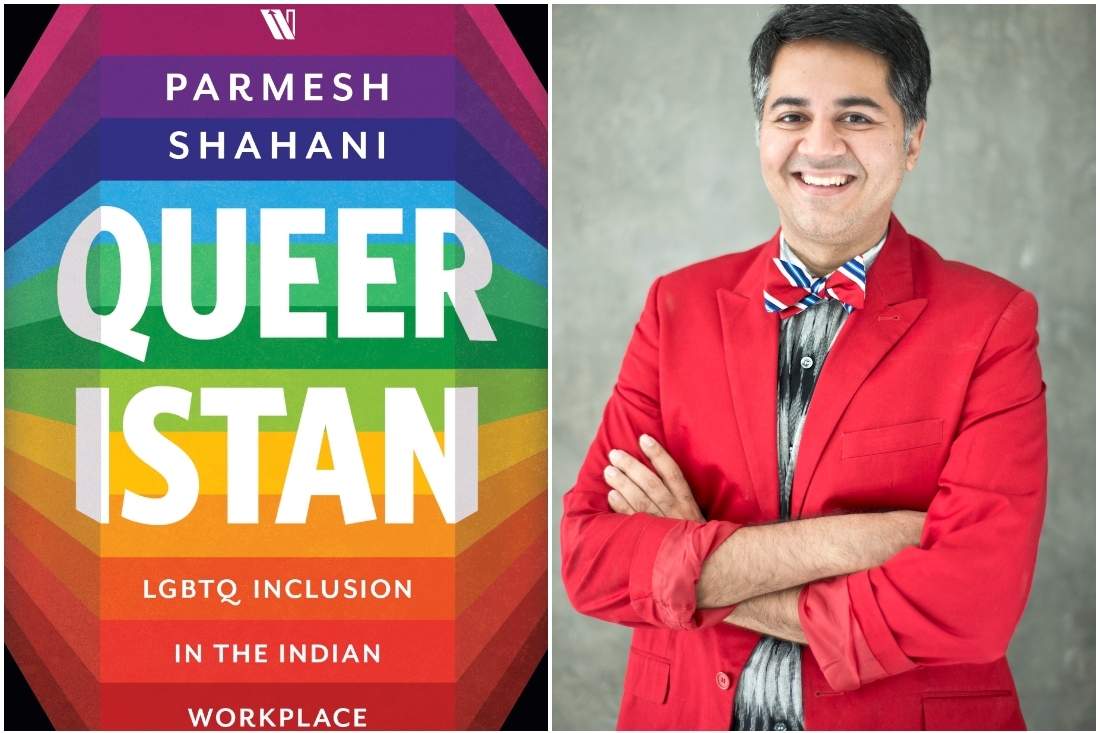

Before the writer/curator came a romantic/optimist. Parmesh Shahani has donned many hats and each with full heart, passion and enthused energy. He began his first job at the age of 19 and has been a part of the creative industry ever since. ‘I’ve worked for websites, I’ve been an entrepreneur, however not a very successful one! I’ve been a scholar at a place like MIT, where I studied and then helped run a think-tank for one year. Over the past decade, I've been in this strange hybrid space in the corporate world, running something like the Culture Lab for Godrej, but also using that position to talk about issues like LGBTQ inclusion. In the Culture Lab I have a team and we do events of different shapes and sizes. We invite people from various disciplines, and have an ongoing conversation and dialogue on the changing face of contemporary India. Also about gender, sexuality, what is urban and what is not, digitology, and environment. And after all that, I’m also a writer with two books. Professionally, I’m a hybrid.’

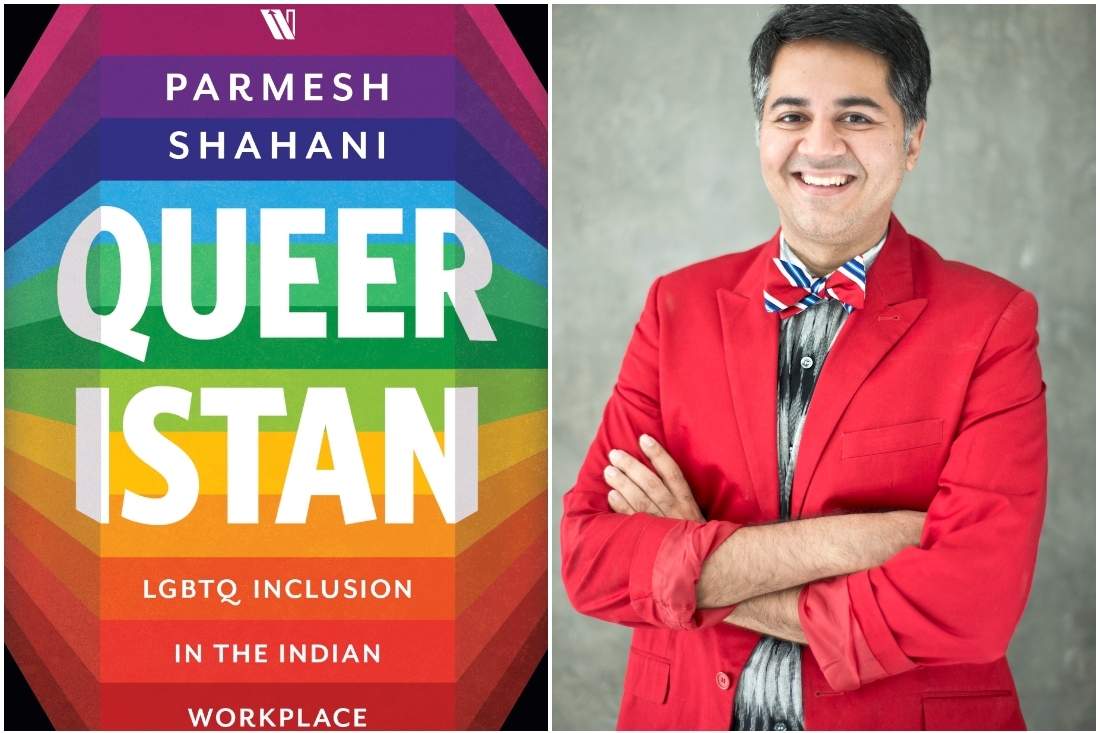

Queeristan, his latest exploration, like him, is hybrid. It’s a memoir and a manifesto. ‘It’s Hema Malini meets Homi Bhabha.’ When one reads it, instantly one is intrigued, as was I. I connected with the very interesting, positive and focused Parmesh to know more about his story.

Living in the hyphen

I love fashion, I love design, I love colours. I love art. Retrospectively and retroactively I define myself as a curator. When I think of the way events are curated and books are written, in that sense my journey is also a curatorial one. Making connections between unexpected things, that's what a good curator does. Homi Bhabha wrote about living in the hyphen, and I think that’s what I do. I live in the in-between state.

First Job. First Impression.

My first job was when I was 19 years old, working at Times of India, under Bachi Karkaria who is a legend. My immediate boss was Shashi Baliga. My world view has been highly shaped by my first job. It was 1996 and I was a college student at the time. There was a newspaper called the Metropolis. I didn't like one particular weekend edition so I walked into their office, somehow I got access and I was in front of these two editors. They asked me about what I did and then said, ‘you’ve come here to give us feedback, but do you want to help us make it a better newspaper?’ So I said okay, and they offered me a job immediately, which was incredible!

They took a call on this brash, inexperienced person simply because I had made an effort to go there. They gave me the youth section to handle. I asked them later, ‘Why did you hire me?’ and they said, ‘We thought you had the right attitude and skills can be taught.’ Hence, through the years, I've always tried to create opportunities for young people — nurture them and help in their growth, through the Culture Lab and the other things I’ve done. Similarly, when I went to MIT and worked under the tutelage of Professor Henry Jenkins, again an academic legend, I found that same kind of nurturing spirit which empowers people.

Queeristan

I framed it as an imaginary place, but also a real place, which we are co-creating around us everyday. It's a society — our society. It's just a way of looking at an inclusive Indian society, and Queeristan the term I affectionately use for it. The last section of the book talks about how we’re already co-creating this society. I talk about not just accepting parents but accepting colleges, how politicians are beginning to stand up for LGBTQ rights, and the changes in the Law. Also about how particular states are more progressive, whether it is Kerala or Chhattisgarh, or even Maharashtra, which recently instated a trans-welfare board. So at the end of the book, I sort of list out all the changes that are happening out there and we’re already in the beginning stages of creating this progressive inclusive state. Now the onus is on all of us, to help co-create it further.

Your Voice

I really want to create a more inclusive world for all my friends and colleagues, who did not have the same kind of privileges that I did. Over the past ten years, with the work that I have done and the people I’ve met, it's made me realise how a lot of work that I want to do in the future is about building infrastructures of equality at a systematic level. Because in my life, whatever happened was exceptional. It is not to say that I have not been discriminated against. I have been bullied when I was young. One faces micro-aggression all the time. When you grow up against a norm, whatever that might be, there is discrimination. But in my case, there was less discrimination than other people have faced.

So, a lot of the stories in the book are actually optimistic stories. I wanted to write with a framework and viewpoint of optimism. There are enough stories on the news about harassment of LGBTQ people, suicides and parents forcing their children to convert. There’s a lot of bad stuff happening in our country, all the time, not just related to LGBTQ community. I wanted to showcase the range of good things happening as well — accepting parents, accepting workplaces, incredible LGBTQ community groups that are forming across the world. My point is, to create a better world, we need hope. And we can find hope in these small, multiple acts of change that are also occurring. I want people who read the book, to be charged with enthusiasm that they can imagine a better tomorrow.

The Reader

Because I’m located now within the corporate world, and because the book is a business book, I knew my desired target audience very well. I wanted HR managers and MBA students. My primary target audience are influencers, because if I can create in them an understanding of inclusion in general and LGBTQ inclusion in particular, I can also show them the steps on how to practice it. Then fundamentally, they can bring up the changes in the organisations that they are in. But as I began writing, I realised that I want to write a business book that really moves. Data, statistics and case studies are useful, but they are not moving, they don’t touch the heart like stories do. Also, over the past ten years I’ve met incredible individuals, and all their stories are in the book. I also realised the importance of my own journey — this person who grew up in Colaba, who went to a seven-rupees school, and then on this surreal journey around the world. I felt that it might be useful to connect my own journey and talk in the book about how because I’ve had parents who’ve accepted me and organisations that have helped me flourish, it empowered me deeply.

I want business people to read Queeristan, and say oh my god, this is interesting! I want them to be invested in the narrative. It’s an argument — I want to convince people that when you include queer people, everyone lives.

The Changes

Every company needs to have comprehensive policies that protect their LGBTQ employees. By comprehensive I mean policies that have various specific norms on discrimination, that have same-sex partnership benefits, and provision for gender affirmation surgeries for any trans employees who may wish to transition. Also, an inclusive workplace must work very hard on sensitisation of its existing employees, because there is still a lot of bias, whether it is during workshops or around round tables. So there should be active sensitisation programs at every level, helping employees understand why the company is venturing on this inclusion journey. It should not just exist at a policy level, but translate into real behavioural changes.

Lastly, the company should really reach out to and support LGBTQ community efforts in their respective cities. In every city now, there are incredible LGBTQ organisations, and it would really help if companies are supportive either through CSR or any other way. It is important that the queer community understands that you really care. In this way, you’re sending a message to the community that your issues matter to us.

Text Shruti Kapur Malhotra