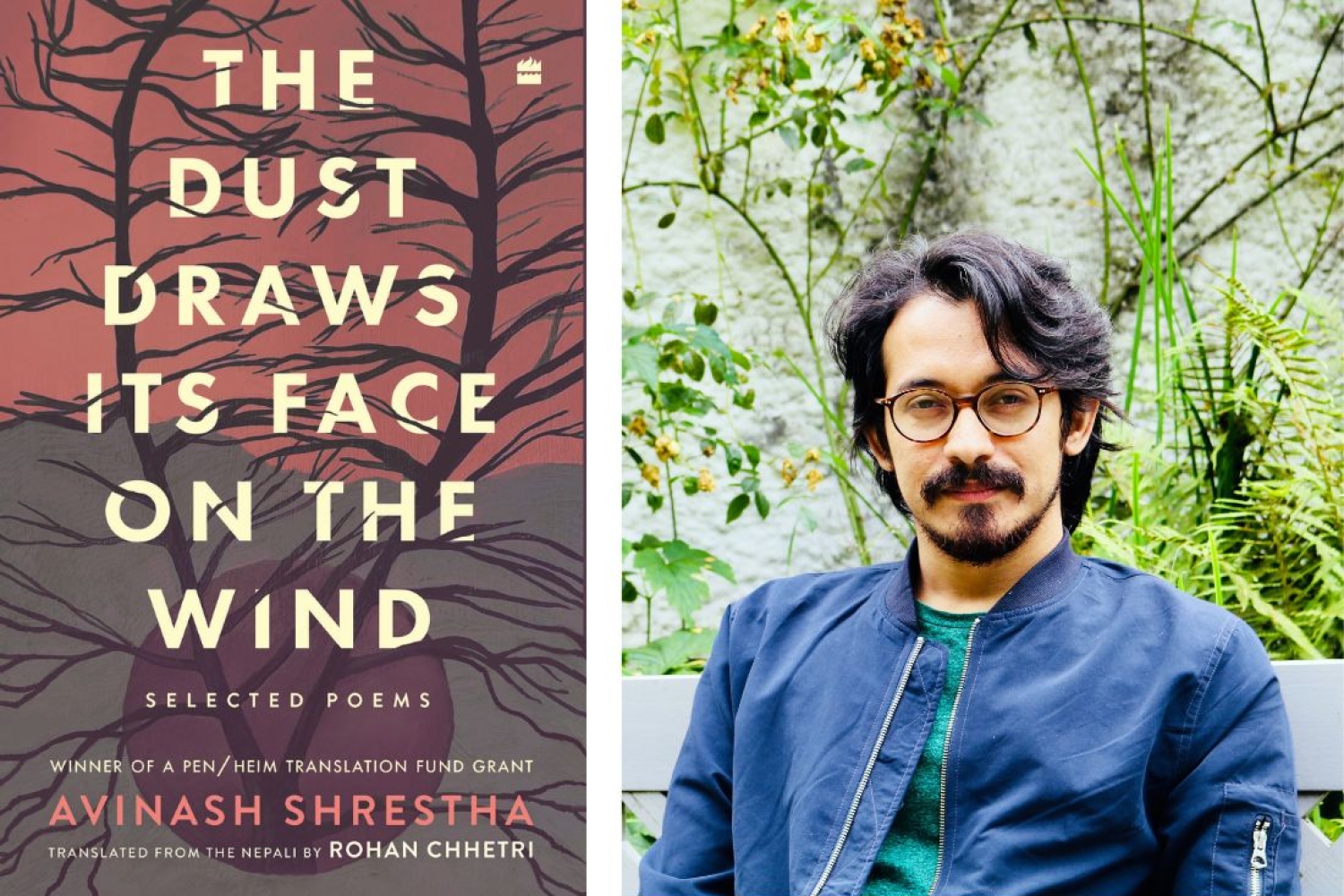

The Dust Draws Its Face On The Wind by Avinash Shreshta is the first collection of Nepali poetry available in English. We’re in conversation with Rohan Chhetri, who translated the collection, and elaborates on the translation process. He gives us insight into how he maintained the essence of the original work, and took on the role of a ‘negotiator’ between Nepali and English, resulting in a blending of culture, language, and context.

How did you approach the challenge of translating a blend of surrealism and modern Nepali diction, while preserving the essence of Avinash Shrestha’s original imagery?

Avinash Shrestha, when he moved from Guwahati, Assam to Kathmandu, Nepal as a young postgraduate student in 1984, wasn’t yet well versed with the contemporary poets in Nepal. His literary sensibility had been nourished instead by the Assamese, Bengali, Hindi and Urdu contemporary literary traditions. But he was also reading, by the late 70s and 80s, world poetry ranging from the French symbolist poets to the Spanish surrealist poet Federico GarciÌa Lorca, the Chilean poet Pablo Neruda and the Italian poet Salvatore Quasimodo, to American poets from Walt Whitman to Allen Ginsberg. While doing a Bachelor of Science degree in Guwahati, Assam in 1973–75, Shrestha also spent a significant time with classmates who were painters, poets and theater actors, and was made a co-opted member of the Guwahati Artists’ Guild, a meeting place for many prominent Assamese writers, artists and actors of the time. Watching these artists work closely, he saw in the language of visual arts the use of juxtaposition. In the early 1980s, at the height of the Assam Movement, ‘collage’ became a revolutionary idiom for the Nepali poets in Assam, and Avinash Shrestha spearheaded this Collage Movement in Nepali poetry.

Tracing his literary lineage by way of reading what he might’ve been reading when these poems were written was important to me, but it was also important for me to understand this lineage of the political undercurrent of the time that informs the avant garde impulse in Shrestha’s poetry. In many of his poems, Shrestha also seems to be consciously playing with vestiges of high Sanskritized ‘tatsam’ diction drawn from Assamese and Bengali poetry in India, which he uses to subvert and disrupt how Nepali poetry is traditionally expected to sound. He achieves this by his use of changing registers, alternating and mixing ‘high’ Sanskritized and ‘low’ folk diction, and also by using images and concepts from the Hindu liturgical tradition and Vedic cosmology, and finally, by pushing these against a surrealist, ‘deep image’ aesthetic that is modernist in impulse.

What was the most difficult poem or concept to translate, and how did you overcome that challenge?

There was no one poem or concept that was more difficult to translate than the rest. I was thinking of the translated text as a creative act in and of itself, a radical ‘afterlife’ of the original poem. This idea is contrary to the prevalent idea of translation as the transference of some ‘invariant’ from the original source language into the target language. I don’t think it is helpful to think of the translation of poetry in these merely functional terms, especially with the vast difference in the two languages at hand. I was more concerned with how I could allow the cadence and syntactic peculiarities of Nepali to infiltrate and contaminate the English, all in service of the unusual syntactic ‘order of disclosure’ and imagistic strangeness that is inherent in Shrestha’s poems. In the end, my work was that of a negotiator, to facilitate and contain this contentious meeting of the two languages and cultures in the translated text.

What drove you to translate this body of work?

I found Shrestha’s elliptical poems challenging and interesting linguistically, and their uncanny use of image and unpredictable metaphors were unlike anything I’d read in Nepali. When I began reading Anubhuti Yatrama (On a Journey through Intimations), his third book published in 1990, I had the first inkling of finally finding Nepali poems that, in translating into English, would take my own language elsewhere.

We’d love to hear about your journey as a translator - how did you enter this field? What are its best parts, what are some not-so-best parts?

I first started translating Avinash Shrestha’s poetry in an introductory translation class at Syracuse University in 2018. The year before, I had come across a small archival feature on him online from a 2003 issue of Nepali Times, with two of his poems translated by the writer Manjushree Thapa, who had noted that his work was ‘some of the most interior, emotionally charged poetry being written today by any male poet’. I procured an old copy of Anubhuti Yatrama (On a Journey through Intimations), his third book published in 1990, and began reading and soon translating from the book. The field was open. I soon realized I had no serious models. Beyond a few genuine but scattered efforts in anthologies and academic essays, no concerted effort had been made to translate a full-length collection by a contemporary Nepali poet, much less a retrospective on a poet’s selected works, and bring it to a larger anglophone audience. My foray into translation coincided with my PhD at University of Houston, where I engaged deeper with translation studies and the craft and the history of the discipline. I finally went on to earn a Certificate in Translation Studies alongside my doctoral degree. Attending Harvard’s Institute of World Literature conference during the pandemic and working with prominent translation theorists like Lawrence Venuti further cemented my deeper understanding of translation.

I love the sense of collaboration you feel you’re inherently a part of in the act of translation—the loneliness of the blank page is diminished. I don’t see the “not-so-best” parts if you’re really excited by the work, and to be excited you have to think of the translation of poetry as a creative act in and of itself, and as I said before, a radical ‘afterlife’ of the original poem. You better be excited by the work if you’re going to spend five years trying to possess yourself with someone else’s voice. Translation is an act of possession, in some ways, but like all true possession it is not a simple transference, the medium (or the translator) colors the manifestation of that possession to make it a third expression. My hope is that I have invented one discernible, recognizable voice in the translation of these poems. A voice that, although moves distinctly, metamorphosing through the stylistic evolution of Shrestha’s poetry, ultimately remains its own entity. A ‘collaborative’ voice, if you will, that has facilitated this meeting, yet neither claiming to be the author’s nor the translator’s, but a third—perhaps the fugal “Other” that appears in many of Shrestha’s poems.

Do you think the process of translating poetry is different from that of prose?

I do think there is a difference—poetry requires a heightened event of re-utterance and re-performance, of following the impulse preceding the original poem. Who knows that impulse better than poets themselves? I don’t mean to sound dismissive of the work of many scholars and translators doing very important work, but I believe, very strongly, in an ideal world poets alone can be trusted with the translation of poetry.

What is the future looking like?

I’ll be working on more translations from the Nepali—poetry and fiction—but for now this project is the first serious book-length "selected" poems volume of a contemporary Nepali poet into English, which I'm hoping will open a door for the rich tradition of Nepali poetry—while also introducing this long-unsung and important poet—to a wider anglophone audience.

Words Neeraja Srinivasan

Date 10.09.2024