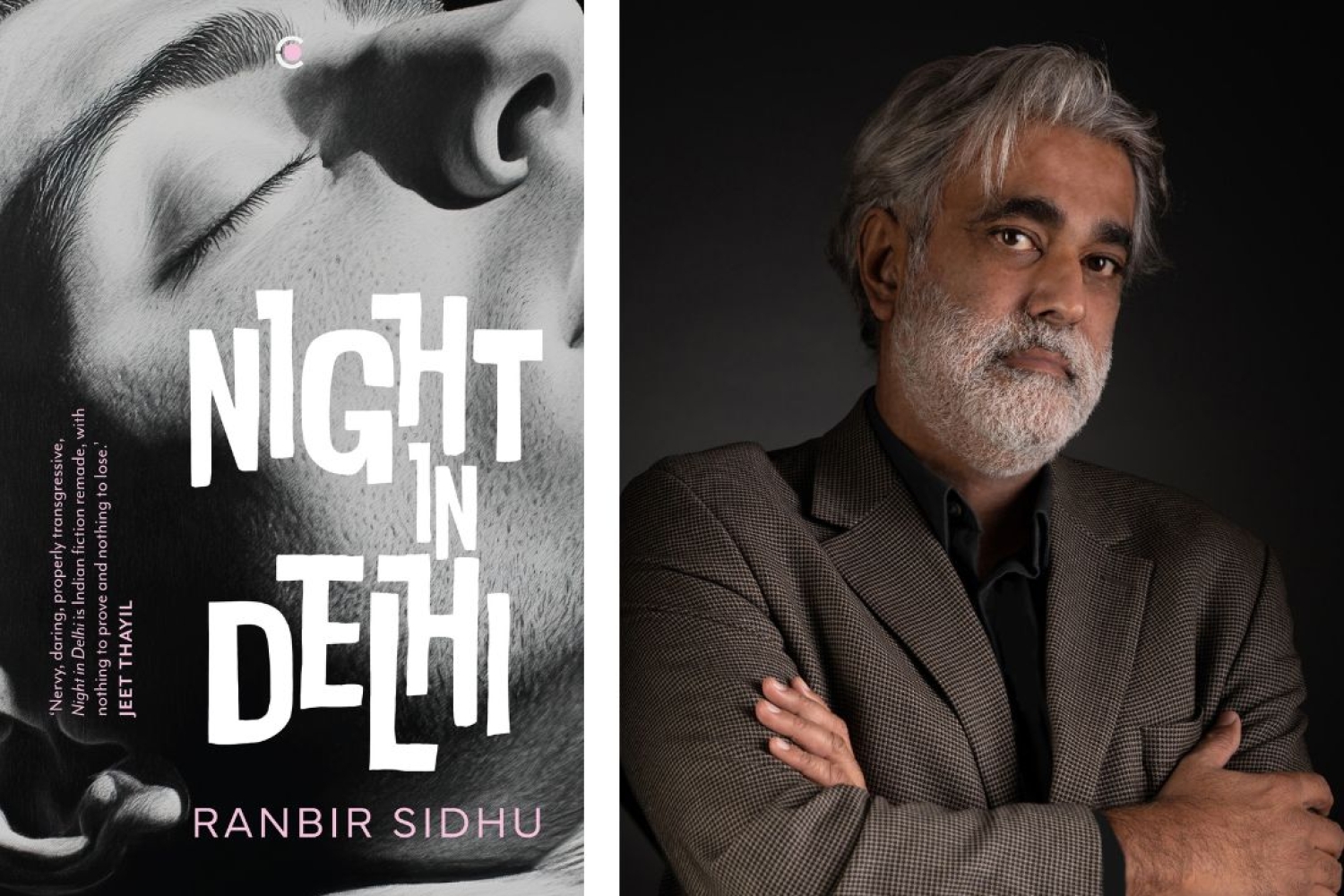

Night in Delhi by Ranbir Sidhu is a daring and transgressive exploration of Delhi's underworld, where moral boundaries blur and survival is a constant struggle. The story follows a thief, his lover-turned-pimp, a lost American, and a woman trying to rise within India's new mafias, all navigating a world of shades of grey. With sharp character development and dark twists, Sidhu's work blends fatalism with black humor, offering a gripping portrait of ambition and moral ambiguity. Praised for its intelligence and risk-taking, this novel is a fearless, thought-provoking read.

Read an exclusive excerpt below.

'A turbaned figure moves through the hall, a kirpan hanging from an age-battered belt, and distributes prasad from a metal bowl. I accept it, taking the warm, sticky sweet in my fingers, and bring my hands together in thanks and eat it quickly. Jaggi shakes my shoulder. It’s time to go to work, he whispers, but just then one of the old men, who is sitting near us, stands and walks stiffly over. A thin, straggly beard reaches down to the middle of his belly. He leans forward, holding himself upright with a cane, and tells us boys, as he calls us, that the langar has started, we should get something to eat. You didn’t know the dead man, he adds, I can tell, so what are you doing here? He means in the hall, there was no reason for us to show respect, they’d be happy to feed us either way. He doesn’t hide his irritation, scolding us for wasting our time on empty gestures when we should be filling our bellies. Come come, he demands. We rise and follow him. The musicians play. The old men are on their feet and children run in and out squealing.

The old man settles us down on a length of weathered carpet in the centre of the courtyard, a prime spot. Some women sitting opposite smile and nod in approval. A boy, maybe ten, appears with water, and is quickly followed by others, each bearing something different, dal, chole, sabzi, roti, dahi. The man distributing the roti is well-dressed, in his fifties, one of the sons of the dead man, performing seva for his father. After he drops a fresh roti onto my plate he pauses and stands there. You’ve read that? he says. He gestures to the book poking out of my trouser pocket with a nod of his head. I say yes and shrug my shoulders, as if to say sure but who cares. Find me later, he says, and moves on. The food was better last week, Jaggi whispers, this one just died of old age, there’s no shame in that. He calls over one of the boys for more sabzi and eats hungrily, while I haunt the crowd with my eyes, searching for bulging pockets, watches loose on wrists, phones or purses left unattended.

I finish eating and find the son of the dead man. He looks at me coldly. His shirt collar is frayed and flecks of roti cling to his jacket. The jacket looks off the rack and cheap, and he looks like he can afford much better. Prove it, he says without explanation. I ask him what he means and he says that I know what he means, and I do know, so I say, almost barking the words back at him, in English, You taught me language and my profit on it is that I know how to curse! He laughs and claps me on the back. So you didn’t just steal the Shakespeare, he says, and I say, Does it matter? He produces his wallet, a thick one, black and shiny, the leather frayed from age, like his collar, and pushes his card into my hand. Mr Harbans Singh Ahluwalia, Esq., embossed in gold. It shows an address in Karol Bagh. I’ll call you Caliban, he says, or is that your friend, and you’re Ariel. He nods across to Jaggi. He adds, It doesn’t matter, they were both just slaves.'

Date 13.01.2024